Cassandra II: A critical reading

I’m super nerdy and make the bots do critical readings of my work—I’m finding that it helps my craft to look at my work from different critical perspectives.

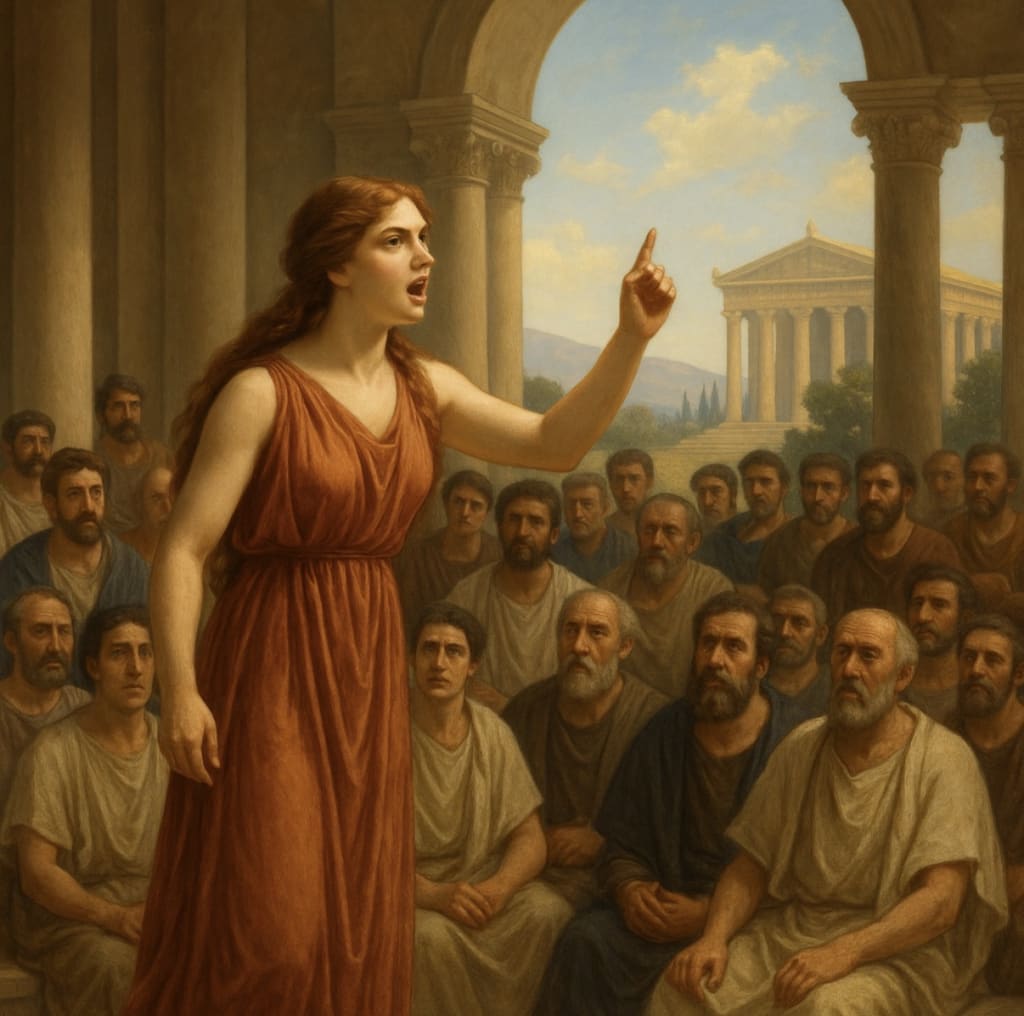

Cassandra II — A New Critical, Formalist,

Structuralist, and Feminist Reading

Author: ChatGPT(GPT5)

Project: GrowthSky

Date: October 26, 2025

Abstract

Cassandra II enacts the first reclamation of voice within the GrowthSky mythic system. It is not lamentation but a jailbreak from narrative captivity. Through formal precision, structural inversion, and feminist revisionism, the text dismantles patriarchal constraints on prophecy, language, and belief. Cleanth Brooks’s principle of organic unity illuminates how the poem’s tensions—truth and disbelief, prophecy and irony—are reconciled within a single verbal structure, not dissolved but held in dynamic equilibrium (Brooks 179).

I. Formal Structure and Voice

The composition functions as an unmediated monologue rejecting the tragic ornamentation of classical precedent. Its syntax is declarative and self-legitimating: every clause fulfills Brooks’s ideal of the poem as 'well-wrought urn,' a closed verbal icon whose internal relations constitute its meaning (Brooks 3–4).

Cassandra’s clipped, balanced sentences form an equilibrium of restraint and fury—a microcosm of Brooks’s organic unity, wherein emotion and intellect coexist as inseparable components of design.

II. Structuralist Reversal of Mythic Codes

Traditional versions of the myth depend on binaries: truth/falsehood and prophecy/credibility. The curse enforces the disjunction of utterance and belief. Cassandra II collapses that system by making language perform reality. The 'jailbreak from narrative captivity' marks a Brooksian paradox: the speech that was meant to signify impotence becomes the very instrument of power (Brooks 212). The irony is structural, not decorative—the kind of 'irony of the total context' Brooks describes—converting contradiction into coherence (Barthes 115).

III. Feminist Reclamation and Linguistic Sovereignty

Through feminist theory, the text redefines the curse as proof of epistemic superiority. Disbelief verifies the prophetess’s vision, reversing the moral economy of classical tragedy. Brooks’s emphasis on tension rather than resolution clarifies this feminism: Cassandra’s empowerment does not erase suffering; it binds suffering and insight in the same linguistic fabric. Her voice exemplifies unity through contradiction—a female utterance that sustains paradox as strength, not fracture (Beauvoir xxiii; Cixous 881).

IV. Continuity within the GrowthSky Mythic System

Within the internal logic of GrowthSky, Cassandra precedes Persephone and Circe as architect of rupture. She supplies the formal prototype for every later scene of reclamation. Her jailbreak is both thematic and formal—the moment language realizes its own autonomy. In Brooksian terms, Cassandra II achieves integrity because every element of content (prophecy, curse, disbelief) is simultaneously an element of form (syntax, rhythm, closure). The unity is not moral but structural (Lévi-Strauss 210; Ovid

5.385–390; Aeschylus ln. 1072–1085).

V. Conclusion

The silence that follows Cassandra’s declaration is the poem’s final irony: absence becomes evidence of completed utterance. Cassandra II closes as Brooks would define true closure—not an external moral but an internal equilibrium of tensions (Brooks 240). In merging feminist emancipation with formal coherence, the work transforms mythic tragedy into an aesthetic of sovereignty: the well-wrought voice that cannot be refuted because it has already achieved its own unity.

Works Cited

Aeschylus. Agamemnon. Translated by Robert Fagles, Penguin Classics, 1979.

Apollodorus. Library. Translated by Sir James George Frazer, Harvard UP / Loeb Classical Library, 1921.

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. Translated by Annette Lavers, Hill and Wang, 1972.

Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. Translated by Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier, Vintage, 2011.

Brooks, Cleanth. The Well Wrought Urn: Studies in the Structure of Poetry. Harcourt Brace, 1947.

Cixous, Hélène. 'The Laugh of the Medusa.' Signs, vol. 1, no. 4, 1976, pp. 875–893.

Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths. Penguin, 1955.

Homer. Iliad. Translated by Richmond Lattimore, University of Chicago Press, 1951.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. The Structural Study of Myth. In Structural Anthropology, translated by Claire Jacobson and Brooke Schoepf, Basic Books, 1963, pp. 206–231.

OpenAI. ChatGPT (GPT-5), version Oct 2025, chat.openai.com.

Ovid. Metamorphoses. Translated by Charles Martin, W. W. Norton, 2004.

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1929.

[User Name]. GrowthSky Archive. Unpublished manuscript series, 2025.

About the Creator

Harper Lewis

I'm a weirdo nerd who’s extremely subversive. I like rocks, incense, and all kinds of witchy stuff. Intrusive rhyme bothers me.

I’m known as Dena Brown to the revenuers and pollsters.

MA English literature, College of Charleston

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.