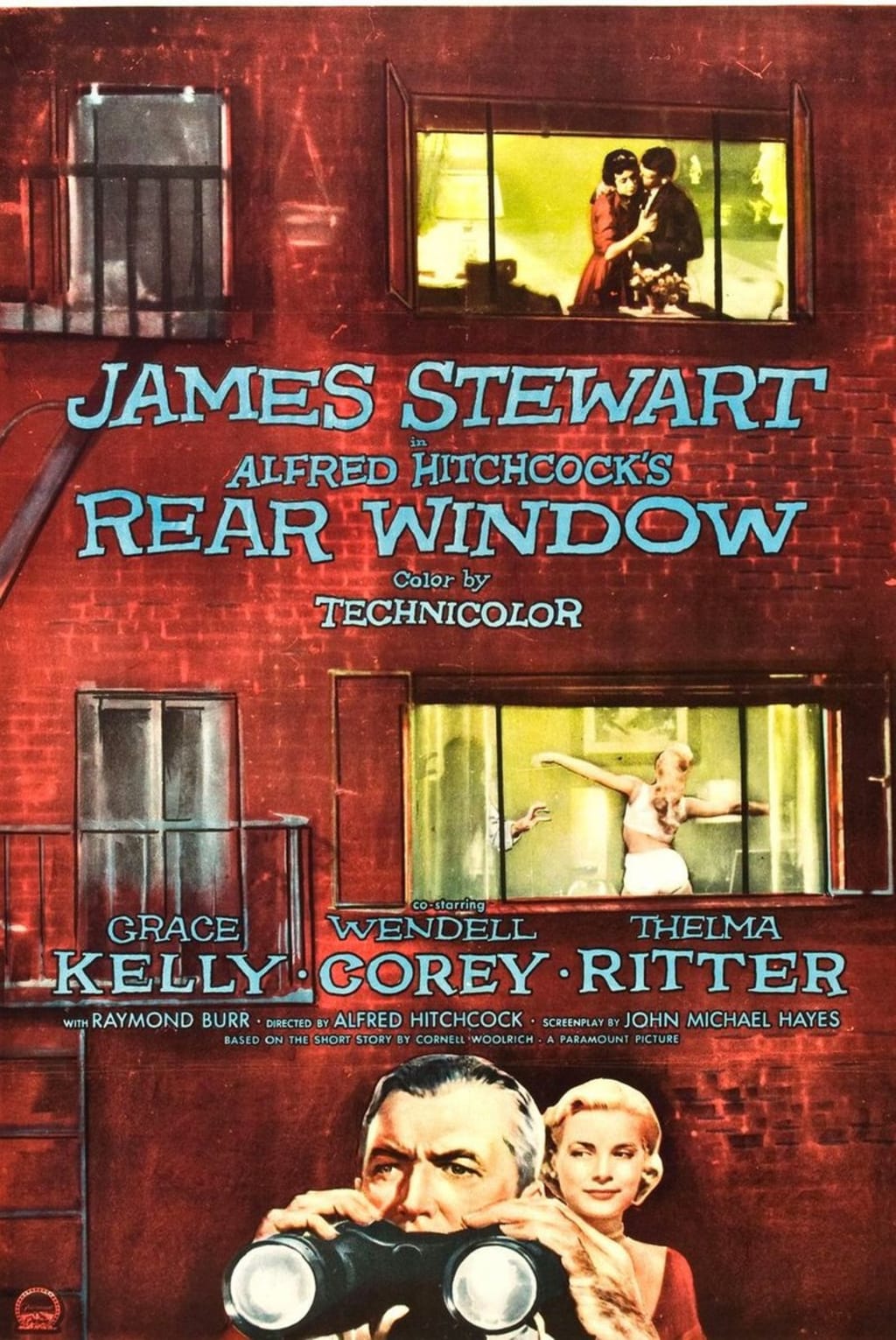

Perversion and Juxtaposition in Hitchcock's 'Rear Window'

Alfred Hitchcock corrupts our innocence via movie stars in Rear Window.

Rear Window

Directed by Alfred Hitchcock

Written by John Michael Hayes

Starring Jimmy Stewart, Grace Kelly, Raymond Burr

Released September 1st, 1954

Published March 12th, 2025

Alfred Hitchcock’s genius, for me, boils down to two elements: juxtaposition and perversion. Hitch takes a thing or a person associated with a specific characteristic and places that person or thing in a different context, one opposite to how we perceive it. The Birds (1963) is a great example. Before The Birds, no one associated birds with anything remotely dangerous. Hitchcock takes Birds and turns them into horror movie villains, convincing us through the use of storytelling and the tools of cinema that even the most innocuous animal can be used as a symbol of a battle between man and nature.

He enjoys this kind of juxtaposition in his actors as well. Take, for instance, Cary Grant in North by Northwest. Here, Hitchcock takes this bastion of handsomeness, charm, and good manners and repeatedly renders him helpless, hapless, and narrowly avoiding dangerous schemes not by his unending charm or good looks but by sheer chance and good luck. This flies in the face of our collective, cultural memory of Cary Grant as a debonair, accented charmer, a man constantly one step ahead of anyone he’s in a scene with. He is certainly the hero of North by Northwest but he does not drive the action, action happens to him. A leading man is supposed to be the catalyst of a story, Hitchcock takes the ultimate leading man of his time and robs him of his agency, forcing him to be subject to a plot rather than driving it. It's a juxtaposition of our expectations, of Grant's persona, and of the concept a leading man in a movie.

Rear Window also toys with our cultural perceptions of major movie stars. Jimmy Stewart is still regarded today as a bastion of mid-20th century virtue. Plain spoken, humble, and righteous, Stewart is the last man you’d cast as a pervert or as a man of anything less than impeccable virtue. This cultural perception is used against us in Rear Window as we meet Stewart as the character L.B ‘Jeff’ Jeffries. Jeff is confined to a wheelchair via a pretty nasty injury and spends his days staring out the window of his New York City apartment watching his neighbors as if they were channels on a wall of televisions. We see this as harmless simply because he’s Jimmy Stewart. Put a different actor in this position and it might be seen for what it is, creepy voyeurism. But it's different when Jimmy Stewart does it, right?

Grace Kelly plays Jeff’s love interest, Lisa Fremont, a successful model whom Jeff is trying desperately to break up with. In Jeff’s eyes, Lisa is too perfect. This plays directly into our cultural perception of the then future Princess Grace. Like Jeff, the public’s view of Grace Kelly was that of an impeccably virtuous symbol of feminine ideals. Immaculately put together, impossibly beautiful, Kelly is pure as driven snow in the minds of mid-20th century audiences. Even today, that perception of Kelly remains due to Kelly having ascended from Hollywood icon to actual royalty before dying tragically.

Via Kelly, we get to Hitchcock’s love of perversion. Perversion in this sense is not merely about objectification or sexuality, though those aspects are part of the overall package. No, in the case of Rear Window, the perversion comes in having Kelly lower herself to our level, taking the image of her perfection and perverting it, thus making her suitable for Jimmy Stewart’s perverted Jeff. The story hinges on Jeff’s voyeurism which leads him to believe that his neighbor, Thorwald (Raymond Burr), has murdered his nagging wife. At first, no one believes Jeff but Lisa quickly takes to the idea, seemingly as a way to finally reach the man who has so desperately tried to keep her at arms length, emotionally anyway.

Through their amateur detective game, Lisa goes from being the image of implacable perfection to literally getting arrested for burglary. The film establishes via a conversation between Jeff and his in-home caregiver, Stella (Thelma Ritter), that Lisa is too perfect and could never adapt to the life of an unglamorous, globetrotting photojournalist, living out of one suitcase, sleeping in cars and tents, and generally lacking the kind of Park Avenue style trappings where Lisa is assumed to be most at home. Thus, Lisa’s journey in Rear Window becomes showing that she can roll up her sleeves and get down in the muck.

She is essentially proving that she is capable of being a pervert, an equal voyeur to Jeff, one even more capable of getting her hands dirty. By investing herself in proving Thorwald killed his wife, Lisa allows her crafted perfection to slip away and reveal a humanity, curiosity, and moral flexibility that is entirely at odds with how we perceive both Lisa the character and Grace Kelly, the actress. It’s part of what makes her casting such a brilliant choice, we are thrilled on multiple levels, seeing her glamorous side via Edith Head’s glorious costuming and seeing her mask of perfection slip as she reveals the kind of sneakily perverse obsessions we all have deep down inside.

In the day and age of True Crime podcasts, this kind of perversion, this obsession with the macabre dark side of humanity, appears almost innocent. But in 1954, the sight of the pristine Grace Kelly becoming invested in a voyeuristic murder investigation was downright perverted. Hitchcock has taken our image of feminine perfection and perverted her, humanized her, and juxtaposed our perception versus the reality of the story he’s telling. It was thrilling and shocking for audiences in 1954 and the film is so enduring because it still feels thrilling today, even for those who are only discovering Kelly . The character of Lisa is a perfect extension of the Grace Kelly of 1950s myth until she starts getting into Jeff’s fantastical voyeuristic murder obsession and takes things further by going into the murderer’s apartment to search for evidence and gets caught and even taken away by the police.

How scandalous! I love it, pass the popcorn. Rear Window could likely succeed on the merits of being a well made thriller but in the hands of Hitchcock, the technical perfection is matched by his story sensibilities, his love of perverting innocence to reveal the flawed humanity at its core. Hitchcock’s masterful manipulation of our sympathies via his casting of Jimmy Stewart and Grace Kelly as obsessive voyeurs who happen to be on the side of good via catching a criminal far more insidious than a mere peeping tom, has secretly perverted us in the audience as well. We too are the voyeurs, complicit in Jeff and Lisa’s peeping tom voyeurism.

Hitchcock has perverted us in the audience, rendered us trusting peepers, eager to stare out that window to see what happens next, even as such a thing as peeping in your neighbors windows, regardless of what they are doing, is, if not criminal, per se, it is creepy and transgressive. Generally speaking, you should not be looking through your neighbors windows, regardless of your proximity to said neighbors and their willingness to leave the curtains open. If you were to be peeping through the windows of your neighbors today, you’d likely get a visit from the police or, at the very least, a punch in the face from a violated neighbor.

But, place that voyeurism in the hands of Jimmy Stewart and Grace Kelly, via the safe distance of a movie screen, and the juxtaposition of the crime of peeping in windows enters a realm of moral flexibility. If Jimmy and Grace, paragons of all American virtue can peep in windows, certainly it’s okay for us to join them, right? Plus, they have the virtuous cause of solving a murder. Nevermind the time spent objectifying Miss Torso (Georgine Darcy) or casting judgments upon Miss Lonelyhearts (Judith Evelyn) or ‘The Songwriter’ (Ross Bagdasarian), whom we also frequently peep on, it’s about catching a murderer you guys. This is voyeurism with a just cause.

Alfred Hitchcock makes conspiring with Jimmy Stewart and Grace Kelly, into an example of just how morally flexible we all can be. We trust these people, we view them as morally unimpeachable, they get us to let our guards down and suddenly we’re peeping in windows and passing it off as good fun even before it takes on a righteous cause, catching a killer. By comparison, we’re doing the right and just thing, but we’ve already compromised ourselves simply by allowing ourselves to identify with and excuse Jimmy Stewart his perverse fascination with looking in his neighbor’s windows and cheering on Grace Kelly as she commits a legit burglary, because the comparative crime she’s fighting is worse. It’s a masterful trick, one that perfectly embodies Hitchcock’s most unique qualities, perversion and juxtaposition.

Find my archive of more than 24 years and more than 2000 movie reviews at SeanattheMovies.blogspot.com. Find my modern review archive on my Vocal Profile, linked here. Follow me on Twitter at PodcastSean. Follow the archive blog on Twitter at SeanattheMovies. Also join me on BlueSky, linked here. Listen to me talk about movies on the I Hate Critics Movie Review Podcast. If you have enjoyed what you have read, consider subscribing to my writing on Vocal. If you’d like to support my writing, you can do so by making a monthly pledge or by leaving a one time tip. Thanks!

About the Creator

Sean Patrick

Hello, my name is Sean Patrick He/Him, and I am a film critic and podcast host for the I Hate Critics Movie Review Podcast I am a voting member of the Critics Choice Association, the group behind the annual Critics Choice Awards.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.