How the first black holes in the universe evolved so quickly

The clock's black holes

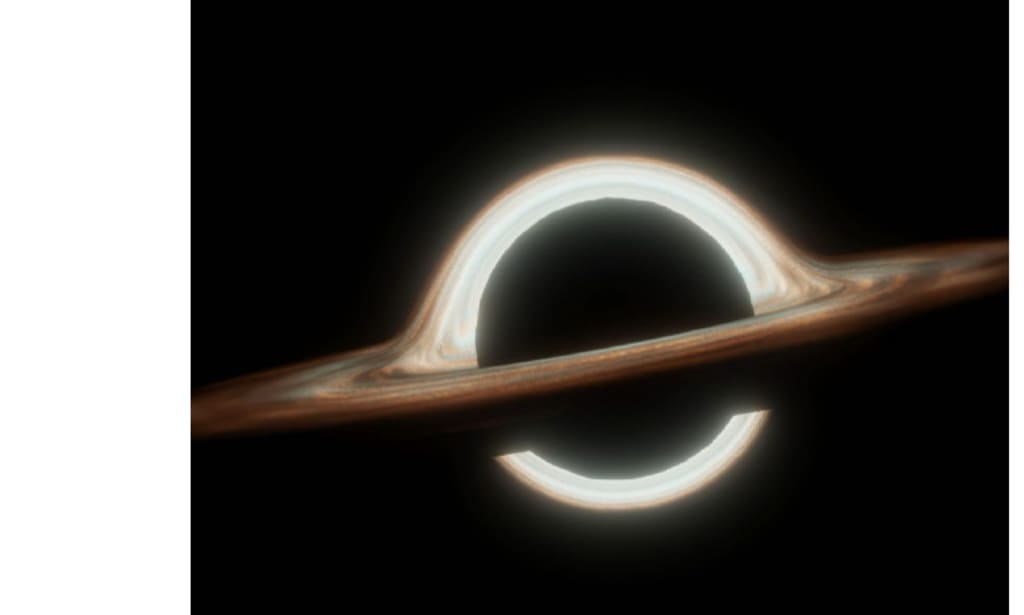

Astronomers have long been perplexed by how small black holes in the early cosmos grew to tens of thousands of times the mass of the Sun in a matter of million years.

Their speedy increase puts pressure on conventional growth models, which find it difficult to close such a huge gap so rapidly, but it also helps explain why big black holes already occur in the early chapters of the universe.

According to new models, those early black holes may have grown more quickly than previously believed due to tiny windows of time when gas was delivered by young, chaotic galaxies.

Long-standing conflicts between measurements and hypotheses of the formation of the universe's first giants may be resolved by this rapid development.

The clock's black holes

Daxal Mehta, a Ph.D. candidate at Maynooth University (MU), presented the outcome. His research demonstrates how these early settings made growth possible that was previously thought to be unattainable for such modest beginnings.

Gas was crammed into small centres by gravity in the early galaxies, and rather than settling peacefully, the gas continued to collide. A black hole could gather mass more quickly than its neighbours thanks to accretion, which is the slow inward fall of gas caused by gravity.

Additionally, angular momentum was removed by turbulence and stream collisions, allowing material to continue spiralling downward instead of safely orbiting at a distance. Even though some seeds discovered short, rich feeding zones, the majority of seeds remained tiny since such conditions were likely limited to certain areas.

Where seeds of black holes grow

The point at which the force of outward radiation equals the force of gravity is known by astronomers as the Eddington limit.

When some of the earliest metal-free stars, such as Population III stars, collapsed directly into black holes, light seeds most certainly formed. Compared to other formation pathways, the fall of those stars may have left behind lighter black hole seeds because they were made entirely of hydrogen and helium.

Mehta stated, "It was previously believed that these tiny black holes were too small to grow into the massive black holes observed at the centre of early galaxies."

As infalling gas heats up, black holes emit light, which can exert pressure on the same gas that drives expansion. However, trapped light escaped less effectively in dense, swirling flows, so gas continued to plunge within as the black hole blazed.

Super-Eddington accretion is the term for this type of excessive growth, a brief period in which feeding proceeds more quickly than previously permitted.

Gas simulation at small sizes

Simulations that tracked gas on scales much smaller than a normal star cluster inside a galaxy were necessary to capture these bursts. To stop dense gas clusters from blending together, the scientists tightened the grid until each cell only covered a few trillion miles.

Short feeding spikes were made possible by this resolution, which allowed gravity to draw gas into tiny streams and discs surrounding the seed. Because just a few hundred million years of cosmic time could be tracked by the highest-detail runs, MU computers had to pay a price.

The universe is reshaped by feedback

Due to the ability of both nascent stars and black holes to burn and release gas, young galaxies did more than simply feed black holes. The energy and momentum returned to nearby gas is known as feedback, and it can stop development by removing fuel.

Bursts in MU runs frequently terminated after heating or explosions increased pressure, making it more difficult to collect the surrounding material. Nevertheless, a small percentage of seeds broke through before the gas evaporated, demonstrating that unusual beginnings were not necessary for the process.

Spurts of black hole growth

While some of the seeds in the simulations flourished in brief spurts lasting only a few million years, the majority remained silent. For a moment, they were encircled by clumps of cold gas, and gravity forced the flow inward until heating or explosions forced it out.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) may be able to capture photos of that phase because each burst could make a seed brilliant.

Mehta stated, "What we have demonstrated here is that these early black holes, despite their small size, are capable of growing spectacularly fast, given the right conditions."

Novel perspectives on the expansion of the universe

Black holes that seem much too enormous for the brief time available after the Big Bang have already been discovered by JWST. Researchers connected a quasar to an X-ray source at a redshift close to 10, a distance indicator based on how much light has stretched over time.

Although Mehta's simulations showed that light seeds could occasionally catch up quickly, that item keeps heavy-seed ideas alive. Because each development history leaves distinct gas and stellar traces, improved observations of host galaxies will determine which path is dominant.

A fresh test is provided by gravitational waves.

The Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), a projected space observatory with detectors intended to track gravitational waves—ripples in spacetime from moving masses that pass through dust with little loss—is scheduled to launch in 2035.

Larger black hole seeds combine more loudly, therefore LISA may record more low-frequency events if many light black hole seeds formed quickly in the early universe.

A quiescent black hole leaves no discernible electromagnetic signature until it resumes feeding, so interpreting those signals will still require careful modelling.

When combined, these findings provide a connection between the chaotic environment within infant galaxies, the formation of the earliest stars, and the black holes that subsequently anchor galactic centres.

They also serve as a reminder that important physics might be overlooked by simulations, so future LISA detections and telescope observations are essential to figuring out how widespread this fast-growth pathway actually was.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.