The Bard and the Troubadour

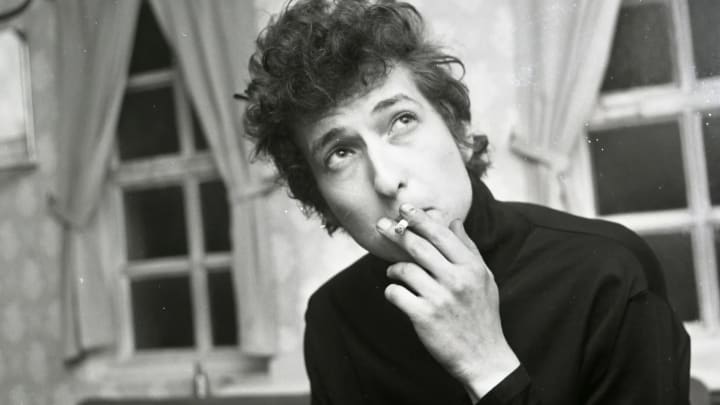

William Shakespeare's Influence Upon the Works of Bob Dylan

Background and Context:

I am back again with all these random notes from university (a long way back now) being turned into essays finally. You might ask me why I'm doing it now and really it's because I've been looking at them lying around for a long time now. There's many in my bank at this point and I like to think writing them now is doing them a little bit more justice than writing them back then with my less apt writing skills. However, there's always room for improvement. If you go on to my page and have a click around, you should be able to find a whole host of essays.

The Bard and the Troubadour

William Shakespeare's Influence Upon the Works of Bob Dylan

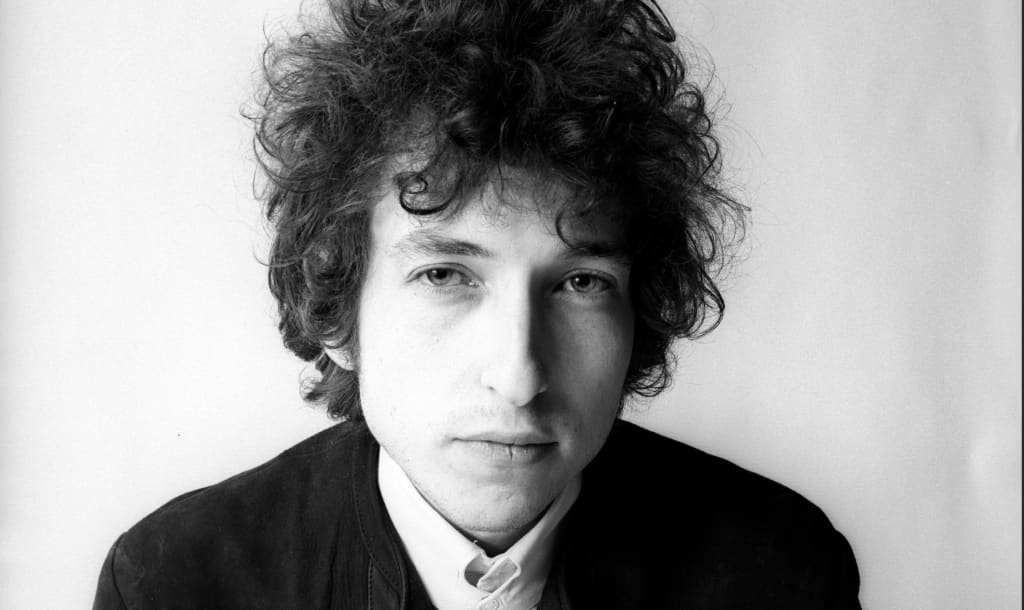

Bob Dylan is regarded as one of the most influential songwriters of the all time, blending folk traditions with literary depth. His lyrics have long been recognised for their intertextuality, drawing on religious, historical, and literary sources, including the works of William Shakespeare. As Christopher Ricks argues, Dylan’s writing is “a literary achievement on a par with the greatest poets of the English language” (Ricks, 2003). This positions him within a broader tradition of lyricists engaging with canonical texts, particularly those of Shakespeare, whose influence pervades both high and popular culture.

Shakespeare’s language, themes, and character archetypes have shaped literature and performance for over four centuries, and his presence in Dylan’s songwriting is both direct and implicit. Critics such as Richard Thomas (2017) have highlighted Dylan’s use of Shakespearean allusions and rhetorical techniques, noting that his lyrics often echo the Bard’s preoccupation with fate, betrayal, and the passage of time. Dylan himself has acknowledged Shakespeare’s impact, referencing Hamlet in Po’ Boy and drawing upon the dramatic irony and moral ambiguity found in plays such as Macbeth and King Lear (Thomas, 2017).

This article explores how Dylan engages with Shakespearean language, themes, and storytelling, not merely through explicit references but through a shared sensibility. By examining his lyrics, structure, and narrative techniques, we can uncover the ways in which Dylan, like Shakespeare, crafts enduring works that resonate across generations.

Traces of Shakespeare

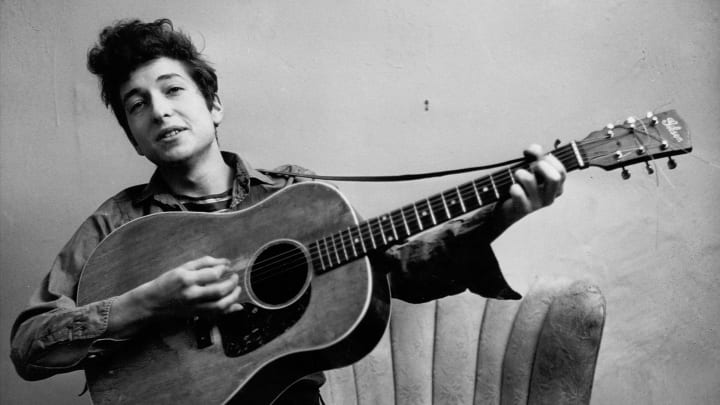

Bob Dylan’s engagement with Shakespeare extends beyond explicit references; it manifests in his approach to storytelling, characterisation, and linguistic style. Both figures are masterful in their use of dramatic structure, shifting perspectives, and richly drawn archetypes. As Ricks (2003) notes, Dylan’s lyrical depth places him in a lineage of literary greats, and Shakespeare’s imprint can be seen in his songs’ themes, narrative techniques, and poetic cadences.

Dylan’s ballads often function as miniature plays, weaving together deception, intrigue, and moral ambiguity in a manner akin to Shakespearean drama. Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts (1975) is a prime example. Much like a Shakespearean history or tragedy, the song unfolds through multiple perspectives, shifting between characters as they navigate a world of love, betrayal, and violence. The song’s theatricality, featuring secret plots, hidden motives, and an ambiguous resolution, mirrors the narrative complexity of Shakespeare’s plays such as Hamlet or Othello, where truth is obscured by layers of deception. Thomas (2017) argues that Dylan’s ability to “construct an immersive, multi-voiced drama” draws directly from Shakespeare’s storytelling techniques.

Dylan’s lyrics frequently invoke archetypes that align with Shakespearean figures, from tragic heroes to fools and ghosts. In Po’ Boy (2001), Dylan alludes to Hamlet with the line, “The ghost of our old love has not gone away,” evoking the spectral presence of Hamlet’s father. The song’s protagonist, caught in a world of illusion and misfortune, resembles Shakespearean figures struggling with fate and personal downfall. Similarly, All Along the Watchtower (1967) presents cryptic, prophetic figures (the joker and the thief) who embody the wisdom of Shakespearean fools, characters who often reveal uncomfortable truths (Thomas, 2017). The song’s apocalyptic tone and circular narrative recall the storm-ravaged, visionary world of King Lear, where chaos reigns and the line between madness and insight is blurred.

Dylan’s fascination with doomed, wandering figures also finds echoes in Shakespearean tragedy. Desolation Row (1965), with its grotesque parade of outcasts and misfits, recalls the existential despair of Macbeth and the moral disarray of Timon of Athens. As Barker (2018) observes, Dylan, like Shakespeare, populates his work with figures who reflect society’s anxieties and contradictions, presenting them through poetic yet unsentimental storytelling.

While Dylan does not imitate Shakespeare’s verse, his lyrics occasionally echo the cadence and rhetorical flourishes of Elizabethan drama. Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands (1966) demonstrates a formal, incantatory quality reminiscent of Shakespearean soliloquies. Its extended verses, rich in imagery and repetition, evoke the poetic grandeur found in Romeo and Juliet’s declarations of love or Hamlet’s introspections. Ricks (2003, p. 278) argues that Dylan’s use of elongated phrasing, alliteration, and rhetorical balance “aligns him with the most enduring traditions of English poetic form.”

Furthermore, Dylan’s playful manipulation of language, his use of paradox, irony, and archaic phrasing, suggests an affinity with Shakespeare’s linguistic inventiveness. In Highlands (1997), Dylan’s surreal, meandering dialogue between the speaker and a waitress recalls the witty verbal sparring found in Much Ado About Nothing or Twelfth Night, where language becomes a game of power and evasion. Such moments reveal Dylan’s Shakespearean ability to capture the nuances of speech and character within poetic form.

Dylan’s engagement with Shakespeare is not confined to direct quotation but is embedded in the very fabric of his songwriting. From his intricate narratives and multi-dimensional characters to his echoes of Shakespearean rhythm and rhetoric, Dylan’s work reveals a deep, intertextual dialogue with the Bard. As Thomas (2017) suggests, both artists “operate at the intersection of poetry and performance, using language to create worlds that remain endlessly open to interpretation.” This interplay between song and stage, lyric and drama, affirms Dylan’s place within the same literary tradition that Shakespeare helped to define.

Shared Themes

Bob Dylan and William Shakespeare both explore timeless themes that continue to resonate across generations. Their works interrogate fate and free will, love and betrayal, and power and corruption, core concerns of human nature and society. While Shakespeare dramatises these themes in plays filled with political intrigue, tragic downfalls, and psychological complexity, Dylan reinterprets them through poetic lyricism, often embedding similar conflicts and philosophical dilemmas within his songs. As Thomas (2017) notes, Dylan’s thematic range “mirrors the breadth of Shakespearean drama, from the deeply personal to the overtly political.”

Fate

A defining characteristic of Shakespearean tragedy is the tension between fate and human agency. Characters such as Macbeth, Hamlet, and Lear grapple with forces seemingly beyond their control, even as they make choices that seal their destinies. Dylan similarly crafts songs that explore fatalism, prophecy, and the inescapability of fate. All Along the Watchtower (1967) encapsulates this existential unease, with its apocalyptic imagery and cryptic dialogue between the joker and the thief:

"There must be some way out of here," said the joker to the thief,

"There's too much confusion, I can't get no relief."

This sense of entrapment and foreboding echoes Macbeth, where the titular character, after hearing the witches’ prophecies, feels powerless to resist his destiny, despite actively shaping it through his ambition. Much like Macbeth, the figures in All Along the Watchtower seem caught in a cycle they cannot break. As Ricks (2003) observes, Dylan’s fatalistic visions “share Shakespeare’s deep scepticism about human control over events.”

Love

Shakespeare’s plays frequently explore love’s illusions and the pain of betrayal, themes that Dylan also returns to in his songwriting. In Twelfth Night, love is deceptive and fluid, with mistaken identities and unfulfilled longing shaping the play’s comedic tension. Similarly, Othello portrays love as fragile and easily manipulated, leading to jealousy, doubt, and destruction. Dylan’s Visions of Johanna (1966) mirrors this Shakespearean preoccupation with the elusiveness of love. The song’s narrator is haunted by an absent figure, caught between memory and reality:

"Louise holds a handful of rain, tempting you to defy it."

Like Shakespeare’s protagonists, Dylan’s speaker is trapped in an emotional limbo, questioning whether love is real or merely an illusion. Barker (2018) notes that Dylan’s heartbreak ballads “share Shakespeare’s fascination with love as both a source of transcendence and a harbinger of despair.” This duality, where love is both intoxicating and destructive, aligns Dylan with Shakespeare’s complex portrayals of romantic relationships.

Power

Few writers have dissected the nature of political power as incisively as Shakespeare. His histories and tragedies, such as Julius Caesar and Richard III, examine the corrupting influence of ambition, the fragility of leadership, and the moral compromises made in the pursuit of power. Dylan’s Masters of War (1963) serves as a modern reflection of these concerns, offering a scathing critique of political and military leaders who exploit power for destruction:

"You that never done nothin’ but build to destroy,

You play with my world like it’s your little toy."

Like Richard III, which exposes the ruthless pragmatism of its protagonist’s rise to power, Dylan’s song denounces figures who wield authority without conscience. Shakespeare’s political tragedies often feature characters who manipulate public perception to justify their ambitions, mirrored in Dylan’s critique of leaders who justify war for personal or nationalistic gain. Thomas (2017) states that “Dylan, like Shakespeare, reveals the moral void at the heart of unchecked power, using poetry to expose deception and hypocrisy.”

Style and Language

Bob Dylan’s songwriting is not only thematically aligned with Shakespeare’s works but also demonstrates parallels with the Bard’s style. Dylan’s lyrics often incorporate: iambic rhythm, rhetorical devices, and monologue-like structures, all of which recall Shakespeare’s poetic and dramatic techniques. Additionally, his fondness for archaisms, intricate wordplay, and layered metaphors reflects a linguistic dexterity similar to Shakespeare’s. As Ricks (2003) argues, “Dylan’s command of language, like Shakespeare’s, lies in his ability to balance the formal and the vernacular, the grand and the intimate.”

Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets frequently employ iambic pentameter, a rhythm that closely resembles natural speech while lending a musical quality to his verse. Though Dylan does not adhere strictly to this metre, many of his lines exhibit a similar rhythmic quality. For example, in Like a Rolling Stone (1965), the refrain’s natural cadence resembles an iambic structure:

"How does it feel / to be on your own?"

This flowing, unstressed-stressed pattern enhances the song’s lyrical power and mirrors the way Shakespeare used rhythm to amplify meaning. Similarly, Dylan’s rhetorical flourishes such as anaphora (the repetition of phrases), antithesis (contrasting ideas), and rhetorical questioning, echo Shakespeare’s dramatic style. In A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall (1963), Dylan constructs a series of cascading questions, reminiscent of the Socratic and rhetorical questioning found in Shakespeare’s soliloquies:

"Oh, what did you see, my blue-eyed son?

Oh, what did you see, my darling young one?"

As Thomas (2017) notes, “Dylan’s lyricism, like Shakespeare’s poetry, relies on rhythmic intensity and rhetorical sophistication to heighten emotional and philosophical depth.”

Monologues

Many of Dylan’s songs unfold in a monologue-like fashion, resembling Shakespearean soliloquies in their introspective and often philosophical tone. Shakespeare’s soliloquies allow characters to reveal their innermost thoughts, exposing contradictions, regrets, or existential musings. Dylan employs a similar technique, particularly in songs where the narrator grapples with personal history and fate. Tangled Up in Blue (1975) depicts this storytelling approach, as the protagonist reflects on past relationships and shifting circumstances in a fragmented, nonlinear manner:

"We always did feel the same,

We just saw it from a different point of view."

This self-reflective mode aligns with the soliloquies of Hamlet or Macbeth, where the speaker’s mind is laid bare through a series of recollections and shifting emotions. As Barker (2018) suggests, “Dylan’s voice, like Shakespeare’s, operates within a dramatic framework where characters reveal themselves not through direct exposition, but through introspective confession.”

Wordplay

Shakespeare’s linguistic innovation is one of his defining features. His ability to coin new words, manipulate syntax, and layer meaning through metaphor and wordplay continues to shape English literature. Dylan, too, employs these techniques, infusing his lyrics with an old-world sensibility while simultaneously playing with language in fresh and unexpected ways. His use of archaisms: such as “thee,” “thy,” and biblical phraseology, recalls the formal register of Shakespearean English. In Farewell Angelina (1965), he crafts imagery that feels both timeless and literary:

"The sky is trembling, and I must leave."

Also, Dylan’s penchant for wordplay, puns, and layered metaphors aligns with Shakespeare’s use of language as a tool for multiple meanings. Desolation Row (1965), for instance, is filled with surreal, Shakespearean allusions and paradoxical imagery, blending historical and literary references into a single poetic vision. Ricks (2003) observes that “Dylan’s lyrics share Shakespeare’s delight in verbal ambiguity, where a phrase may conceal as much as it reveals.”

Their Shared Legacy

Bob Dylan and William Shakespeare occupy unique positions as literary figures who transcended their respective fields, reshaping language, culture, and storytelling traditions. While Shakespeare revolutionised drama and poetry in the early modern period, Dylan transformed songwriting into a form of high art, blurring the boundaries between music and literature. Both figures challenged conventions, leaving behind bodies of work that remain endlessly interpretable and influential. As Heylin (2021) argues, “Dylan, like Shakespeare, did not merely reflect his age, he redefined it, altering the very way in which narrative, language, and performance could be understood.”

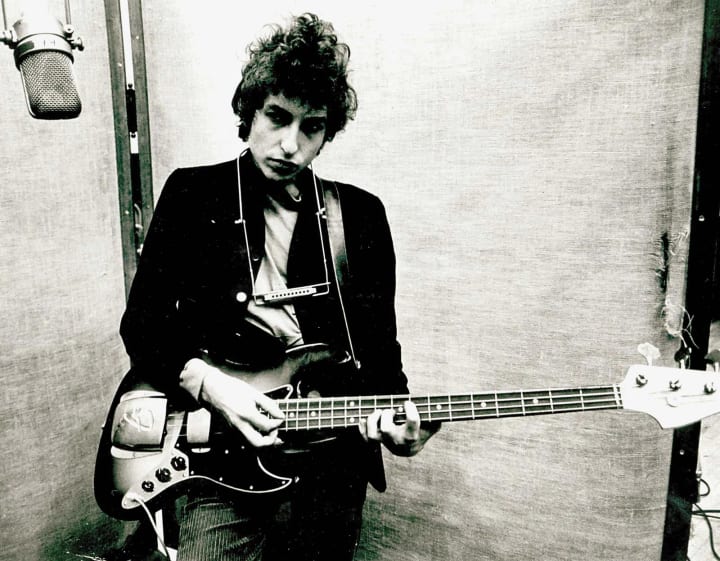

Shakespeare emerged at a time when English drama was evolving rapidly, and his ability to experiment with form, metre, and character psychology revolutionised the theatrical landscape (Wells, 2016). Similarly, Dylan rose to prominence during a period of social and musical upheaval in the 1960s, using folk and rock music as vehicles for complex poetic expression. His shift from traditional folk ballads to abstract, symbolic lyricism in Blonde on Blonde (1966) mirrors Shakespeare’s own evolution from conventional histories to the psychological depth of his later tragedies.

Both artists also resisted categorisation. Shakespeare moved seamlessly between genres: history, comedy, tragedy, often combining elements within a single play. Dylan, too, has reinvented himself across decades, shifting from folk to rock, gospel to blues, refusing to be confined to a single artistic identity. Marcus (2005) states, “Dylan and Shakespeare share a chameleon-like ability to change, ensuring their work remains fresh and vital, never settling into predictability.”

Few writers have had the same lasting impact on the English language as Shakespeare, whose phrases, idioms, and rhetorical structures have permeated everyday speech (Crystal, 2018). Dylan’s lyrics, too, have entered the cultural lexicon, influencing not only music but also literature and political discourse. His turns of phrase: such as “the times they are a-changin’”, carry an almost proverbial quality, much like Shakespearean expressions such as “to be or not to be.”

Also, both figures have influenced multiple art forms. Shakespeare’s plays have been adapted into countless films, operas, and novels, while Dylan’s music has inspired poets, novelists, and filmmakers alike. Todd Haynes’ I’m Not There (2007), a film exploring Dylan’s shifting identities, reflects the same fluidity of interpretation that characterises Shakespeare’s most enduring works. As Thomson (2013) observes, “Shakespeare and Dylan exist as cultural palimpsests, each new generation finds new meanings in their work, layering fresh interpretations over the old.”

The Nobel Prize Speech

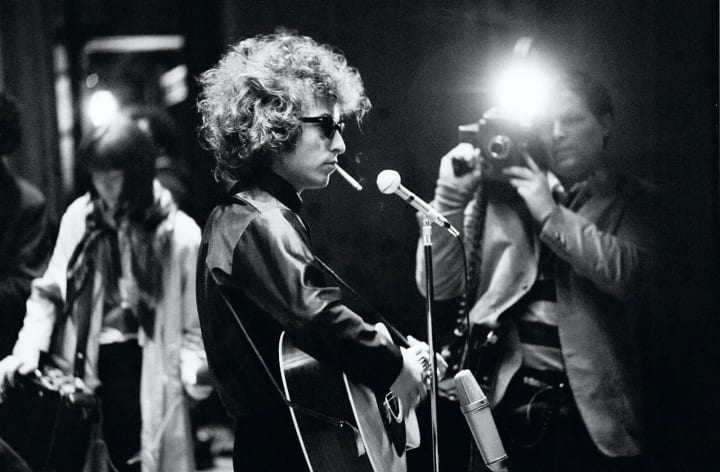

In 2016, Dylan became the first songwriter to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, a decision that sparked debate over the nature of literary merit. In his acceptance speech, Dylan reflected on the literary influences that shaped his work, naming Shakespeare among them. He drew a parallel between himself and the Bard, noting that while Shakespeare likely did not consider himself a “literary writer” in the conventional sense, his works carried profound artistic and philosophical weight (Dylan, 2017).

Dylan’s comparison is significant: Shakespeare’s plays were initially seen as entertainment rather than high literature, just as Dylan’s songwriting was often regarded as part of popular culture rather than serious art. However, both have come to be recognised as masters of language and storytelling, their works studied, analysed, and reinterpreted in literary contexts. As Weiss (2018) argues, “Dylan’s Nobel Prize speech reflects the same tension that surrounded Shakespeare’s legacy, the negotiation between performance and literary prestige, between popular appeal and intellectual depth.”

Conclusion

Bob Dylan’s connection to Shakespeare extends far beyond mere references or quotations. It is embedded in the very fabric of his storytelling, his use of character archetypes, and his exploration of universal themes. Like Shakespeare, Dylan creates dramatic, multi-layered narratives that transcend time and place, speaking to the fundamental aspects of human nature: love, betrayal, fate, and power. His songs, much like Shakespeare’s plays, resist a single interpretation, instead evolving with each listener’s perspective.

Both figures share an instinct for language’s musicality, crafting lines that feel at once natural and heightened. Shakespeare’s mastery of rhythm and wordplay finds an echo in Dylan’s lyrics, where he bends language to his own will, moving seamlessly between registers of speech. His ability to inhabit different voices: be it the wandering poet of Tangled Up in Blue or the cryptic figures of All Along the Watchtower, mirrors Shakespeare’s ability to bring a vast array of characters to life.

More than anything, Dylan and Shakespeare endure because they articulate the human experience with unparalleled poetic force. Their works speak across centuries, continually rediscovered and reinterpreted. Whether through a soliloquy or a ballad, both artists capture the complexities of existence in ways that feel at once deeply personal and profoundly universal. Dylan, like Shakespeare before him, understands that the power of words lies not just in what they say, but in how they resonate: shifting, refracting, and remaining eternally relevant.

Works Cited:

- Barker, H. (2018) Shakespeare and Popular Culture. London: Bloomsbury.

- Crystal, D. (2018) Shakespeare’s Words: A Glossary and Language Companion. London: Bloomsbury.

- Dylan, B. (2017) The Nobel Lecture in Literature 2016. London: Simon & Schuster.

- Heylin, C. (2021) The Double Life of Bob Dylan: Volume One, 1941–1966. London: Bodley Head.

- Marcus, G. (2005) Like a Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads. New York: PublicAffairs.

- Ricks, C. (2003) Dylan’s Visions of Sin. London: Penguin.

- Thomas, R. (2017) Why Dylan Matters. London: William Collins.

- Thomson, D. (2013) The Big Screen: The Story of the Movies. London: Penguin.

- Weiss, A. (2018) Dylan and the Nobel: The Troubadour in the Academy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wells, S. (2016) Shakespeare, Sex, and Love. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

About the Creator

Annie Kapur

I am:

🙋🏽♀️ Annie

📚 Avid Reader

📝 Reviewer and Commentator

🎓 Post-Grad Millennial (M.A)

***

I have:

📖 280K+ reads on Vocal

🫶🏼 Love for reading & research

🦋/X @AnnieWithBooks

***

🏡 UK

Comments (2)

Interesting breakdown of the Minnesota bard's work.

Very Informative.