A Planet Where a Year Lasts 10 Hours: Life on the Universe’s Fastest Worlds

Space

When we think of a year, we imagine a familiar cycle: spring blossoms, summer heat, autumn leaves, and winter snow. It’s a slow, predictable rhythm days turning into weeks, months into seasons. But elsewhere in the universe, time moves at a different speed entirely. Imagine a planet where a full orbit around its star a year lasts just 10 hours. That’s right, half a day from one New Year to the next. Welcome to the realm of ultra-short-period planets, where time and temperature both go to extremes.

Cosmic Speed Demons: The Ultra-Short-Orbit Planets

Astronomers call them USP planets (ultra-short-period planets). These are exoplanets so close to their host stars that they complete a full orbit in less time than it takes you to get through a shift at work.

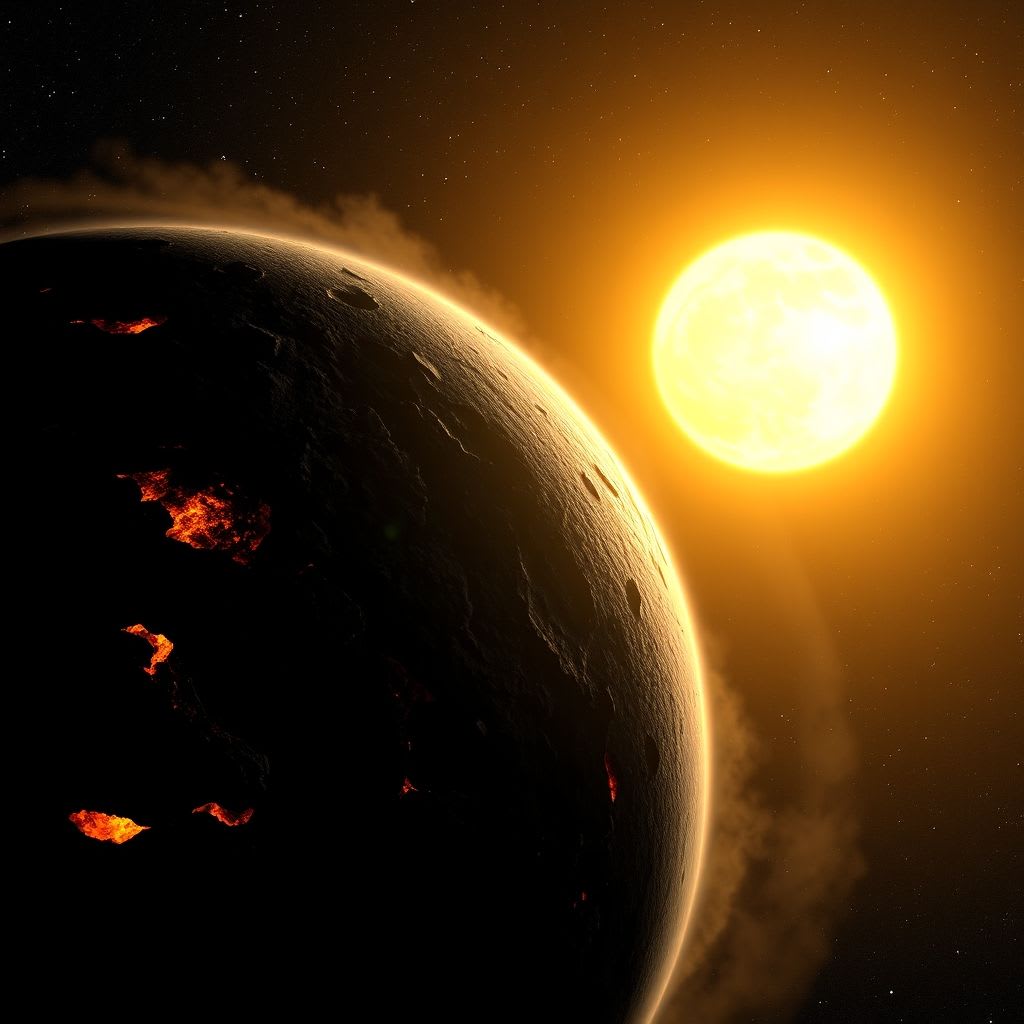

Take Kepler-78b, for example. This hellish world orbits its star every 8.5 hours, hugging it so closely that its rocky surface is constantly scorched. Or consider K2-141b, where the “year” lasts just 6.7 hours. On this planet, heat from the star is so intense that rocks vaporize into the atmosphere, rain back down as molten droplets, and cycle again in a never-ending storm of stone and fire. Scientists describe it as a “lava loop” between the planet’s blistering day side and its frozen night.

Could Anything Survive in Such a Place?

The short answer? Not likely—at least, not life as we know it.

Daytime temperatures on USP planets can exceed 3000°C (5400°F) hot enough to melt not just metal but solid rock. Any Earth-like lifeform wouldn’t stand a chance. The environment is brutally hostile: radiation from the star, intense gravity, and temperature extremes that would instantly destroy biological molecules.

But even if these worlds aren’t home to life, they’re treasure troves for scientists. Studying them offers clues about how solar systems form and evolve. Did these planets always exist so close to their stars? Probably not.

The Journey Inward: Death by Starfire

Many scientists believe that these planets started their lives farther out, perhaps as gas giants similar to Neptune or even Jupiter. Over time, gravitational forces and tidal drag pulled them inward, stripping away their thick atmospheres and leaving behind only a dense, rocky core.

What we’re seeing now are the naked remnants of former giants exposed planetary cores, like the stone hearts of fallen titans. These relics are living records of cosmic migration, reshaped by the unforgiving heat of their stars.

When Planets Pull Back: The Tidal Tug-of-War

Interestingly, these ultra-close planets don’t just suffer from their stars they also affect them.

Their strong gravitational pull creates tidal interactions that can slow a star’s rotation, distort its shape, and potentially change its magnetic behavior. Some planets even drag material from their own surface into space, forming comet-like tails made of vaporized rock and metal.

Yes, you read that right: a planet with a tail. It’s a mesmerizing image this stone world whizzing around its star, trailing a shimmering arc of dust and vapor in its wake.

Life in Fast-Forward: A Hypothetical Existence

Let’s take a moment to imagine what life would be like on such a planet.

A year is 10 hours. That means new seasons every few hours, a century in just a few Earth days. Your birthday would come before breakfast. You could finish school in a weekend.

Of course, with surface temperatures hotter than a welding torch, you wouldn’t survive long enough to celebrate anything. But if life existed perhaps in a sheltered region on the planet’s cooler night side it would have to be completely alien. Adapted to constant darkness, massive gravitational stresses, and possibly even dependent on energy from tidal heating rather than sunlight.

Why These Worlds Matter

Ultra-short-period planets may seem like cosmic curiosities, but they serve a vital purpose in astronomy. They show us that the universe plays by no single set of rules. What seems impossible on Earth is normal somewhere else.

They push the limits of what we consider a “planet,” what kinds of orbits are stable, and how stars and worlds interact over time. And as our telescopes like Kepler, TESS, and soon PLATO and JWST grow more powerful, we’re likely to discover even more of these extreme environments.

Final Thoughts

A planet with a 10-hour year is no science fiction it’s science fact. These cosmic speedsters are a reminder of how diverse, violent, and utterly fascinating our universe can be. They might not host life as we know it, but they could teach us how life begins, how worlds die, and what kinds of planetary systems might exist far beyond the boundaries of our own.

And who knows maybe, just maybe, hidden in the darkness of some ultra-short-orbit planet’s night side, something unimaginable is waiting.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.