The Dark Fascination of Ilse Koch: The Story of the Witch of Buchenwald

Unraveling the Enigmatic Legacy of Ilse Koch: The Witch of Buchenwald

The woman, who unleashed all her cruelty in that place where some 56,000 prisoners were murdered - according to figures provided by the Holocaust Museum - was indicted for war crimes at the end of the world conflict and sentenced to life imprisonment. In 1967, she committed suicide in prison. She would go down in history as one of the most bloodthirsty and ferocious women in the already terrifying Nazi criminal machine.

childhood and early working life

Margarete Ilse Köhler - her maiden name - was born on September 22, 1906 into a middle-class family in the German town of Dresden (Saxony). The daughter of Anna and Emil, a farmer who later became a factory manager, Ilse behaved like any other girl of her age. Quiet, responsible and well-behaved, she became very popular among her schoolmates.

Nothing foretold that she would later become a murderer. In fact, little is known about her upbringing and how she might have been treated or mistreated by her parents.

At the age of fifteen she left school to start working. First she worked in a factory, but soon after she ended up in a bookstore as a sales clerk. It was in this last job where she began her interest in the Nazi Party and where she also met members of the SS. In fact, her overwhelming and charming personality helped her, among other things, to become a secretary and member of the NSDAP in 1932.

Some time later, Heinrich Himmler himself, head of the SS and the Gestapo, chose the young Ilse as the wife of one of his chief assistants, Karl Koch, colonel of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. In 1936 they married and in 1939 they moved to Buchenwald, one of the largest Nazi killing centers. It was here that the most macabre atrocities of the Koch couple took place.

The field of horrors

Nearly 250,000 prisoners passed through Buchenwald, of whom it is estimated that more than 25 percent were murdered. There were no gas chambers in Buchenwald, but deaths from starvation, abuses by the guards and arbitrary actions by the authorities were daily and massive.

Koch and his wife liked to live well. They built themselves a mansion that they furnished with the best of what they had produced from the looting of their victims. The couple's megalomania had a striking example in the zoo they set up inside the concentration camp facilities. They had exotic species brought in from all over the world.

Ilse Koch was much more than the wife of the camp commandant. The wives of the commandants did not usually leave their homes, they were housewives who devoted themselves to raising their children and creating the illusion of normalcy in their children's lives. But Ilse was different. Her place was not passive. She made her presence felt. She strolled her energetic arrogance and red hair around every corner and gave orders constantly. Everyone feared her. And there were reasons. She was merciless.

In the subsequent trials, some witnesses also described her as a nymphomaniac, that her need for sex was constant. And that Dantesque orgies organized by her took place in the mansion, and that she was in charge of recruiting participants in the neighboring village and among the officers and soldiers in charge of her husband and their wives. But these testimonies not only spoke of her sexual activities in her home - not criminal for the most part, except in the cases of those who participated under duress - but described how Ilse forced the detainees to have sex only for her to assist as a witness and satisfy her vouyeristic inclinations, or to dispel her boredom. They also said that those who could not perform sexually were ridiculed and then beaten. No one could look her in the eye or contradict her. Whoever did so was shot on the spot. At other times she would grope them or expose their breasts, and whoever was not aroused was punished.

She herself was in charge of whipping and subjecting to other torments those detainees who did not comply with her whims. She used to carry around her waist a kind of truncheon with several razor blades attached to the end of it. It is said that one of his favorite games was to lock about twenty prisoners in a corral and release several wild dogs inside. While men and women ran for their lives and received fatal bites, Ilse's laughter could be heard dozens of meters away.

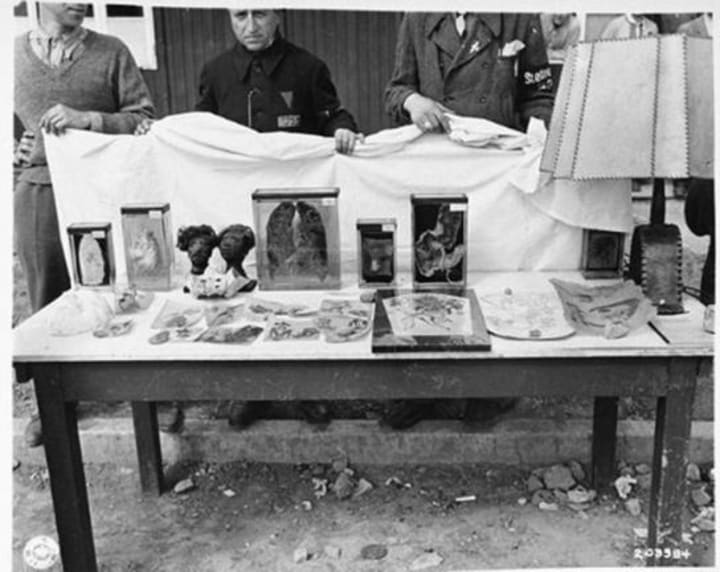

There were several witnesses who stated that Ilse had many detainees executed with precise orders not to injure certain areas of their skin so that she could keep those tattooed fragments that had caught her attention.

One of her lovers was Waldemar Hoven, the doctor in charge of the medical research department at Buchenwald. Ilse and Hoven made the new arrivals undress. Those with the most striking tattoos were taken out of the line and shot (with a shot in the back of the head so as not to damage the skin).

In Buchenwald several human skin plates with tattoos were found. There were also leather lampshades, but it could not be reliably established that they were derived from the remains of prisoners. In the trials to which she was subjected, Ilse was always acquitted of these charges for lack of evidence.

The overflow of the Koch couple in Buchenwald was such that it even provoked rejection within the Nazi regime. The luxury with which they lived had become an obligatory comment among high-ranking officers. The death of two Buchenwald doctors led to an internal investigation. Karl-Otto Koch claimed that they were infiltrators and that once discovered they had tried to flee. In that escape they were hit by shots fired by his men. The investigation determined that the cause had been different: the doctors had treated Koch for syphilis and he had eliminated them so that his secret would not be known.

But neither this episode, nor his thefts, nor his other murders and abuses ended the couple's career. Himmler, their protector, sent Koch to take over Majdanek. He needed someone ruthless there.

But Ilse continued to live in her mansion in Buchenwald and to behave as if there was no law there except her whims. Her husband also fell into disgrace in Majdanek.

"I'm guilty! I'm a sinner!"

A few months later, in an attempt to cover up a mass escape of Soviet POWs from the authorities, Koch ordered a massacre that only served to draw attention to his lack of expertise and control over his actions. He was displaced and sent to an administrative post in Berlin. In time he was once again sent to Buchenwald. On his return he behaved in the same manner as always. His end came with a visit from his protector, Himmler. The hierarch found that while Germany was crumbling, the Kochs continued to live in luxury. It was easy to accuse them of various crimes, embezzlement, theft, and to find evidence. Even the imminent Nazi defeat did not save Koch. He was tried in the concentration camp itself, sentenced to death and executed in early April 1945, only a week before the Allies liberated Buchenwald. Ilse was not convicted (it is said that the acquittal came after she faked a nervous breakdown before the judges) and managed to escape before the arrival of the enemy. She took refuge in the western part of Berlin, far from the reach of the Soviets.

When she was arrested after the war, the evidence of the atrocities committed during her years in Buchenwald covered up for the magistrates. She was tried in the so-called Dachau trials along with other women. She was sentenced to life imprisonment. She was spared the death penalty because she was pregnant. The father was unknown, and her accusers suspected that she had become pregnant to avoid the gallows. As soon as the baby, a boy, was born, he was given up for adoption.

However, some time later, the American general Lucius Clay, governor of the American Zone in Germany, reduced her sentence to 4 years in prison. But in 1951 she was again arrested and tried once more. This time the charges focused on acts committed against German citizens.

The trial generated peculiar attention. Although the story of the barbarity had already been heard several times at that point, the trial of Ilse Koch added new elements. The accused was a woman, the sexual components, the sadism and the suspicions of the use of the skins of the murdered. Someone even held her responsible for at least 5,000 of the 56,000 deaths that took place in those years in Buchenwald.

The Nazi doctors in the camp were very interested in human skin. Ilse would motivate them all the time to go on with their tests and procedures. They would remove the skin, subject it to a chemical process and put it out to dry in the sun. When you walked by you could see them, a Czech doctor sent to Buchenwald by the Gestapo testified at the trial. These skins were used to make gloves, wallets, screens and even to bind books. Those with a particular tattoo were more highly valued. There was one more detail: these skin remains could not have come from Germans. So the victims were mostly Soviets, Poles and Gypsies. And since the skin had to be in good condition, the degraded bodies of those who had long since been crammed into the lager were of no use to them either. Sometimes Ilse ordered the killing of new arrivals because their lushness would provide optimal skin.

January 15, 1951. In the courtroom the tension has a physical presence. She, the main defendant, is not there. The judges allowed her to remain in her cell. It seemed the only possible way to end the trial. Her screams, nervous breakdowns and fainting spells - which no one could determine if they were real or faked - interrupted the hearings several times. Once, in the middle of a survivor's story, Ilse Koch stood up and shouted, "Yes, I am guilty! I am responsible for everything! I am a sinner!" The audience also screamed in horror amidst the testimonies pointing to her as responsible for a variety of unimaginable atrocities. The reading of the sentence was brief. The sentence was one of the worst possible: life imprisonment. But the spectators inside the courtroom and those waiting in the street reacted with indignation and there were fears that a riot would start. They wanted the death penalty and that among the facts that the court found proven were the lampshades made of human skin and his fondness for collecting pieces of tattooed human skin

His last years

The days of her last years are monotonous, just like themselves. She is detained. She is alone. An official defender makes periodic, gray and hopeless pleas for her release. They both know that the requests will not succeed. Her behavior is increasingly erratic. Even convicts convicted of heinous crimes look down on her.

Of the three children (two men and a woman) she had with Koch, only two survive. The eldest committed suicide because he could not bear the shame of his parents' crimes. None of them visit her. No one comes near her. Only one afternoon a young man pays her a surprise visit. The first visit since she has been detained. She can't imagine who it could be. She does not recognize him, although she discovers a familiar look on his face. The meeting is silent. They look at each other without speaking for a few minutes. She gets nervous. She thinks that her worst nightmare, what torments her and what she dreams about every night, has come true: a relative of one of her victims has come to take revenge. She starts screaming and tries to escape from the small room. The guards rush to control her. The young man, little more than a boy, reaches out and touches her shoulder awkwardly, a wary caress. "I am Uwe, your son."

The son who had been given up for adoption as soon as he was born looked for his biological mother. He continued to visit her with some regularity. He needed to know her, he needed to understand. He believed that by looking into those wild eyes he would learn the truth. Ilse, his mother, had not been there for some time. Her days passed between the most absolute mutism, bursts of guilt, fits of anger, delusions and requests for rescue from the imaginary attack of her persecutors.

Ilse's screams drove the other inmates crazy. They started at night but then appeared at any time of the day. The woman was convinced that a commando group of lager survivors and relatives of the murdered were storming the prison to kill her. The persecution mania only grew.

On September 1, 1967, Ilse Koch tied her bed sheets and a threadbare coat to the top of the bars of her cell and hanged herself. In a few weeks she would have been 61 years old. She left behind a letter that read: "There is no other way out for me. death is the only salvation".

For decades, her son Uwe sought to revisit the past and tried, in vain, to clear his mother's name. Despite his efforts, Ilse Koch, his mother, will always be "the Bitch of Buchenwald".

About the Creator

diego michel

I am a writer and I love writing

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.