New Frontiers in Space Radiation Protection: Tissue Implants and Genetic Modifications

Space

As humanity pushes further into deep space—toward permanent lunar bases, multi-year missions to Mars, and eventually interplanetary travel—one invisible threat becomes increasingly central to mission planning: radiation. Not the background radiation we face on Earth, but intense fluxes of charged particles, galactic cosmic rays, and unpredictable solar storms. Over long durations, these particles damage DNA, increase cancer risk, disrupt neurological function, and weaken cardiovascular health. Traditional shielding has reached its limits, and this has driven scientists to explore a surprisingly promising direction: biological protection from the inside out.

Over the past decade, research teams around the world have begun developing radical new strategies that combine biotechnology, genetic engineering, and human augmentation. Two approaches stand out as especially transformative: tissue-based radiation-absorbing implants and genetic modifications that enhance the human body’s natural resistance.

Tissue Implants: A Living Shield for Deep-Space Missions

While spacecraft hulls and water-filled walls remain useful, they cannot block the full spectrum of cosmic radiation without becoming prohibitively heavy. Tissue implants, by contrast, offer localized protection where it matters most—around organs that suffer the greatest radiation damage. Several cutting-edge concepts are already showing strong potential.

Melanin-Based Implants

Melanin, the pigment that gives color to human skin, hair, and eyes, also happens to be a remarkably efficient absorber of electromagnetic radiation. Certain melanin-rich fungi collected on the International Space Station have demonstrated the ability to grow faster under increased radiation, apparently using it as an energy source.

Leveraging this discovery, bioengineers are developing melanin-infused implants that can be wrapped around high-risk organs such as bone marrow, lungs, and the gastrointestinal system. In effect, these implants act as a biological buffer, intercepting harmful particles before they reach vulnerable tissues. Unlike metal shielding, melanin implants regenerate, integrate with nearby tissues, and add virtually no mass to a mission.

Hybrid Implants with Nanoparticles

Another approach involves embedding biocompatible nanoparticles inside flexible polymer scaffolds. Cerium oxide nanoparticles, for example, are extremely effective in neutralizing free radicals generated by radiation exposure. When incorporated into an implant, these particles serve as a second line of defense, reducing oxidative stress and preventing cell death.

Such implants could be strategically placed around organs most essential for long-duration missions, including the heart and central nervous system. They absorb radiation, deflect charged particles, and reduce biochemical damage at the cellular level.

Regenerative and Therapeutic Implants

Some implant concepts go further than protection and offer active tissue repair. These devices release growth factors, antioxidants, or molecules that stimulate rapid recovery after radiation-induced injury. For astronauts facing years in deep space without immediate medical support, regenerative implants could significantly extend mission safety margins.

Genetic Modifications: Engineering Radiation-Resistant Humans

If tissue implants provide a shield, genetic engineering offers a more profound solution: building radiation tolerance directly into the human genome. Although still considered experimental and ethically complex, the progress achieved so far is remarkable.

Enhanced DNA Repair Systems

Human cells already contain sophisticated mechanisms to repair DNA, but nature offers far more robust templates. The bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans famously survives radiation doses thousands of times higher than humans can tolerate. Its genome contains highly optimized DNA-repair pathways.

Researchers are studying whether certain genes from extremophiles like D. radiodurans can be safely adapted and integrated into human cells. Preliminary work in model organisms shows clear improvements in DNA repair speed and accuracy, suggesting that enhanced resistance may one day be feasible.

Borrowing Protective Proteins from Tardigrades

Tardigrades—tiny animals known for surviving in space—produce a unique protein called Dsup (short for “damage suppressor”). Dsup surrounds DNA like a physical shield, reducing radiation-induced breaks by up to 40 percent.

Human cell cultures engineered with the Dsup gene have shown statistically significant increases in radiation tolerance. If such modifications could be applied safely and reversibly to astronauts, the protection would be substantial, especially during solar storms.

On-Demand Genetic Defense Switches

Another research direction involves genetic “switches” that activate protective mechanisms only when radiation levels spike. These systems could raise antioxidant production, increase DNA stabilization proteins, or temporarily slow cell division to reduce mutation risk—all triggered automatically by environmental sensors inside the body.

A Combined Solution for Deep-Space Survival

Most scientists agree that no single strategy can fully protect the human body from cosmic radiation. Instead, future astronauts may rely on a multilayered approach that includes:

- lightweight spacecraft shielding

- melanin-rich or nanoparticle-enhanced tissue implants

- genetic modifications that reduce cellular damage

- pharmacological boosters for acute radiation events

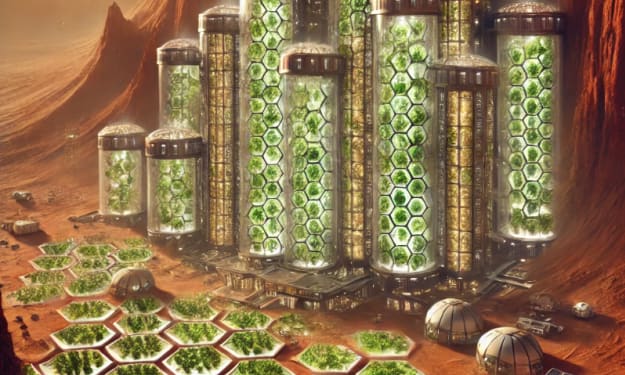

Together, these technologies could reduce radiation exposure to levels compatible with multi-year missions, opening the door to permanent settlements on Mars, rotating crews on lunar bases, and eventual travel beyond the asteroid belt.

Challenges Ahead

Despite promising results, these solutions come with significant scientific and ethical considerations. Long-term biocompatibility must be proven for implants, while genetic modifications require rigorous oversight and societal consensus. Yet the direction is clear: the future of human spaceflight depends not only on engineering better spacecraft, but also on engineering the human body itself.

As research accelerates, astronauts of the future may not simply travel through space—they may be biologically adapted for it.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.