THE OTHER GREAT FIRE OF LONDON

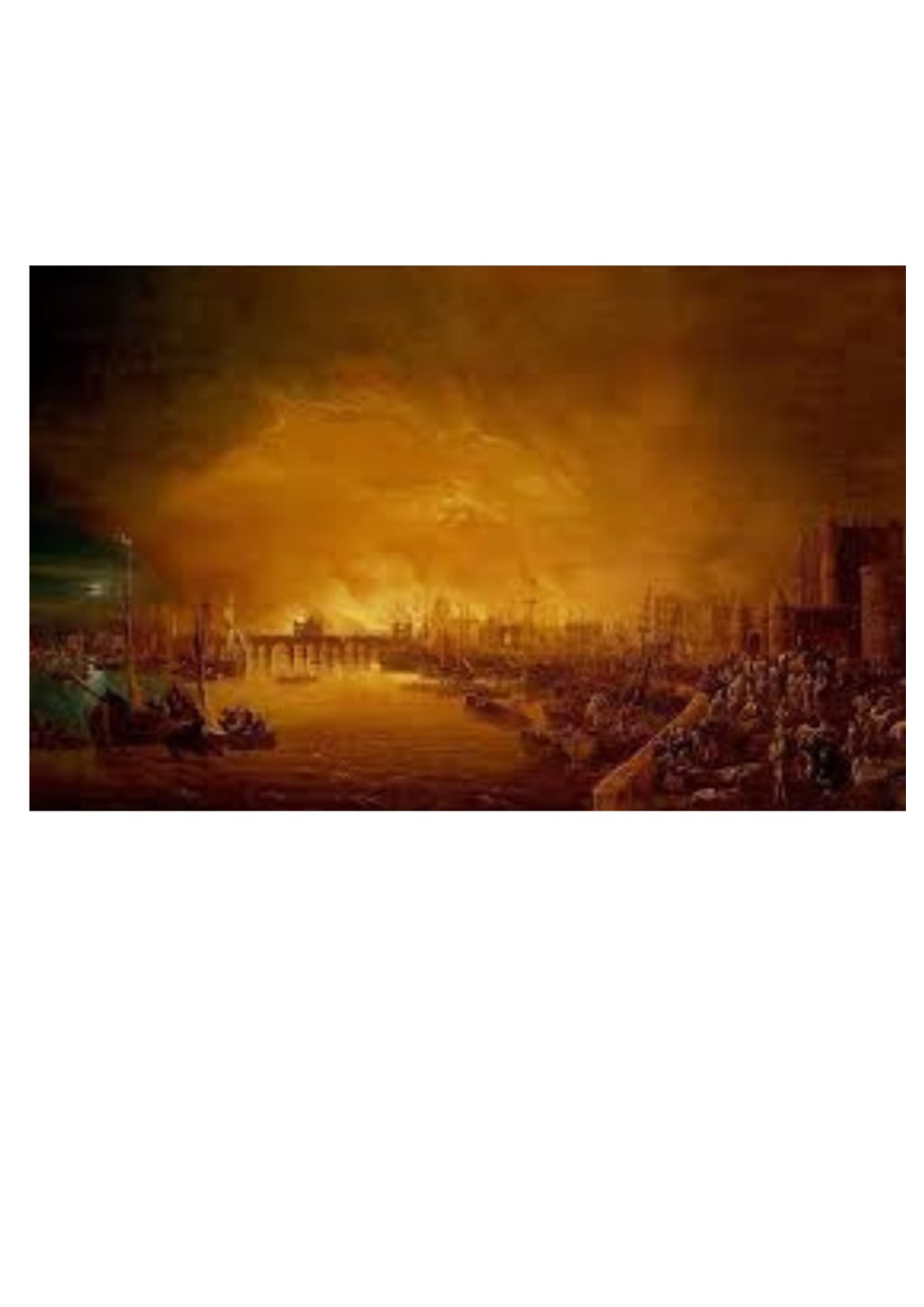

The water reflected the towering flames of the burning ships, till the very Thames itself seemed on fire.

The Tooley Street fire has been described as the worst London fire since the Great Fire of London. The fire began on Saturday, 22nd June 1861, at Cotton’s Wharf, where many warehouses were situated. At 5 p.m. workers in the warehouse along the river by London Bridge, near Tooley Street, were preparing for the Sunday shutdown. Almost everyone had left for the Sunday shutdown when a fire began.

The cause of the fire is believed to have been spontaneous combustion, and some suggest that someone smoking in the wharves may have started the fire. Whilst Cotton’s Wharf was classed as good for fire protection, the surrounding buildings were less well protected, which enabled the fire to spread quickly.

Cotton’s Wharf was around 100 by 50 feet and contained approximately 5,000 tons of rice, 10,000 barrels of tallow, 1,000 tons of hemp, 1,100 tons of jute, 3,000 tons of sugar and 18,000 bales of cotton at the time of the fire. Unsafe jute and hemp storage in Cotton’s Wharf and nearby wharves helped spread the fire.

Later that evening, the fire stretched from London Bridge to Custom House. Properties that were destroyed included offices, a steamer, four sailing boats, and lots of barges. Tallow and oil t poured in from the wharves and flowed out blazing on the river. Five men in a small boat collecting tallow floating on the river were burnt to death when their boat caught fire. Several men working in the warehouses fell into the river and drowned.

The river fire engine could not draw water from the River Thames as it was low tide and so the river was too shallow. The fire was so massive that it forced the fire engines to retreat. The firefighters were also inhibited when the spice warehouses caught fire and dispersed spices into the air.

Without pause, the flames then leapt the walls, engulfing other wharves. There was fire north, south, east, and west, fire everywhere; lurid red flames in dense masses rose and floated like clouds of fire over the doomed wharves.

From the opposite side of the river, it appeared like a volcano, throwing up flames, reddening the sky, and illuminating the public buildings with the shade of an unnatural-looking autumnal sunset.

In his diary, Arthur Munby described the scene as: For near a quarter of a mile, the south bank of the Thames was on fire: a long line of what had been warehouses, their roofs and fronts all gone; and the tall ghastly sidewalls, white with heat, standing, or rather tottering, side by side amid a massive space of red and black ruin, which sent up massive sheets of flame a hundred feet high.

If you had been in London on that Saturday night, no doubt you would have made your way, with thousands of other sightseers, to watch the fire burn. It is estimated over 30,000 spectators came from all over the city. Omnibuses were packed, and Men were struggling for places on them, offering three and four times the fare for standing room on the roofs, to cross London Bridge. Every inch of space on London Bridge was crowded with thousands and thousands of excited faces.

Around 7 30 p.m., a section of a warehouse collapsed on top of James Braidwood, the London Fire Engine Establishment superintendent, killing him. On his way to the aid of a colleague, one who’d gashed his hand, he gave help. Braidwood removed his red silk Paisley neck silk, to use as a bandage to bind the man’s bleeding hand. He was moving to the river with Peter Scott, one of his officers, when a warehouse wall bulged and cracked and gave way completely. It fell with a deafening noise, killing both Braidwood and the officer instantly. Because of the flames’ intensity, his body wasn’t recovered for three days, yet ironically, was untouched by fire.

They buried James Braidwood at Abney Park Cemetery on 29 June 1861, alongside his stepson, a firefighter who died five years earlier in the line of duty. The cost of the fire led to the founding of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade.

The procession for the funeral to Abney Park Cemetery Stoke Newington was over a mile long. Shops were shut and crowds lined the route. The epaulettes from his tunic were removed and were given to other firefighters. They are part of the museum’s collection today.

It took nearly two weeks to put out the fire the and costs were an estimated £2 million – mainly because of the warehouse’s contents. That would be over £160 million in today’s money.

About the Creator

Paul Asling

I share a special love for London, both new and old. I began writing fiction at 40, with most of my books and stories set in London.

MY WRITING WILL MAKE YOU LAUGH, CRY, AND HAVE YOU GRIPPED THROUGHOUT.

paulaslingauthor.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.