Atomic Atomic Saturation

Feeling the Limits of Atoms: A Deep Dive into Atomic Saturation

Atomic Atomic Saturation

I have always been fascinated by the moments in science when nature seems to quietly whisper: “This is as far as I will go.” One of these whispers emerges in the world of atomic physics, in a phenomenon known as atomic saturation. It is an elegant yet stubborn limit in the interaction between light and matter, a point beyond which the rules we expect no longer apply in a simple way.

In its essence, atomic saturation describes the point at which an atom’s absorption of light stops increasing, no matter how much we increase the light’s intensity. At low intensities, atoms absorb photons in a predictable, linear fashion. But as we keep increasing the intensity, we eventually reach a limit — the rate of absorption levels off, and the atom enters a “saturated” state. At this point, the probability of finding an electron in the excited state becomes comparable to finding it in the ground state. The system reaches a kind of dynamic balance, where further photons simply pass through without being absorbed.

The Physics Behind Saturation

Atoms consist of electrons orbiting around a nucleus, and each electron can occupy discrete energy levels. When a photon of the right energy hits an atom, it can excite an electron to a higher energy state. In a simple two-level atom model, the atom can be either in the ground state or the excited state. At low light intensities, most atoms are in the ground state, ready to absorb photons. But as the light intensity increases, more and more atoms are promoted to the excited state. Eventually, the population of the excited state approaches that of the ground state, and the absorption rate stops increasing.

This is the physical meaning of the saturation intensity — the specific light intensity at which the absorption rate drops to half of its low-intensity value. Beyond this point, the atoms cannot keep up with the incoming photons. The system is “bleached,” and the medium becomes more transparent.

Historical Milestones

The concept of saturation was first studied in detail in the mid-20th century. In the 1950s, researchers investigating nuclear magnetic resonance noticed that applying stronger and stronger radiofrequency fields did not indefinitely increase the signal. Instead, the system reached a limit. In 1955, Alfred G. Redfield refined the theoretical understanding of this behavior, laying the foundation for modern relaxation theory in saturated systems. His work helped scientists understand how populations in different energy levels exchange and reach equilibrium.

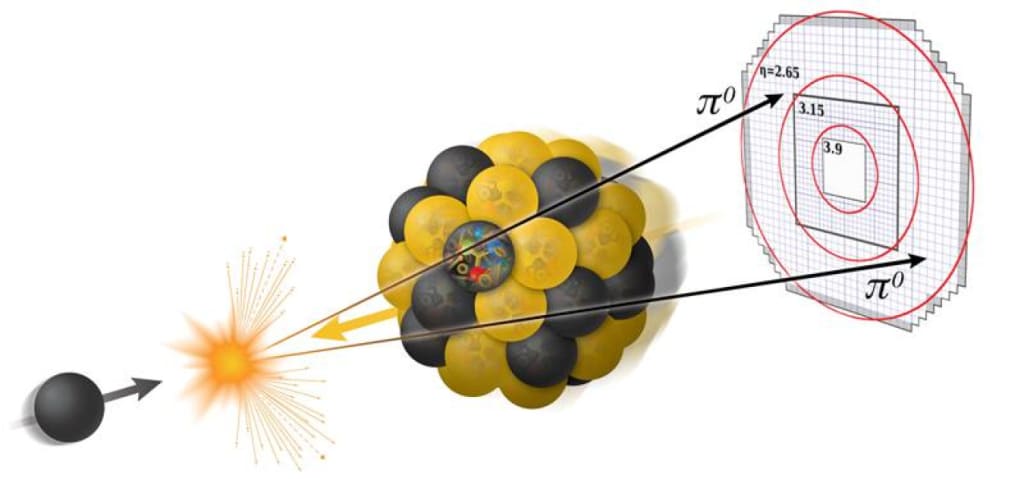

The arrival of lasers in the 1960s transformed the study of atomic saturation. Lasers provided intense, monochromatic, and coherent light sources — perfect for driving atoms to their limits. Scientists began to exploit saturation to improve spectroscopic resolution. One of the most important techniques born from this era was saturated absorption spectroscopy, which allowed researchers to measure atomic transition frequencies with incredible precision by overcoming the Doppler broadening that blurred spectral lines.

By using two counter-propagating laser beams, the technique could “lock in” on atoms with zero velocity along the beam direction, revealing the true, sharp resonance frequency of the transition. This breakthrough became essential in building the next generation of atomic clocks and frequency standards.

Famous Atoms and Experiments

Certain atoms became the “stars” of saturation experiments. Cesium, rubidium, and hydrogen have been studied extensively because of their simple energy structures and importance in timekeeping. In rubidium, for instance, saturation spectroscopy revealed hyperfine structures that became the basis for rubidium atomic clocks, now used in navigation systems and telecommunications.

Hydrogen, the simplest atom, offered a playground for testing fundamental physics. In the 1970s, saturation techniques allowed ultra-precise measurements of the hydrogen 1S–2S transition, providing one of the most accurate tests of quantum electrodynamics.

Cesium, with its well-defined hyperfine transition, became the official timekeeper of the world. The International System of Units defines the second based on the frequency of the cesium hyperfine transition — and saturation methods are a key part of measuring it so precisely.

Modern Applications

Today, atomic saturation is more than a curiosity of physics — it’s a tool that underpins many technologies. Atomic clocks, GPS systems, laser frequency stabilization, quantum computing experiments, and even some types of medical imaging depend on understanding and controlling saturation effects.

In quantum optics laboratories, researchers use saturation to probe the coherence properties of atoms and molecules. In cold atom experiments, scientists slow atoms down to near absolute zero and then study how they interact with light at intensities far below and far above the saturation point. This reveals details about atomic structure and light–matter interaction that cannot be seen in ordinary conditions.

A Personal Reflection

What captivates me most about atomic saturation is not just the physics, but the philosophy it hints at. In everyday life, we are used to the idea that more input gives more output — more effort yields more results. Saturation challenges that belief. It tells us there are limits built into the very fabric of the universe, boundaries we cannot cross simply by pushing harder.

When I imagine an atom reaching its saturation point, I think of a human mind or body reaching its own limits — a reminder that in both nature and life, balance often matters more than excess. The elegance of this natural boundary is a lesson in humility: the atom knows when to stop, even if we do not.

Feeling the Limits of Atoms: A Deep Dive into Atomic Saturation

I have always been fascinated by the moments in science when nature seems to quietly whisper: “This is as far as I will go.” One of these whispers emerges in the world of atomic physics, in a phenomenon known as atomic saturation. It is an elegant yet stubborn limit in the interaction between light and matter, a point beyond which the rules we expect no longer apply in a simple way.

In its essence, atomic saturation describes the point at which an atom’s absorption of light stops increasing, no matter how much we increase the light’s intensity. At low intensities, atoms absorb photons in a predictable, linear fashion. But as we keep increasing the intensity, we eventually reach a limit — the rate of absorption levels off, and the atom enters a “saturated” state. At this point, the probability of finding an electron in the excited state becomes comparable to finding it in the ground state. The system reaches a kind of dynamic balance, where further photons simply pass through without being absorbed.

The Physics Behind Saturation

Atoms consist of electrons orbiting around a nucleus, and each electron can occupy discrete energy levels. When a photon of the right energy hits an atom, it can excite an electron to a higher energy state. In a simple two-level atom model, the atom can be either in the ground state or the excited state. At low light intensities, most atoms are in the ground state, ready to absorb photons. But as the light intensity increases, more and more atoms are promoted to the excited state. Eventually, the population of the excited state approaches that of the ground state, and the absorption rate stops increasing.

This is the physical meaning of the saturation intensity — the specific light intensity at which the absorption rate drops to half of its low-intensity value. Beyond this point, the atoms cannot keep up with the incoming photons. The system is “bleached,” and the medium becomes more transparent.

Historical Milestones

The concept of saturation was first studied in detail in the mid-20th century. In the 1950s, researchers investigating nuclear magnetic resonance noticed that applying stronger and stronger radiofrequency fields did not indefinitely increase the signal. Instead, the system reached a limit. In 1955, Alfred G. Redfield refined the theoretical understanding of this behavior, laying the foundation for modern relaxation theory in saturated systems. His work helped scientists understand how populations in different energy levels exchange and reach equilibrium.

The arrival of lasers in the 1960s transformed the study of atomic saturation. Lasers provided intense, monochromatic, and coherent light sources — perfect for driving atoms to their limits. Scientists began to exploit saturation to improve spectroscopic resolution. One of the most important techniques born from this era was saturated absorption spectroscopy, which allowed researchers to measure atomic transition frequencies with incredible precision by overcoming the Doppler broadening that blurred spectral lines.

By using two counter-propagating laser beams, the technique could “lock in” on atoms with zero velocity along the beam direction, revealing the true, sharp resonance frequency of the transition. This breakthrough became essential in building the next generation of atomic clocks and frequency standards.

Famous Atoms and Experiments

Certain atoms became the “stars” of saturation experiments. Cesium, rubidium, and hydrogen have been studied extensively because of their simple energy structures and importance in timekeeping. In rubidium, for instance, saturation spectroscopy revealed hyperfine structures that became the basis for rubidium atomic clocks, now used in navigation systems and telecommunications.

Hydrogen, the simplest atom, offered a playground for testing fundamental physics. In the 1970s, saturation techniques allowed ultra-precise measurements of the hydrogen 1S–2S transition, providing one of the most accurate tests of quantum electrodynamics.

Cesium, with its well-defined hyperfine transition, became the official timekeeper of the world. The International System of Units defines the second based on the frequency of the cesium hyperfine transition — and saturation methods are a key part of measuring it so precisely.

Modern Applications

Today, atomic saturation is more than a curiosity of physics — it’s a tool that underpins many technologies. Atomic clocks, GPS systems, laser frequency stabilization, quantum computing experiments, and even some types of medical imaging depend on understanding and controlling saturation effects.

In quantum optics laboratories, researchers use saturation to probe the coherence properties of atoms and molecules. In cold atom experiments, scientists slow atoms down to near absolute zero and then study how they interact with light at intensities far below and far above the saturation point. This reveals details about atomic structure and light–matter interaction that cannot be seen in ordinary conditions.

A Personal Reflection

What captivates me most about atomic saturation is not just the physics, but the philosophy it hints at. In everyday life, we are used to the idea that more input gives more output — more effort yields more results. Saturation challenges that belief. It tells us there are limits built into the very fabric of the universe, boundaries we cannot cross simply by pushing harder.

When I imagine an atom reaching its saturation point, I think of a human mind or body reaching its own limits — a reminder that in both nature and life, balance often matters more than excess. The elegance of this natural boundary is a lesson in humility: the atom knows when to stop, even if we do not.

About the Creator

Mohamed hgazy

Fiction and science writer focused on physics and astronomy. Exploring the human experience through imagination, curiosity, and the language of the cosmos.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.