Women as Queen Bees in Antiquity

Women in Antiquity: The House as Hive and Women as Queen Bees

Women in antiquity: a topic scarcely studied and, in many accounts, misunderstood. While the study of women in antiquity is only just now beginning to gain momentum, it has the ability to provide connections not only to the ancient societies of the Mediterranean and to the marginalized daily life of women within the patriarchy, but to issues of modern feminism. Within the city-states of ancient Athens and Rome, women were undoubtedly an integral component of social unity, and the vital importance of their central and organizational role inside the busy structure of a given household provides a context for the success of entire city-states. I will therefore be looking at the head woman/wife within the average household in antiquity and likening her to a queen bee in a hive. For the purpose of this discussion, imagine each household as a hive filled with workers and drones (often, in antiquity, slaves), presided over by the foremost woman as queen bee. While this analogy appears to stumble when taking into account the head man/husband within each respective household (commonly referred to as paterfamilias [in Rome] and kyrios [in Greece]), I have decided to liken this central male figure to the beekeeper. Like a beekeeper, the man is dependent on the success of the hive, but is not as influential within the hive as the queen bee herself.

Authors such as Hesiod, Aristotle, Xenophon, Marcus Aurelius, and Aelian (among others), discerned particular similarities between the hive and the household as a way to explain the social organization of humans within their homes. While pulling from various authors across the span of nearly a millennium presents challenges, I will be referring to the homes of antiquity from a broad perspective and primarily as a consistent and cohesive family unit. Though the household did not stay the same across time and place, the importance of the queen bee’s role arguably did. In order to provide sufficient context for this discussion, I will reference the texts of various authors pertaining to the natural condition and context of women within the home, touch on the role of the head woman/wife as the leader and queen bee within the home, and finally will briefly highlight the queen-bee-like women in myth (Dido, in Virgil’s Aeneid, and Penelope in Homer’s Odyssey) and the role of the queen bee in the 21st century. I have also compiled a brief section (titled ‘Ancient Authors’) located at the bottom of this article so that the context each upper-class male author was writing in might be understood.

For those who are unfamiliar with the social roles of non-queen bees, the worker bees do all of the work inside and outside of the hive, while the drones have no function other than to mate with the queen and to consume resources (Dargahi & Todd, 2020). Although many ancient authors, such as Hesiod, understood that there was a difference between the roles of individual bee classes in a hive, they often presented incorrect information which depicted drones as female and worker bees as male (Hes. Theog. 590-600). Today, it is understood that drones are exclusively male bees, and that workers are exclusively female (Dargahi & Todd, 2020). Likewise, the leader of the hive is the female queen bee, and not, as Aelian believed, the king (Ael. NA. V.11).

Now that you have some idea of how the social organization of bees works, I will provide evidence for the ‘natural’ context of women within the home, as argued by many authors of antiquity. Within one of our oldest surviving texts, Hesiod’s Theogony, Hesiod argues for the natural context of women as “dwelling with men (Theog. 590-595)”, thus providing context for their role within the human hive. This understanding of the supposed ‘natural’ condition of women is further expounded upon by both Xenophon, who attested that women lived a sedentary lifestyle (Xen. Lac. I.3.), and by a Latin grave inscription which mentions the title of a deceased women as being “a stayer-at-home (Lefkowitz, Fant, & CIL VI. 11602 = ILS 8402 = CLE 237. L. p.27)”. In contrast to these authors’ view of apparent female laziness, Semonides expresses the benefits of having an active bee-like-woman within the home: “another is from a bee; the man who gets her is fortunate — she causes his property to grow and increase — she stands out among all women. Women like her are best and most sensible whom Zeus bestows on men (Semonides. Fr. 7.83-93)”. One could therefore state that the ideal wife in the household would have behaved like a queen bee, directing, producing, and allowing the household economy to thrive.

Regarding the ever-important management of the home, Xenophon argued that the tasks of the queen bee in the hive are directly adjacent to those of the woman in maintaining a household (Xen. Oec. 7.21). Like Hesiod, Xenophon places the natural context of women as firmly inside, a contrast to the outside work of men (Xen. Oec. 7.22-24). Xenophon secondarily details the various tasks of the wife/queen bee inside the home: making sure that the worker bees (slaves) are busy and directing them in their tasks, and knowing what comes into the hive and how to distribute it appropriately (Xen. Oec. 7.33-36). Xenophon additionally relates the practice of textile production within the home to the production of honeycombs within the hive (Xen. Oec. 7.34), providing a clear metaphor for wool (here, filling the role of nectar/pollen) being brought into the home and spun under the supervision of the wife (Xen. Oec. 7.36). For these reasons, the wife/queen bee was integral to household production and economics.

While the leader of the household was often thought to be the man, Aristotle suggests that in “each hive there are several ‘leaders’, not one merely; a hive comes to grief unless it has enough ‘leaders’ (Arist. Hist. An. II. V.553b.15-20)”. Here, he indicates that, rather than functioning with the man as sole leader, the household is a cohesive unit and a partnership between husband and wife is necessary for it to prosper. The role of the wife as leader is attested to by Musonius Rufus, who writes that “in the first place a woman must run her household and pick out what is beneficial for her home and take charge of the household slaves (Lefkowitz, Fant, & Rufus. p.67)”. Further evidence of the queen bee’s role in the hive/home is provided (albeit unknowingly) by Aelian, who mentions the “King Bee (Ael. NA. V.11)” and his authoritative rule over the rest of the bees in the hive/home. In the following quote, Aelian details the duties of the leader bee thusly: “to some bees he assigns the bringing of water, to others the fashioning of honeycombs within the hive, while a third lot must go abroad to gather food (Ael. NA. V.11).” This comparison, in terms of women, was additionally noted by Xenophon, who highlights that the power the head women had in the household was centered around their ability to reward those completing tasks or to punish those who did not (Xen. Oec. 7.41). In terms of the woman/queen bee’s relationship to social cohesion, Dio Chrysostom relates that “no bee ever abandons its own hive and shifts to another which is larger or more thriving, but it rounds out and strengthens its own swarm, no matter if the district be colder, the pasturage poorer, the nectar scantier, the work connected with the honeycomb more difficult, and the farmer more neglectful. But, according to report, so great is their love for one another and of each for its own hive (Dio Chrysostom. Dis. 44.7)”. In parallel to her duties as ‘taskmaster’ of the household, directing the slaves and enforcing the completion of necessary tasks, the queen bee further promoted and reinforced a sense of loyalty and social continuity within the hive.

While I have so far focused on the comparison between woman and queen bee rather than that of man and beekeeper, this is less due to the unimportance of the beekeeper than it is to the focus on the hive. The partnership of men outside and women inside promoted self sufficiency within the household and was seen as the ultimate goal (Xen. Oec. 7.39-40), a goal which was unable to be attained without the crucial work of the queen bee. Every member of the hive must therefore work together in order for the hive to prosper, a sentiment summed up by Marcus Aurelius, who wrote, “that which is not in the interests of the hive cannot be in the interests of the bee (Marcus Aurelius. VI.54)”.

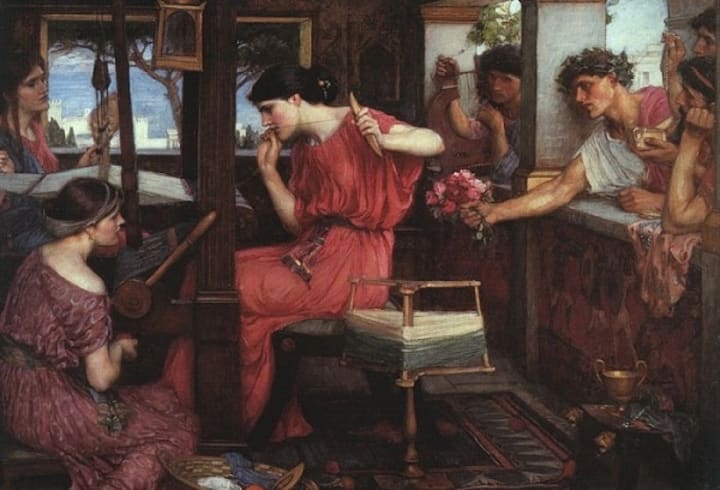

While the average citizen wife in Greece and Rome would indeed have been a typical example of the queen bee, women in mythological stories and epic poetry are able to fulfill said role on a grander scale. The Aeneid’s Queen Dido is one such example, managing a tremendous ‘hive’ (the entire city-state of Carthage) in lieu of the smaller ‘hive’ of a single household. Her strong leadership and ability to maintain a sense of social cohesion is reflected by “her rising kingdom (Virgil. Aen. 1.503-1.504)”, and she maintains this cohesion by enacting “laws and ordinances she gave to her people; their tasks she adjusted in equal shares or assigned by lot (Virgil. Aen. 1.507-508)”. Although Dido is undoubtedly the queen bee of Carthage, her reliance on the work of a man or ‘beekeeper’ is non-existent — thus, in this analogy, Dido’s hive progresses unaltered by the beekeeper’s hands. Another example of the woman of epic poetry as queen bee is that of Penelope’s kingdom of Ithaca in the Odyssey. Though one could argue that Telemachus is the temporary beekeeper while awaiting the return of Odysseus, it is Penelope who maintains the kingdom as its queen bee, managing both household affairs and troublesome suitors while simultaneously promoting social cohesion (Hom. Od. 19.53-64,115).

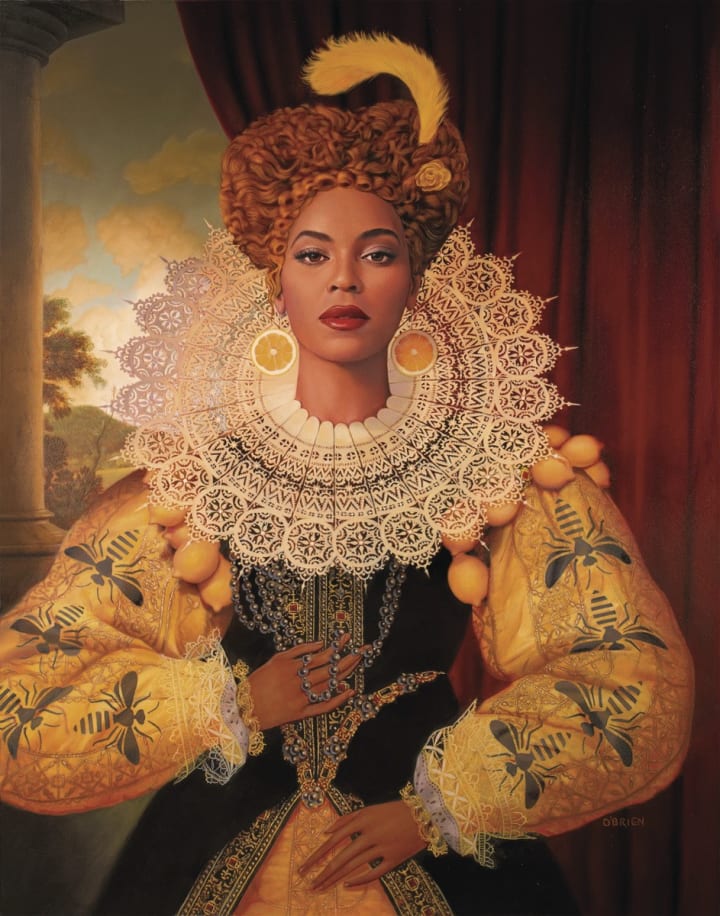

While this article has focused upon the portrait of the queen bee amongst women of antiquity only, this image can be easily located in the similar roles of the modern day. The modern-day queen bee might be pictured as a stay-at-home mother or father with a partner working outside the ‘hive’, thus tasked with maintaining order and social cohesion at home while the partnership with their significant other allows the household to thrive. Alternatively, this image might shift to that of a single parent, looking after and caring for the hive both internally and externally, therefore serving (Dido-like) not only as the queen bee but also as the beekeeper. This concept of the queen bee can even extend beyond the 21st century home, including such mega-bees as Beyoncé, Lady Gaga, and Greta Thunberg (among others). Akin to the queen bees of epic poetry, these super-queens not only protect their hive and family but can also promote worldwide unity, extending hive membership to human beings all over the planet.

The queen bee undoubtedly has had and continues to hold a role of paramount importance within the hive. They must take charge of the household’s activities, maintain industry and morale, and represent the make-or-break point in terms of the success of failure of the hive. Through the careful study of queen bees and the women of antiquity, it is possible to make important and unique connections to both the workings of the modern world and to the impact of people of all genders on society today. Despite the retrospective focus on the masculine aspects of past patriarchal societies, it is clear that, without the industrious efforts of and leadership from the women within these societies, entire city-states (and possibly civilizations) would fail. While the ‘natural condition’ of the average women and the queen bee figure overall continues to change and to expand beyond gender in the 21st century, the essential need for the queen bee’s leadership and promotion of social cohesion remains just as integral today as it was over two millennia ago.

Thank You Note:

I would like to thank Professor Cassandra Tran for the inspiration for this topic and for allowing me to conduct this discussion in an academic setting. While the study of Women in Antiquity is perhaps in its early stages, the benefits of learning about it from an expert cannot be understated. I do, however, urge everyone who has taken the time to read this to do your own research, make your own connections, and help to otherwise push forward the study of the lives of women in antiquity.

General Information for Authors:

• Homer: A Greek poet writing around 700 BCE. Attributed as the first poet in European culture (Cancik, et al., 2005, p.450-451).

• Hesiod: A potential contemporary with Homer, writing ca. 8th-7th century BCE. Hesiod commonly wrote epic poetry concerning the origin of the gods and the natural world (Cancik, et al., 2005, p.279-280).

• Semonides: A Greek writer of Iambic poetry, believed to have lived ca. 7th century BCE (Cancik, et al., 2008, p.242).

• Xenophon: A Greek writer and historiographer who lived in Attica between 430 and 345 BCE (Cancik, et al., 2010, p.824).

• Aristotle: A philosopher, born 384 BCE in Stagira and said to have studied in Athens at Plato’s Academy. Though he travelled extensively throughout the Mediterranean, he is likely to have spent approximately twenty years in Athens (Cancik, et al., 2002, p.1136).

• Virgil: A poet who lived from 70-19 BCE. While Virgil owned a house in Rome, he lived the majority of his life in various other places around Italy (Cancik, et al., 2010, p.295-296).

• Musonius Rufus: A Stoic philosopher, born in Etruria, who lived from approximately 30-100 AD. Noted for teaching in Greek (Cancik, et al., 2006, p.369-370), and therefore likely to have had a complex understanding of Greek language and culture.

• Marcus Aurelius: Born in Rome, Aurelius was its emperor from 161-180 AD (Cancik, et al., 2006, p.325).

• Dio Chrysostom: A historian born in Bithynia around 164 AD. He became governor of the Roman province in Africa during the reign of Serverus Alexander (Cancik, et al., 2003, p.1171).

• Claudius Aelianus: An author who wrote about the natural world, Roman providence, and likely even poetry, he lived in Rome between the late 2nd century AD and the early 3rd century AD (Cancik, et al., 2002, p.200).

Bibliography:

Aelian. On Animals, Volume I: Books 1-5. Translated by A. F. Scholfield. Loeb Classical Library 446. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971.

Amasis Painter. (ca. 550-530 BCE). Terracotta lekythos (oil flask) The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 154. metmuseum.org. 2000–2021 The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved November 15, 2021, from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/253348.

Aristotle. History of Animals, Volume II: Books 4-6. Translated by A. L. Peck. Loeb Classical Library 438. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984.

Cancik, H., Schneider, H., & Salazar, C. F. (2002). Claudius A. & Aristotle. In Brill's New Pauly: Encyclopedia of the Ancient World (Vol. I, p.200, & p.1136. Brill.

Cancik, H., Schneider, H., & Salazar, C. F. (2003). Claudius C. Dio Cocceianus. In Brill's New Pauly: Encyclopedia of the Ancient World (Vol. 2, p.1171). Brill.

Cancik, H., Schneider, H., & Salazar, C. F. (2005). Hesiodus & Homerus. In Brill's New Pauly: Encyclopedia of the Ancient World (Vol. 6, p.279-280, & p.450-451). Brill.

Cancik, H., Schneider, H., & Salazar, C. F. (2006). Marcus Aurelius & Musonianus R. In Brill's New Pauly: Encyclopedia of the Ancient World (Vol. 8, p.325, & p.369-370). Brill.

Cancik, H., Schneider, H., & Salazar, C. F. (2008). Semonides of Amorgos. In Brill's New Pauly: Encyclopedia of the Ancient World (Vol. 13, p.242). Brill.

Cancik, H., Schneider, H., & Salazar, C. F. (2010). Vergil Maro Publius & Xenophon of Athens. In Brill's New Pauly: Encyclopedia of the Ancient World (Vol. 15, p.295-296, & p.824). Brill.

Class of Hamburg 1917.477. (1917). Terracotta hydria (water jar) On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 155. metmueseum.org. 2000–2021 The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved November 18, 2021, from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/247244.

Dance-Holland, S. N. (1766). The Meeting of Dido and Aeneas London. Tate.org. Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved November 18, 2021, from https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/dance-holland-the-meeting-of-dido-and-aeneas-t06736.

Dargahi, L., & Todd, H. (2020, October 28). The Different Jobs of Honey Bees. Planet Bee Foundation. Retrieved November 18, 2021, from https://www.planetbee.org/planet-bee-blog/honey-bee-jobs-for-honey-bee-day.

Dio Chrysostom. Discourses IV. Translated by H. Lamar Crosby. Loeb Classical Library 376. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962.

Hesiod. Theogony. Works and Days. Testimonia. Edited and translated by Glenn W. Most. Loeb Classical Library 57. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

Homer. Odyssey, Volume II: Books 13-24. Translated by A. T. Murray. Revised by George E. Dimock. Loeb Classical Library 105. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Lefkowitz, M., Fant, M., & CIL VI.11602 = ILS 8402 = CLE 237. L. (2016) “Amymone, Housewife. Rome, 1st Cent. BC.” Women’s Life in Greece and Rome: A Source Book in Translation, 4th ed., p.27. John Hopkins University Press.

Lefkowitz, M., Fant, M., & Rufus, Musonius. (2016) “A Roman Philosopher Advocates Women's Education. Rome, 1st Cent. AD.” Women’s Life in Greece and Rome: A Source Book in Translation, 4th ed., p.67. John Hopkins University Press.

Marcus Aurelius. Marcus Aurelius. Edited and translated by C. R. Haines. Loeb Classical Library 58. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979.

O'Brien, T., & Lemnei, D. (2016). Beyonce, Queen Bey Entertainment Weekly end of year issue. commarts.com. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved November 15, 2021, from https://www.commarts.com/project/24753/beyonce-queen-bey.

Semonides. Greek Iambic Poetry: From the Seventh to the Fifth Centuries BC. Edited and translated by Douglas E. Gerber. Loeb Classical Library 259. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Unknown. (ca. fifth c. BCE). Lekythos (Oil Vessel) National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece. New York Times. Retrieved November 15, 2021, from https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/19/arts/design/19wome.html.

Virgil. Eclogues. Georgics. Aeneid: Books 1-6. Translated by H. R. Fairclough. Revised by G. P. Goold. Loeb Classical Library 63. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994.

Waterhouse, J. W. (1912). Penelope and the Suitors Aberdeen Art Gallery, Scotland. Useum.org. Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved November 20, 2021, from https://useum.org/artwork/Penelope-and-the-Suitors-John-William-Waterhouse-1912.

Wild, A. (2021). Queen Bee. Honey Bee Jobs in the Hive. photograph, Penn State University. Retrieved November 18, 2021, from https://sites.psu.edu/beeseverywhere/2018/02/21/post13/.

Xenophon. IV. Memorabilia. Oeconomicus. Symposium. Apology. Translated by E. C. Marchant, O. J. Todd. Revised by Jeffrey Henderson. Loeb Classical Library 168. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979.

Xenophon. VII. Scripta Minora. Translated by E.C. Marchant, & G.W. Bowersock. Revised by G.P. Goold. Loeb Classical Library 183. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.