Titanic's Sister: A Dark Secret? PART ONE

Did the Titanic Truly Sink?

Prologue

The sinking of the passenger ship Titanic is one of the most tragic and famous stories of all time. Her story is known all over the world, thanks to how well documented it is. From books, film, websites, social media, video games and music. But with any disaster, as long as there are unanswered questions, research will continue. While research continues, newer evidence will always be uncovered, and sometimes evidence that may pull us away from the accepted story as we have been told. Newer evidence has been uncovered regarding the Titanic, that may point us towards a horrifying new reality. A reality in which the ship that fell two and a half miles to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean, was NOT the Titanic, but her sister ship Olympic, and that the disaster was not a pure, simple accident, but something very sinister. With evidence on both sides, we are left with a chilling question, which of the two ships rests on the ocean floor today?

The White Star Line

The Olympic and the Titanic were built for the British shipping company White Star Line, as a response to competition imposed by the venerable fellow British shipping company, Cunard. The two sisters were built at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast, Northern Ireland, which was an exclusive agreement between the two firms. The company itself was founded in 1845 by John Pilkington and Henry Wilson, where it chartered ships from other lines to get on its feet. To begin with, it focussed on the Australian routes. In 1854, however they suffered a loss that haunted them for years, the RMS Tayleur an advanced iron-hulled ship built by a charter contact, sank off the coats of Ireland. Of the passengers and crew onboard, 327 of them were lost. In 1863, the company chartered its first steam-powered vessel, the Royal Standard. Later, it began participating in the North Atlantic Passenger Market. The passenger market was already an extremely competitive venture, and investment in new ships kept growing thanks to borrowing from the Royal Bank of Liverpool. The Royal Bank of Liverpool failed in 1867 and the company was left with £527,000 of debt. In 1868, the company was bought by Thomas Ismay for £1,000, where he commissioned the Oceanic and it sisters, the Atlantic, the Baltic and the Republic. The White Star Line prospered thanks to Ismay, not just in the operation of fast, safe and luxurious ships, but also thanks to an exclusive agreement in which Gustav Schwabe and Gustav Wolff would provide finance for the company providing it had its ships built by Harland and Wolff. In the 1870s, the Republic and the Baltic captured the Blue Riband for White Star Line. White Star Line were not an independent company at the time, in 1902 the company was sold by its chairman, Joseph Bruce Ismay to the International Mercantile Marine, a trust chaired by John Pierpont Morgan whose ambition was to monopolise the North Atlantic passenger market, which was very lucrative and very competitive. Apart from Cunard, every single passenger shipping company operating in the North Atlantic passenger market was owned by Morgan. Lord William James Pirrie, the chairman of Harland and Wolff had the role of bringing together Britain's excellence in engineering and Morgan's money.

Insurance Fraud vs. Minuscule Profits?

Ever since the 1860s, immigration had become an immense business venture for shipping companies and by that point were well aware that carrying large quantities of penniless immigrants from Europe to the United States was as profitable as carrying small numbers of rich and overly privileged passengers. Thanks to how many people wished to enter the United States or other countries on that side of the Atlantic, the passenger market became more and more competitive and companies fought for a share of this ever expanding and lucrative market. This was achieved by building bigger, faster and more luxurious liners, which were always prone to being overloaded and over insured: a perfect leeway for fraud. In the early 1870s, Samuel Plimsoll published a statement in Our Seamen that ships could only reach destinations in good weather and that companies preferred to have their ships sink and claim the insurance for the damned vessels. This, Plimsoll stated, was more financially beneficial than having ships run on a regular basis and bring in supposedly minuscule profits.

White Star Line were no strangers to disaster at the time of the sinking of the Titanic, 39 years previously they suffered their first ever loss at sea since they were saved from liquidation by Thomas Ismay, Bruce Ismay's father. The second ever ship of their commissioning, the Steamship Atlantic foundered off the coast of Nova Scotia. Atlantic became the deadliest single shipwreck ever recorded at the time, as well as seeing only one child and not a single woman survive. In the aftermath, despite their very existence being threatened by the loss of the SS Atlantic, White Star Line were paid £150,000 in insurance when the ship only cost £125,000 to commission. Though Atlantic has never been proven to be an insurance scam, this does show the leeway to fraud.

The Hawke Collision

On June 14th, 1911, Olympic departed from Southampton on her maiden voyage, commanded by Edward John Smith. Smith was the White Star Line's commodore and holder of the nickname "millionaire's captain" thanks to how many rich and powerful men would change their travel arrangements so that they could travel on a ship commanded by Smith. June 21st, a week later, Olympic arrived in New York but upon arrival a tugboat by the name of O.L. Hallenbeck was sucked under her stern and was so badly damaged she nearly sank. Olympic only suffered some paint scratches, but this was however a dark foreshadowing.

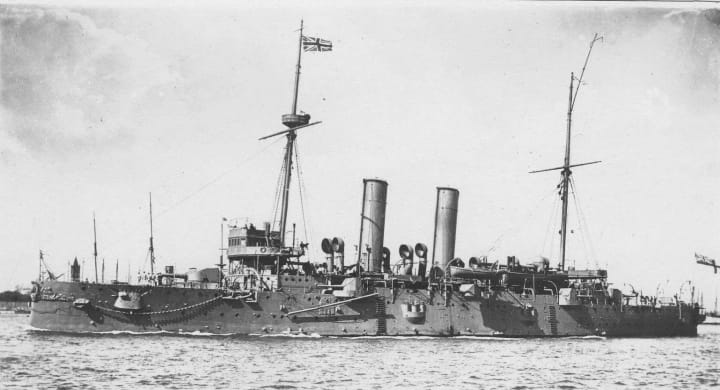

On September 20th, 1911, Olympic commenced her fifth voyage from Southampton to New York. In the Solent, she came into contact with the Royal Navy ship HMS Hawke, an Edgar-class protected cruiser. Hawke was fitted with an underwater ram, which was originally designed to sink an enemy ship by ramming into them and inflicting as much damage as possible. The two ships began to sail parallel to one another, at a very acute angle. Hawke gained right of way, but Olympic increased her speed and overtook Hawke. At that moment, Hawke was caught in the suction from Olympic's propellers, and she veered out of control and smashed into the side of the mighty liner. Her underwater ram, penetrated the starboard side of Olympic, creating two large holes in her side (one below the waterline and a bigger one above), indenting/tearing the propeller shaft bossing, badly bending the propeller shaft out of shape, straining the low pressure crankshaft, and chipping the blades on the starboard propeller.

If that was bad enough, Hawke twisted towards the aft end of Olympic, then spun away like a top, nearly capsizing. Her bow was badly crushed, her ram was torn off, and her seams were badly ruptured with popped rivets. If it were not for hastily rigged collision matts, Hawke would have sunk.

The collision between Olympic and Hawke was investigated by the British Admiralty, who upon finding out that Olympic overtook Hawke when the latter had right of way, found the former to be at fault. As a consequence of this, Lloyd's of London, the White Star Line's insurers would not cover the cost of repairs to Olympic.

A Dark Secret?

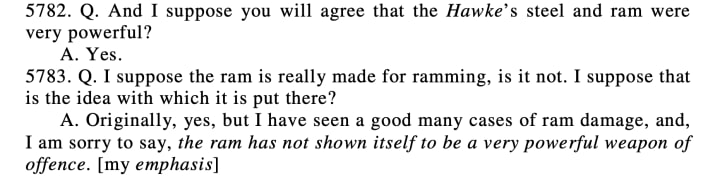

After the collision, Olympic limped back to Southampton where her passengers were disembarked and directed to find alternative travel arrangements. After the damage was inspected, she was then patched up using steel plates below the waterline and wooden coverings above. The patching up took two weeks to complete, and when it was, Olympic limped back to Harland and Wolff for further repairs. During the voyage, not only did the temporary patch up begin to fail, only one engine was running, the ship seemed to be vibrating uncontrollably and listing to port. In 1997, a diagram of the starboard profile of Olympic was released by Harland and Wolff, which showed plating that needed to be replaced over the ship's entire length when proper repairs began, meaning the repairs would not be economical.

This, coupled with the central turbine engine (which ran the central propeller) not being able to run, and the ship listing to port could indicate that the damage was much worse than admitted. The ultimate piece of damage to Olympic, if all of these were true and a result of the Hawke collision, would be that her keel was twisted: giving her a permanent list to on her port side. If she was to be properly repaired, she would have had to have had her stern and part of her keel cut off, and that portion entirely rebuilt. A job, whose cost would have sent White Star and Harland and Wolff down the tubes down the tubes in the eyes of conspiracy theorists. Thanks to the exclusive agreement that Harland and Wolff constructed ships for the White Star Line, if the latter went down the former would be short of a major client. This lack of business would have also forced Harland and Wolff to shut down, which would also have an impact on further dependent industries. If White Star and Harland and Wolff went down, it would be a little like an economic collapse. If Olympic was damaged beyond economic repair, the threat of such an economic collapse would grow too great and something would need to be done immediately.

However, there may have been a light at the end of the tunnel, in the form of the brand new Titanic being almost identical to the damaged Olympic. It's here where a darker possibility may have come into play. If Olympic was damaged beyond repair, once Titanic was completed and ready for civilian service, what if she had her identity swapped with the damaged Olympic? Only the insurance for losing a brand new ship in a freak accident on its maiden voyage would save the two companies from going down the tubes. If the insurers believed the brand new Titanic had gone through that, they would have paid in full and the two companies would be safe from financial ruin.

All linen, china and bedding were standard issue to all ships in the White Star Line fleet, bearing only the company logo. This makes these items perfectly interchangeable from ship to ship, although letterheads, menus, ships compass and bell were styled to a particular ship. But these stylized items were easily interchangeable as well. These items, along with the names on the bows and sterns, the nameplates on the lifeboats and 48 lifebelts are all that would need to be swapped over. This job could have easily been achieved using a handful of men over a weekend, and when all shipyard workers returned to work on Monday, it would seem as if nothing happened.

Insurance and Damage to Olympic

To find out if Olympic truly was damaged beyond economic repair, we need to look at the testimony of those who examined the damage after she limped back to Southampton. One of these examiners was Harry Roscoe, a naval architect who had been in the occupation for over 25 years examined Olympic on the 22nd and 23rd September and was known to have stated that the Hawke penetrated eight feet into the side of the mighty passenger ship.

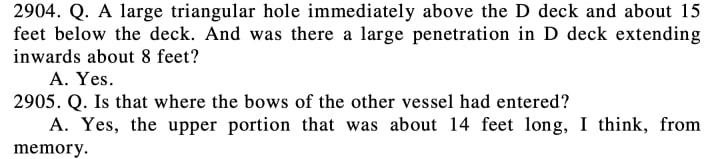

Although the Hawke did not penetrate in the flat area of Olympic's hull, where it was at its widest, eight feet is not enough to have damaged the keel. At its widest, Olympic was 92 feet wide, but in the area where it did penetrate it was roughly half of that: 46 feet. In that area, the Hawke would have had to have penetrated at least 23 feet inwards to damage the keel, 15 more than it actually did. The testimony of Robert Steele is also another factor, who tells us that the underwater ram fitted to the Hawke was not as effective as the designers had hoped.

The testimony of Robert Steele gives us an indication of how the damage to Olympic was not as severe as to consider her a write-off. If Olympic’s keel was damaged, Roscoe and Steele would surely have picked it up before they even looked inside the ship’s damaged structure. Yet, they do not express such information.

There is another factor that goes against what we have been told with regard to insurance. We have been told that Lloyd's of London refused to cover the cost of repairs, which is true, but something has been neglected: the International Mercantile Marine's insurance. In 1902, White Star Line were purchased by the International Mercantile Marine (IMM), a trust whose chairman was John Pierpont Morgan. Morgan's ambition was to monopolise the North Atlantic Passenger Market and every company competing in the market, apart from Cunard, was owned by Morgan. In the aftermath of the Hawke collision, IMM wished to claim for as much as £750,000 including lost passenger receipts, but this would only be the case if they won. They did not. The inquiry into the collision estimated that the damage to Olympic would not have cost more than $125,000 to repair. White Star Line also enjoyed the prosperity of being IMM's principal British competitor in the passenger market so IMM would be obliged to pay for the repairs. The repairs did not have exceeded their claim.

Now, we should examine the statements and "evidence" that Olympic was damaged beyond repair. Why did plating need to be replaced over her entire length? Why was only one engine running when she was returning to Belfast for repairs? Why did the patched up hull not hold fully?

To begin with, the diagram that shows plating that needed to be replaced over her entire length. If plating needed to be replaced in the bow after being struck in the stern, this would indicate that the flexing of plating throughout was caused by the ship's keel being twisted. But is this so? In June 1911, not only did Olympic collide with the Hallenbeck, but she also scraped along a pier on her bow.

This would have invariably damaged the shell plating. The central turbine engine which powered the central propeller was not running during the voyage from Southampton to Belfast, there is no dispute to that, but does it prove that the keel was damaged? The turbine engine was powered by unused fumes from the two main reciprocating engines that drove the two outer propellers, but it may have been configured in such a way that it had to be powered by both the main engines and not just one, due to the starboard engine being unusable. Not to mention the patched up hull not holding fully may explain why the engine may not have been configured to be powered by both the main engines, because the faster a ship is travelling the more stress the outer shell plating is subjected to. If the patched up hull did not hold fully with just the port side engine running, it would not have held any more if the central turbine engine was running as well.

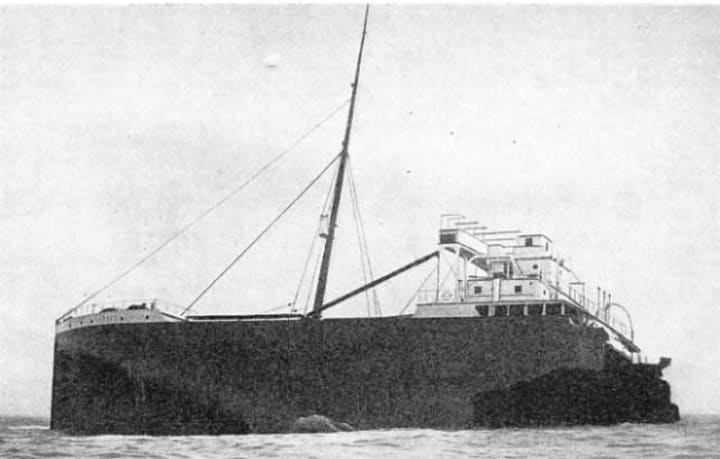

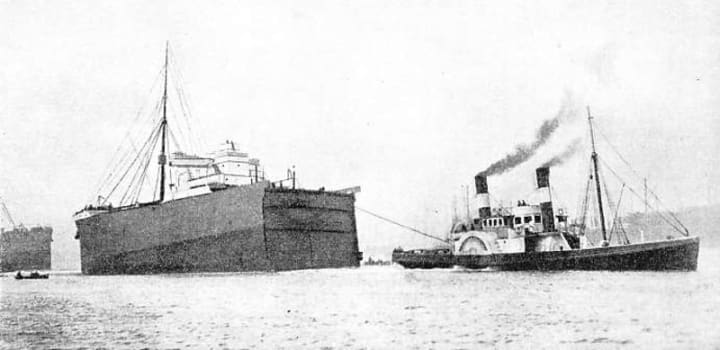

Even if Olympic's keel was damaged, she could still have been repaired. In 1907, a fellow White Star Liner the SS Suevic ran aground on the lizard peninsula in Cornwall. Her bow was badly impaled on the rocks, but her stern and midships were still intact, so her bow was severed off. Later a whole new bow section was built and fitted to the older midships and stern.

Another item of note is that if Olympic couldn’t be repaired properly without insurance money, why did she return to service before she was found to be at fault? When she was fully repaired back in Belfast, she was ready for service again by November 21st 1911. However, the inquiry into the Hawke collision took place on November 30th, and it is here where the decision to not cover the cost of repairs would have been made, not earlier. If White Star couldn’t afford to repair Olympic properly without the insurance, how did she return to service before the inquiry? Therefore, timing is not in favour of the conspiracy and the damage was not a life or death situation.

Differences Between The Two Sisters

Even if Olympic couldn't be repaired economically, would it have been possible to have switched the two sisters? At first glance, the two sisters do look exactly the same, in fact looking at photographs of the two sisters after each of their launching they do look completely identical. The A-Deck promenade is completely exposed and the windows on B-Deck are large and evenly spaced on the two sisters at the time of launching, as well as 14 portholes on the forward port side of C-Deck. Olympic retained these features during her maiden voyage and at the time of the Hawke Collision.

However, when we look at Titanic at the beginning of her short life, she is quite different in which her A-Deck promenade is half enclosed with windows, her B-Deck windows are thin and unevenly spaced and she now has 16 portholes on the forward port side of C-Deck. Why has Titanic changed so much between her launch and her maiden voyage?

Even today, a company's success depends on the needs of the customers and the employees. During Olympic's maiden voyage, J.Bruce Ismay listened to what the passengers and crew had to say. The reason why Olympic's windows on B-Deck are large and evenly spaced is that it housed an open promenade deck for her first class passengers, which was originally applied to Titanic. But during Olympic's early career, the B-Deck promenade was not popular, so it was scrapped on Titanic and replaced with 1st class suites which were fused to the side of the hull. This resulted in Titanic's B-Deck windows going from being large and evenly spaced to thin and unevenly spaced. The A-Deck promenade on Titanic had windows added because the completely open promenade on Olympic subjected her passengers to seaspray.

One such mistake that we are told by conspiracy theorists is that Olympic was originally built with 16 portholes and Titanic with 14, and mysteriously the 14 porthole configuration has found its way onto Olympic, and the 16 on Titanic, creating incontrovertible proof that the two sisters were switched. But the launch photographs prove otherwise. Titanic was given two extra portholes on C-Deck because the crew wanted more natural light in the galleys.

Now, we need to look at the minor interior differences so that we can see if it would have been possible to have switched them without someone noticing something odd going on. We need to examine the deck plans of the two ships in order to find this out.

Boat Deck

The bridge wings on the Olympic were fused with the side, whereas on Titanic they were jutted out over the side slightly. The bulwarks aft of the bridge wings were steel on Titanic and wood on Olympic. The individual quarters for the ships bridge officers were laid out dramatically differently between the Olympic and the Titanic. The wheelhouses were different, Olympic’s was curved, Titanic’s was flat. The gate to the first class promenade from the officer promenade was on the Olympic’s starboard side, whereas Titanic’s was on the port side. The Marconi wireless room was an Oceanview room on Olympic, Titanic’s was an inside room. Titanic was given first class staterooms on both sides just before the entrance to the grand staircase. Titanic was also given alcove coverings on the first class lounge area, and a staircase leading down to E Deck was included behind the deckhouse which served the third funnel. Olympic did not have alcove coverings or the staircase behind the third funnel. The stairs down to A Deck had square coverings on Titanic, on Olympic they were semi circular.

A Deck

The most prominent difference on A Deck was the addition of the windows which covered half of the first class promenade on Titanic, which was in place to shield passengers from the sea spray. This feature was never seen on Olympic throughout her entire career. To shield passengers from the wind, Titanic had two walls installed on the front end of this deck, Olympic did not have this feature at the time. Finally, two first class staterooms were added to Titanic, one on both sides. Before the disaster, Olympic did not have any first class cabins on A Deck.

Another note is that some features on the two sisters may have been physically identical, but evidence has arisen that those rooms may have had a different colour scheme. On A Deck, the first class smoking rooms on the two ships are physically identical, but there is evidence that each had a different colour scheme. Records indicate that Olympic’s smoking room ran by a green colour scheme, which was duplicated by James Cameron for the 1997 blockbuster film Titanic. However, evidence on the ocean floor seems to tell us that Titanic’s smoking room might have had a red colour scheme.

B Deck

The most prominent difference on the inside between the Olympic and the Titanic was the entire B Deck layout. The two sisters were originally built with extending promenades on B Deck, which is why at the time of launching the two sisters have large and evenly spaced windows on B Deck outdoors. But during Olympic’s pre-Titanic disaster voyages, this was not popular. Therefore, this feature was scrapped during Titanic’s fitting out and she had more expensive first class suites added, some of which became the most expensive at sea. These suites resulted in Titanic’s B deck windows going from large and evenly spaced to thin and unevenly spaced. There was also the cafe Parisian, on this deck. These suites and cafe were not seen on Olympic until 1928 because post-Titanic sinking photographs still show her with the large and evenly spaced windows on B Deck.

C-Deck

The differences get smaller as the decks go down, at the aft grand staircase on C Deck, Olympic had a large cloakroom whereas Titanic had first class suites and an extra lavatory which resulted in smaller portholes being drilled. These smaller portholes will come under further examination when we visit the wreck.

D-Deck

The first class entrances on D Deck were different. Titanic’s had extra alcoves and pillars between the elevator lobby and reception room. Olympic did not have these alcoves or pillars. It is also known that the ceiling was also decorated differently between the two sisters at this location.

F-Deck

The cooling room on F Deck was laid out differently between the two sisters. Titanic’s shampoo rooms were larger and fused with the side, Olympic’s were smaller and not fused to the side. Titanic seems to have lost one of its electric bathrooms, and the Turkish bath layout was different. Titanic also seems to have been given a clothes pressing room, and according to plans, if Olympic had one it was in a different location.

G-Deck

The central difference on G Deck is that, although they seem to be the same in terms of shape and area, the large dormitories on Olympic have been changed to large numbers of individual cabins for single male steerage passengers on Titanic.

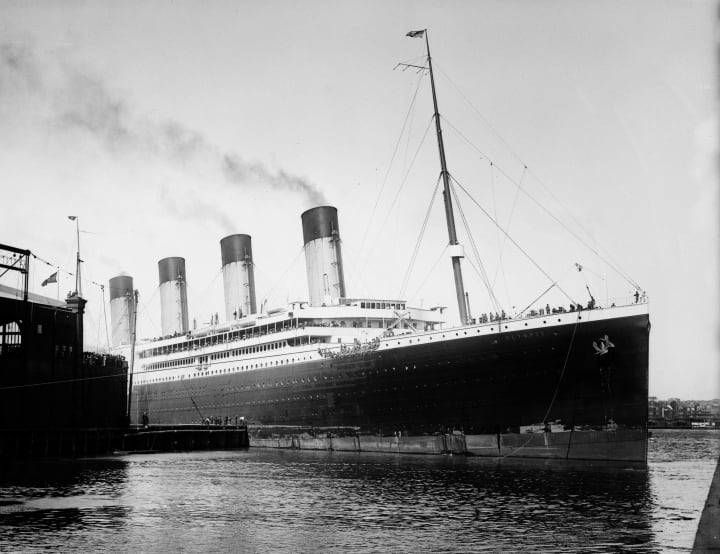

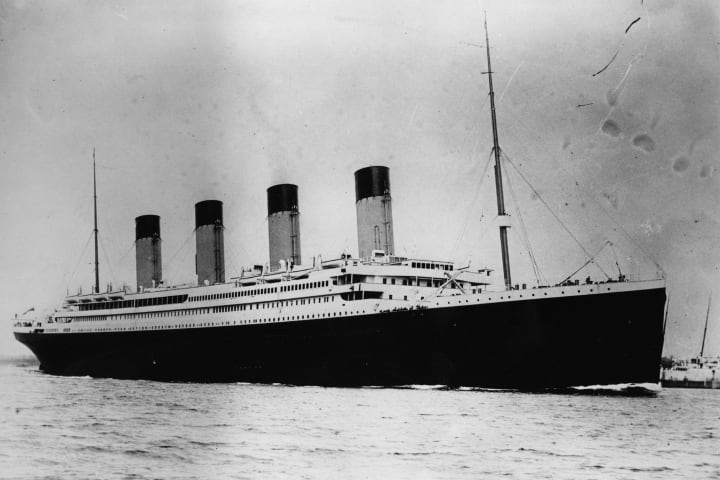

It should also be noted that there is only one ever film clip of the genuine Titanic, which is featured below. After the sinking there was a sensational demand for images, leaving journalists, newspapers and writers with no option but to use photographs of Olympic as the Titanic. Here we can see photographs labelled as the Titanic, but in fact they are of the Olympic. Olympic had her entire A-Deck promenade completely open throughout her career and was never changed. Therefore, if one claims to have a photograph of the Titanic, the feature to confirm this is the A-Deck promenade: completely open for Olympic, half enclosed for Titanic. Another piece is this film of Olympic, which is commonly used as the Titanic. The filmmaker has scratched out the names on the backs of tugboats because this clip was filmed in New York, the city the Titanic never reached.

- Fig 37

We can see that there were too many structural differences between the two sisters to have switched them without someone noticing something odd going on. Switching the two ships could never have been accomplished with only a handful of men over a weekend, it would have taken a lot of time. Olympic and Titanic took around seven and ten months each to fit out, Titanic even longer due to the differences in structural design indicated on the final deck plans, the most prominent being the different B-Deck layout. The new B-Deck layout was even under construction before the Hawke collision.

If the two sisters were to be switched, they would have to be laid up together at Harland and Wolff under an impression that they were being remodelled together to the outside world, while all employees would be tasked with switching the two ships over the seven to ten months. The two sisters were never seen together in Belfast for that long, the final time being at the beginning of March 1912.

400 vs 401

Although there were completely identical features on the two sisters, there needed to be something to distinct features from one another. To achieve this, each piece of decoration for the two sisters were marked with their build numbers: 400 for Olympic and 401 for Titanic. If an item was designated to the Titanic, it would bare the number 401, if designated for Olympic, it would bare 400.

Olympic was scrapped in 1935, in the aftermath of her scrapping many of her fixtures and fittings were auctioned off to companies and collector alike. The White Swan Hotel in Alnwick, Northumberland purchased many of the features from Olympic to furnish its luxurious interiors. Some of the balustrades from her iconic grand staircase (identical to Titanic's) furnish its stairs. In addition, the wooden panelling and marble fireplace from Olympic's 1st class lounge adorn the hotel's dining room. It has however, been confirmed that this wooden panelling has 400 inscribed onto parts of it, Olympic's yard number. All items recovered from the wreck are inscribed with the number 401, the Titanic's yard number.

If the two sisters were switched, the wooden panelling in the White Swan Hotel would be inscribed with 401, and items from the wreck with 400. But as we can see, this is NOT the case.

One item of significance is one of the propellers on the two ships. On February 24th, 1912, Olympic was making her way back to Southampton from New York where she suddenly struck an underwater object, losing a starboard propeller blade in the process, as well as shock-loading her starboard engine. By March 2nd, 1912 she was in Harland and Wolff undergoing repairs, it's here where we are told that the starboard propeller designated to the Titanic (distinctively having the Titanic's build number 401 stamped onto each of its blades), was put on Olympic to speed up repairs and was never given back. This claim will come under further investigation when we exmaine the wreck.

It is actually at this point where we are told that the switch happened, because the replacing of the propeller blade would only have taken a few hours. However, Olympic was in Belfast and out of service for five days. But they only use the replacing of the propeller blade, to explain that this is when the switch happened. But conspiracy theorists don't mention the checking/repairing of the shock-loaded engines. It should also be noted that in January 1912, Olympic was damaged in a storm where she had one of her main hatches and some railings dislodged and some loosened rivets below the waterline. Following this, a seam on Titanic was changed to prevent the damage to Olympic from repeating itself on her. All of these could have been happening aboard Olympic during this time, explaining why she was in Belfast for a week. Not to mention, she also grounded on submerged rocks during low tides in the River Lagan.

Keeping The Switch Secret

Even if Olympic and Titanic *were* completely identical and could be switched by only a handful of men over a weekend, it still would not have been possible for a secret of that calibre to stay hidden. The men who would have been tasked with switching the ships naturally would want paying to do the job, and they naturally would have been bribed to keep quiet. If someone was involved in a task of switching the two ships and one of them sunk, becoming the deadliest single shipwreck ever recorded, they surely would not have been able to keep a secret like that to themselves all the way to their deathbeds, even if they were paid to do both the job and stay quiet. Not to mention, the extra income would have aroused suspicions among their families, wondering where from and for what the extra income was earned for. Even though at the time employees had no position to question their superiors in the workplace, they would never have been able to keep a secret to themselves until they died.

One man, Patrick James Fenton, referred to by everyone as "Paddy The Pig" claimed that he was a crewman aboard the Titanic down in the boiler rooms. He claimed later in life, while living in Australia, that he heard rumors among the fellow stokers that the two sisters had been switched and that it was covered up. However, this person who called himself Paddy The Pig, was never on the Titanic at all. Her crew lists confirm this. Although this character, Paddy The Pig, was never on the Titanic, his story does reflect the human inability to keep such a secret to himself all the way to his deathbed, even if he was paid to keep quiet. In 2004, John Parkinson, whose father worked on building the two ships and was perhaps the last man alive to have ever seen the Titanic to remember the experience, confirmed that there were rumours that the two ships had been switched. If John Parkinson's father had known about the switch and was paid to keep quiet, he clearly could not have kept it to his deathbed or else John would have known.

Not to mention, Olympic and Titanic were so big, they could be seen all over the Belfast skyline. So if they were to be switched, the entirety of Belfast would have easily been able to see what was happening and questioned Harland and Wolff. What if someone high up in social status saw what was happening and reported the two ships being switched? How would Harland and Wolff keep the entire city of Belfast, one of the largest cities in the world, quiet?

Sea Trials

Olympic’s sea trials lasted two full days, and included strenuous testing manoeuvres. But Titanic’s lasted only one day, and according to conspiracy theorists, did not include strenuous manoeuvres and was over in time for lunch. Is there another explanation? Titanic's sea trails were scheduled to take place on April 1st and 2nd 1912, but heavy winds on April 1st meant it was too risky to conduct them on that day. Therefore, all tests on Titanic were conducted on April 2nd and did include strenuous testing manoeuvres. Several stop/start tests were carried out, where she drifted to a stop. Several turning tests were carried out, using the rudder and propellers only, several helm-hard-over tests to see how quickly she could turn, a crash stop test in which she stopped in just 850 yards and several twisting tests from port to starboard. All of these do describe strenuous manoeuvres, and these could not have been concluded in time for lunch, after all, the trials ended at 7pm, not midday.

The reason why we are told that Titanic's sea trails were concluded by lunch time, is down to the fact that the ships had already been switched at that point. They were testing the old damaged ship disguised as the new one which had never been tested at all. They also tell us that the patched up hull in the Olympic's bow was fragile, and couldn't handle the stresses of high speeds.

CONTINUED ON PART TWO...

See Bibliography for sources...

About the Creator

Luke Milner

Writer, Maritime History, Travel, and Film enthusiast. Here you can find my many articles on such topics, and learn more. You may also find my recommendations for films, and traveling.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.