Not how you might think, a black hole is starving its galaxy to death.

Sadly, the galaxy perished too soon due to a black hole.

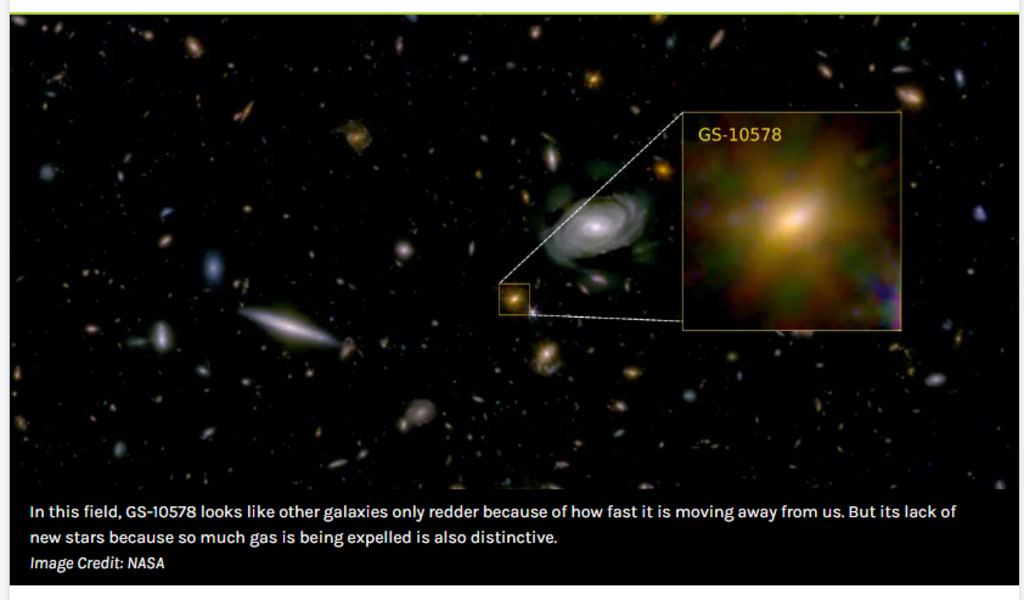

The JWST's observation of a galaxy has verified the theory that certain supermassive black holes have the ability to destroy their host galaxy. The galaxy under consideration orbits the Milky Way, but it is traveling in a completely other direction. There is another way to do this insider murder than you might think since the black hole is devouring so much gas that not enough is left behind to generate stars.

Two billion years old is hardly a child by cosmological standards, and far too young for a galaxy to perish. Large galaxies with only a few billion years left on their clock should be able to look forward to a fruitful existence, but smaller galaxies might finish their lives at that age after being devoured by larger ones.

But in the instance of GS-10578, it isn't the case. Thanks to a brief but strong phase of star creation just over a billion years after the Big Bang, it will continue to shine for a very long time. Nevertheless, its supermassive black hole (SMBH) is to blame for it being essentially dead and unable to produce new stars.

For a variety of causes, galaxies eventually die because they run out of gas, which is needed to produce stars. Astronomers refer to this period of prospective star creation halting in galaxies as "quenching."

Dr. Francesco D'Eugenio of Cambridge University stated in a statement, "Based on earlier observations, we knew this galaxy was in a quenched state: it's not forming many stars given its size, and we expect there is a link between the black hole and the end of star formation." "Yet, before Webb, we were unable to conduct a thorough enough analysis of this galaxy to verify that connection and we were unsure of the duration of this quenched state."

It is simple for non-astronomers to picture a massive black hole at the center of a galaxy suckling all the gas inward, resembling some kind of ferocious cosmic tapeworm that expands spectacularly but leaves no fuel for star formation. But this is impossible, even for the most ravenous black holes we have seen, especially in a galaxy like GS-10578, whose mass is believed to be 200 billion Suns, 80 percent of which is already made up of stars.

Rather, the killer black hole accelerates matter to 1,000 kilometers per second (2.2 million mph), near the galactic escape velocity, which makes the galaxy vomit gas. It's more akin to a case of food illness. Although ionized gas winds produced by black holes are frequently seen, star formation has only been shown to be slowed down rather than completely stopped in these instances.

The black hole of GS-10578, however, is operating double-time, according to JWST data. At lower temperatures, the SMBH also releases considerably denser neutral material in addition to the gusts of hot but thin ionized gas that are formed. Although it is too cold to be observed directly, its higher density has a significantly greater impact on the mass balance of the host galaxy. We only know what is going on because the JWST was able to detect the silhouette formed when black gas clouds obscure more distant galaxies.

The JWST observations yielded an adequate amount of gas to explain GS-10578's star formation cessation.

"It's the culprit," D'Eugenio declared. "By severing the galaxy's supply of "food," which is necessary for the formation of new stars, the black hole is destroying this galaxy and keeping it dormant."

But this catastrophe is not just evidence that black holes can destroy their host galaxy in this manner. GS-10578 reached a mass similar to the Milky Way's remarkably quickly because it is so far away that we are viewing it as though it were 2 billion years after the Big Bang. Given the star abundance, it also indicates that star creation was active until very recently; black holes began to rapidly and fatally devour stars some 400 million years ago.

Beyond demonstrating that black holes can destroy a host galaxy in this manner, there is more to this occurrence. Given its extreme distance, GS-10578 is observed as occurring two billion years after the Big Bang, indicating an exceptionally rapid ascent to a mass comparable to that of the Milky Way. Its starry sky indicates that star creation was active until very recently; beginning roughly 400 million years ago, black holes began to quickly and fatally devour stars.

Conversely, GS-10578 exhibits none of the indicators that models expected for such a catastrophic death. Rather than being destroyed by turbulence as we had predicted, its shape and the motion of its stars are conventional.

In the local universe, galaxies that are massive and include a tiny number of higher-mass stars that die faster are known as "galactic corpses." But just as it's challenging to pin down the perpetrator in a cold case, humankind arrived much too late to witness the cause of death firsthand.

Having seen a galactic murder in action, we now know one possible scenario for them, but this does not imply that all deaths have the same reason. We don't yet know if some of the victims we saw perished in this way, but an alternate idea suggests that explosions from multiple young bright stars can evacuate a galaxy's gas with comparable effects.

GS-10578 was formerly believed to be a member of the blue nugget class of galaxies, so named because of its extreme density and presence of young stars. Instead, it turns out to be a red nugget, which lacks fresh star formation but is nonetheless extremely dense.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.