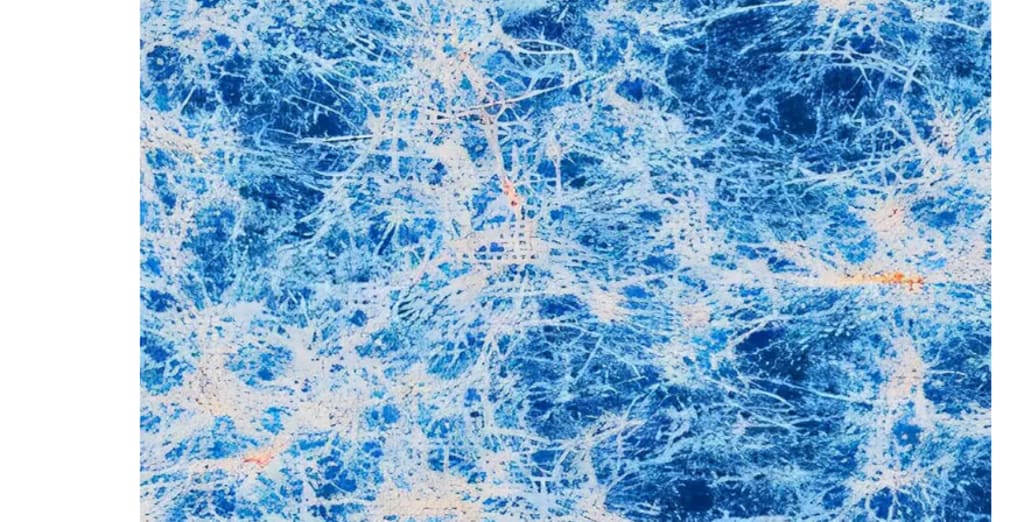

The 'cosmic web,' the universe's secret roads, is seen for the first time by astronomers.

Researchers have captured the slim strands connecting galaxies and pursued them for about 3 million light years.

Space isn't empty. Even the greatest telescopes have trouble seeing the minuscule strands of matter that are woven throughout it. This enormous network is known to astronomers as the cosmic web. It is the unseen framework that holds galaxies in place and directs their expansion.

The best filaments on the web were previously limited to educated assumptions and computer models. One filament has now been taken out of theory and put right in front of us by a new observation.

The sightings come from a sky stain that burns two old quasars over 11 billion light years. Your glow backlight is the weak hydrogen bridge that spreads between them. Recognizing the bridge required the lessons and measures of hundreds of telescopes developed for forensic astronomy.

The international team, under the direction of the University of Milan, shed new light on, worked together with the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics to focus on this twin quasar. All galaxies have exceptional black holes, both of which sit in an era when the universe was about 2 billion years ago.

Researchers have captured the slim strands connecting galaxies and pursued them for about 3 million light years. They were based on spectroscopic probes or equipped with several units mounted on the Southern European Observatory in Chile.

The Muse collects the spectrum of each pixel in the field of view, allowing astronomers to separate the weak hydrogen emission of the filament from background noise.

Light takes time to travel along the young galaxy, so the photos capture the universe of young people. Weak filaments indicate gases flowing along the gravitational stream towards the outer regions of the galaxy, which refers to the galactic medium.

Future stars are made of this flow as their basic material. Observing it directly supports a fundamental tenet of so-called cold dark matter theories: instead of consuming individual clouds, galaxies expand by sucking gas along web-like funnels.

According to cold dark matter, over 85% of the mass in the cosmos is undetectable to standard telescopes. The density of the surrounding dark matter determines brightness. Estimates of the amount of ordinary gas that the dark component corrals are improved by comparing observations to models.

Getting equipped with MUSE

Davide Tornotti, Ph.D. candidate at the University of Milano-Bicocca and study leader, says, "We were able to precisely characterise its shape by capturing the faint light emitted by this filament, which travelled for just under 12 billion years to reach Earth."

"For the first time, we were able to use direct measurements to trace the boundary between the material found in the cosmic web and the gas that lives in galaxies."

The investigation tested the boundaries of MUSE. The equipment acquired over 100 hours of data on the same celestial turf throughout multiple observing seasons.

The researchers were able to trace brightness fluctuations along the filament and compare them pixel by pixel with predictions from the supercomputer, thanks to the image that was created by that prolonged look.

From modelling to the skies

Gravity was shown in those Max Planck Institute simulations as the architect who assembles dark matter into an infinite framework. Then, like morning mist falling into valleys, ordinary gas travels along the scaffold.

The agreement was remarkable when the scientists superimposed the artificial filament on top of the one they had seen. The glow's fine features matched the model's knots, indicating that the computers had faithfully modelled nature's architecture.

Additionally, the match provides a reality check for ideas that modify the behaviour of dark matter. The filament brightness and density must now be replicated by any other model without disrupting the larger network. This makes a single high-definition strand an essential metric for assessing cosmic structure.

How galaxies are fed by filaments

Gas moving along filaments changes the appearance of galaxies in addition to ending up in stars. Streams supply their discs with new hydrogen, which powers chemical enrichment, spiral arms, and radiation bursts.

Galaxies would fade after running out of gas in a few hundred million years if there were no consistent influx. The new image demonstrates that the influx occurs on a large scale and early.

Additionally, it shows a clear separation between intergalactic gas and material that is affixed to galaxies. The reason why certain galaxies continue to create stars while others cease and turn red can be explained by identifying that border.

Street for Space Web

"We are keen to observe this direct high-resolution space filament. But as Bavarian people say, it is " "We will gather more data to reveal a comprehensive vision of how the gas is wrapped, revealing more structures.

Future research will benefit from next-generation instruments such as telescope-planned high-resolution spectrometers. Further investigations are looking for other filaments. It outlines the complete map of the universe's scaffolding and reveals how often these sparkling threads are.

With the initial detection, all new chains tighten the dark matter limitations of physics and galactic development.

At this point, the filament stands between two fiery quasars as the sharpest image of the network holding the cosmos together. It shows gases that move along the spider silk highway and feed the galaxy during its formative period.

It is even more important that patient observations can illuminate the structure after the range. Astronomers stack additional strands, creating clearer portraits of our universe's hidden framework.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.