The First Map of Low-Frequency Gravitational Waves: Listening to the Universe’s Deepest Echoes

Space

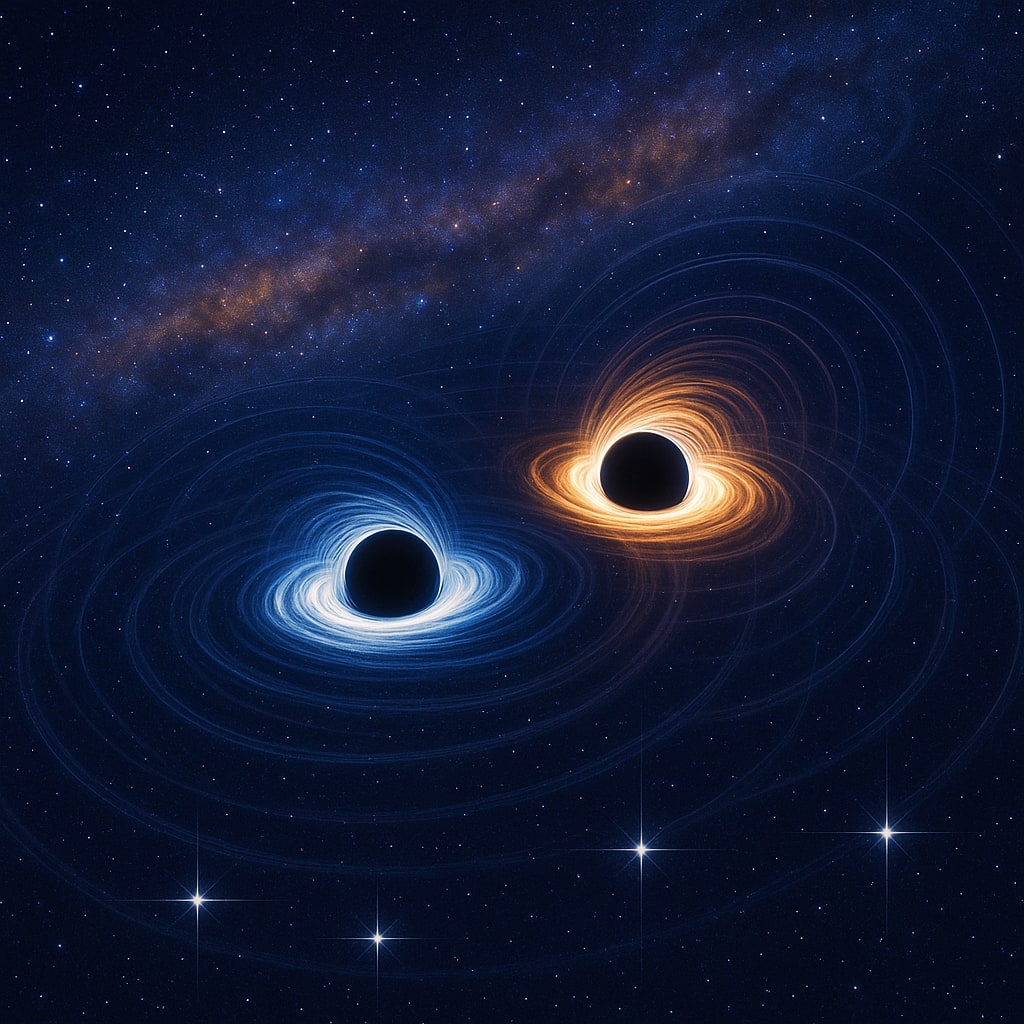

Astronomy has always been about looking deeper into space, but today, scientists are learning to listen as well. The cosmos does not only shine; it hums, vibrates, and resonates with invisible waves. And in 2025, for the first time, astronomers have created a map of low-frequency gravitational waves—a faint but persistent background signal produced by the slow, titanic mergers of supermassive black holes across the Universe.

This groundbreaking achievement comes from a collaboration between the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves (NANOGrav) and European radio observatories. Their work offers humanity a new cosmic tool, comparable in significance to the discovery of the cosmic microwave background in the mid-20th century. Instead of a snapshot of light from the infant Universe, this is a map of ripples in spacetime itself.

From Flashes to a Cosmic Hum

Most people first heard about gravitational waves in 2015, when the LIGO and Virgo observatories announced the detection of high-frequency ripples in spacetime. Those signals came from cataclysmic collisions between stellar-mass black holes and neutron stars. They lasted just fractions of a second but carried more power than all the stars in the Universe shining together.

Low-frequency gravitational waves, however, are a different story. These signals are stretched across thousands to millions of years, far too slow for LIGO’s laser detectors. Their origin lies in the most massive and dramatic objects we know: supermassive black holes, millions or even billions of times the mass of the Sun. When galaxies collide, their central black holes begin a cosmic dance, spiraling closer together over eons before eventually merging. Each pair contributes a deep “note” to the symphony of the Universe, forming a background hum that fills the cosmos.

For decades, this background was predicted but remained elusive—until now.

How Do You Listen to Such a Signal?

Since laser interferometers cannot capture such slow oscillations, scientists needed a different strategy. They turned to pulsars, the lighthouses of the Universe.

Pulsars are rapidly rotating neutron stars that emit beams of radio waves with extraordinary regularity, like a perfectly ticking cosmic clock. By monitoring dozens of pulsars scattered across the sky, astronomers can detect tiny deviations in their rhythm. When a gravitational wave passes between us and a pulsar, it subtly stretches or squeezes spacetime, making the pulse arrive a fraction of a second early or late.

Over the past decade, NANOGrav and European partners carefully monitored a network of these pulsars. After collecting and comparing enormous amounts of data, they found a consistent pattern of distortions—a signal that cannot be explained by random noise or measurement error. The only plausible explanation is the long-awaited background of low-frequency gravitational waves.

A Map Unlike Any Other

The result of this research is the first map of low-frequency gravitational waves. Unlike an astronomical photograph of stars or galaxies, this map resembles a heat chart, highlighting regions of spacetime where the gravitational hum is most pronounced.

It represents more than just data; it’s a new way of experiencing the Universe. Telescopes allow us to see, but this map lets us hear the slow, rumbling song of merging black holes. For the first time, scientists can visualize not only what the cosmos looks like, but also how it vibrates.

Why It Matters

The implications of this discovery reach far beyond the novelty of making a “gravitational wave map.”

Tracing Galactic History. Each supermassive black hole merger is tied to the collision of galaxies. By studying the background hum, astronomers can reconstruct the history of galactic growth and interaction across billions of years.

Understanding Extreme Physics. These maps provide insight into how the most massive black holes in existence evolve and interact, shedding light on dynamics that can never be recreated in a laboratory.

Clues from the Early Universe. Some theories suggest that hidden within this background may be signals from the Universe’s earliest moments—phase transitions shortly after the Big Bang, or even exotic phenomena like cosmic strings. If true, gravitational waves could become a direct probe of physics beyond the reach of particle accelerators.

The Dawn of Gravitational Wave Cartography

This is just the beginning. In the coming years, the picture will sharpen as more pulsars are observed, more data are analyzed, and more international collaborations emerge. On the horizon is LISA (Laser Interferometer Space Antenna), a planned space-based detector that will join the search in the 2030s. LISA will open an even broader frequency range, offering unprecedented precision in mapping the Universe’s deepest vibrations.

For now, though, we stand at a turning point. Humanity has gone from speculating about gravitational waves, to detecting them, to mapping their background hum. We are no longer limited to seeing the cosmos—we are learning to hear it.

A Universe That Sings

Imagine stepping outside on a clear night. For millennia, people have marveled at the sight of the stars, unaware that all around them the very fabric of reality was ringing with waves too deep and slow to perceive. Now, with the first map of low-frequency gravitational waves, we finally have the instrument to hear this cosmic symphony.

The Universe is not silent. It sings in a chorus conducted by merging supermassive black holes, and for the first time, humanity has begun to chart its song.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.