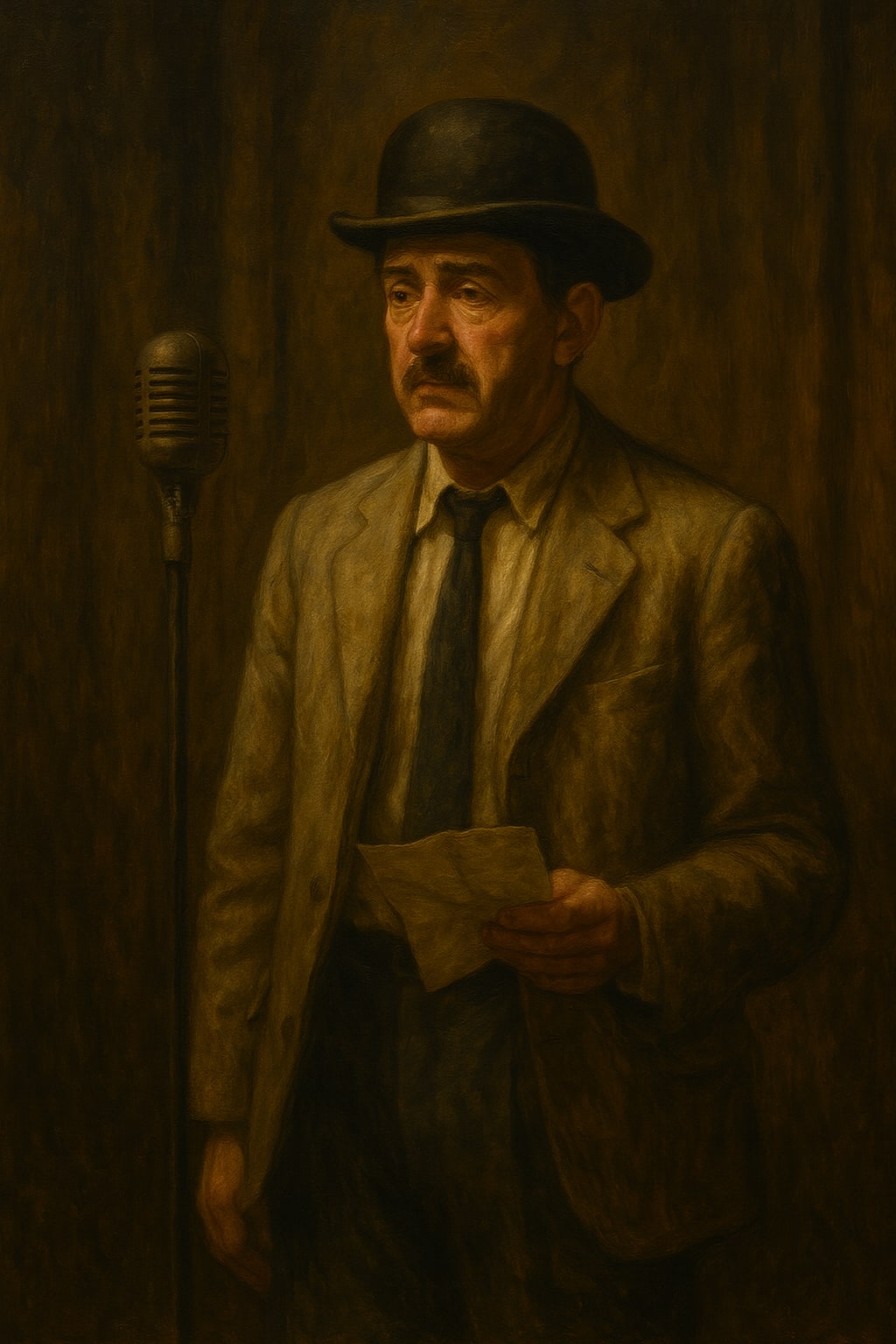

The train sighed into Weston-super-Mare with all the enthusiasm of a man told there’s a meeting after lunch. Tommy Blythe stepped down with his suitcase in one hand and his bowler in the other, nodded to the gulls as if they were ushers, and followed the smell of salt and fried batter toward the front.

The posters went first. They always did. The railings along the prom wore them like medals—bright faces grinning between rusted bolts, names you could hum to, dates that suggested the town wouldn’t dare let summer pass without applause. Tommy found his: third from the bottom, a misprint haggling with his dignity.

TOMMY BLYTH — *The Man With A Thousand Lines.*

“They’ve spelt it without the ‘e,’” he told his hat. “Drop the letter and you drop the man. That’s my career, right there. Missing vowels.”

He booked into the kind of hotel where the carpets spelled out history in cigarette burns and the landlady called everyone “love” the way a magistrate calls everyone “defendant.” His room had a view of the alley and shared a wall with a boiler that liked to rehearse after midnight. He set his bowler on the dresser, took a breath, and told his reflection, “Right. Work.”

The pier theatre still smelt of last year’s candyfloss and last century’s paint. Dust hung in the stage lights like an audience that hadn’t paid, and when Tommy walked to the centre mark the boards gave underfoot with a tired willingness he recognised from his knees.

“Mr Blythe,” said the stage manager, a young man whose clipboard had better posture than he did, “we’re just running cues. Tight turnaround tonight, full dress tomorrow, you open on Friday.”

“Of course,” Tommy said. “Leave the laughter till Friday; I’ll rehearse the silences.”

He warmed up for an audience of two: the stage manager and a carpenter mending something offstage with the kind of hammer that improves a man’s mood with every blow. Tommy’s patter came out clean but slow; the beats arrived like late trains. He skipped the bit with the newspaper, fumbled the transition to the page-boy routine, then found his grip again with the story of the landlady who watered her gin plants. The carpenter laughed once—against orders, by the look he got for it.

A man with the hair and expression of a velvet lampshade wandered in from the wings and watched for a minute with professional confusion.

“That monologue you do,” he said when Tommy finished, “about music halls. Is that… necessary?”

“It’s the spine,” Tommy said.

The man tilted his head like a spaniel hearing jazz. “Thing is, nobody gets that old stuff now. We need faster, brighter, you know? We’ve got a yodeller closing the first half. She’s terrific. Hits notes you can’t even see.”

“Notes are cheap,” Tommy said, dusting his sleeve. “Meaning’s the expensive bit.”

“Right,” said the lampshade, which turned out to be the headliner’s manager. “Just keep it tight, yeah?”

After he left, the stage manager approached with diplomatic eyebrows. “They like speed now, Mr Blythe. The audience. Tik-tok.”

“That’s a clock, is it?” Tommy said. He took out his pocket square and polished the bowler as if the hat had to look brave on behalf of the man beneath it. “Tell the clock to mind how it talks to me.”

There are things a man doesn’t put into the room with other people, even when those people are scenery and nails. Tommy kept his hands on the rituals: hat, cuff, breath. They were little doors back to a night when the air gasped with laughter and the orchestra leader winked at him over a trombone slide because they were both young enough to think the curtain would never come down.

Back at the hotel, he found yesterday’s paper in the lounge, unread except for the crossword and an opinion column about traffic that looked enraged at the concept of wheels. On page seven he saw the name that stiffened his spine: Rowland Fisk. *The Sunday Mirror’s* man with the pen like a scalpel. Visiting Weston to review the Pavilion revue, the write-up said, next week.

Tommy took the old calling card from his wallet and laid it against the newsprint, smoothing both with his thumb until they matched their age. He remembered the train—how the bowler had flown and the guard had shouted and Fisk had smiled with something like sympathy. *Keep the roof on, Blythe.*

That night, he walked the promenade in the kind of wind that apologises for being British and cold. The booth stood closed against the railings: Punch and Judy, painted sunshine gone chalky with the years. He tipped his hat at it. “Show’s over, pal,” he said. “We’ll guard the sand till the children come back.”

The booth stared through him, exactly as critics did.

Friday came like a booking you’d forgotten you’d accepted. The orchestra tuned to the key of “nearly,” the chorus line practised smiles that could stop traffic at twenty yards but not at thirty, and backstage the air filled with hairspray, pessimism and the cocoa smell of stage makeup.

“Five,” called the stage manager, which meant ten. Tommy stood behind a flats wall that was pretending to be a drawing room, bowler tilted, hands steady. The yodeller went on before him; you could tell by the sudden rise in noise like an ambulance attempting operetta. She was good. He resented her for it, liked her for being good, resented himself for liking her. There’s no mature version of that equation.

“Three,” came the call, which meant eight. He watched from the wings and saw Rowland Fisk in the third row, as if a ghost had bought a ticket out of politeness. The critic’s mouth wore the small, almost gentle line of a man who had seen too many people try and saw fewer succeed than deserved to. He had the stillness of an expensive pen left uncapped.

“Places,” the stage manager said, which means start breathing now or never.

Tommy walked out into the light carrying forty years that felt like one very long step. The applause came the way you greet an uncle you haven’t seen in a while: kind, curious, cautious. He began with the quick stuff—a jab here, a turn there. The first laugh skidded past him like a stone on a flat sea: contact, then silence. He found his rhythm on the third gag, mislaid it on the fifth, and by the seventh he could hear someone unwrapping a sweet in Row G with the attention of a surgeon.

He told the music-hall monologue anyway.

“Once upon a time,” he began, “you could buy a laugh for a farthing if you smiled as you handed over the coin. Now they want receipts, and the till gets audited.”

There was a chuckle in the cheap seats—bless them—and a cough from somewhere expensive. He saw Fisk’s head tilt. He could feel the tide turning the wrong way. The routine would run out, and he would bow and leave and the critic would perform that genteel violence his kind paid rent with.

He stopped. Not dramatically; the way a man stops at the top of the stairs because he is suddenly old enough to be careful. The silence made everyone in the theatre remember how their own breathing worked.

“Forgive me,” he said. “I was about to tell you a joke about a landlady with a gin plant. Very educational. But it isn’t the right one.”

He took off his bowler, held it, looked at it the way you look at a photograph of a person who is both alive and not presently available.

“Once,” he said, “I pulled the communication cord on a train because my hat decided to leave me. Not out of respect, I think; it just fancied an adventure.”

It wasn’t a routine. It wasn’t quite a confession. It was something threaded between, tight as a wire over water. He told them about the tunnel, and the guard’s lantern, and the absurdity of seeing a hat on a railway sleeper looking pious. He told them about Rowland Fisk in a corridor, and a compliment that had stuck like a note you don’t deserve but pretend you can sing. He mentioned the Bishop of Bath and Wells and the kind of language guards explode into when gravity gets ideas. He didn’t hurry. He let the audience walk with him one pace behind.

“They say a man shouldn’t look back,” he said. “But if I hadn’t, I’d still be chasing this thing through the dark. There’s dignity in pursuit, you know, even if the quarry’s a roof for an ageing bungalow.”

The laugh that came then had weight to it, like a good coat. It wrapped around him without fuss. He found his timing like a pen you thought you’d lost but had only been sitting under your own hand all along. He moved into the old lines—not the ones the lampshade wanted, the ones with corners—and they landed because he wasn’t pleading with them. When he reached the bit about the landlady and the gin plant, he almost didn’t say it. Then he did, and the house laughed as if it had been waiting there all evening for proper permission.

He closed with a small bow—no flourish. The applause wasn’t wild, just real. In the third row, Rowland Fisk stood. He didn’t clap beyond his station; he didn’t do anything theatrical with his eyebrows. He stood, nodded, and sat. It was enough.

Backstage, the stage manager put a hand on Tommy’s arm and squeezed with the solemnity of a man who had just learned the difference between fast and right. The headliner’s manager avoided him with the fear of someone who senses an opinion forming and doesn’t want to be near when it develops.

At the pier café, which believed in tea the way ministers believe in rumoured miracles, Tommy took a corner table and arranged his hat, paper, and saucer as if they were going on after him. The night breathed outside; the neon Open sign buzzed like a bluebottle with ambitions.

The early edition arrived under the arm of a lad whose idea of literature was football fixtures. He sold Tommy a copy and asked for a signature, then looked bewildered when it was given with genuine gratitude.

The review sat on page five, which is not exile but not the throne. The headline was smaller than his pride but larger than his fear.

**THE OLD COMIC WHO REMEMBERED HIS LINES — AND WHY THEY STILL MATTER**

by Rowland Fisk

Tommy read. Fisk wrote like a man placing a hand on your chest to stop you stepping into traffic. He spoke about time and tide, about jokes as furniture with dents you’ve grown to love. He said the act began old and turned human; that the hat routine—was it a routine?—made a different kind of sense than laughter usually allows. He was honest about the early falter. He was kind about the recovery. He used the word “grace,” once, in a sentence that did not sound like a eulogy.

Tommy folded the paper carefully and tucked it into the bowler as if good words needed a roof in this climate. He finished his tea, which had cooled into that particular brown associated with church basements, put a coin under the saucer for decency’s sake, and walked out into a town first finding the edges of morning.

The tide had turned, as promised by men with charts and women with sense. Deckchairs lay like dominoes, and the gulls had woken up enough to complain about it. He walked down onto the sand—firm, damp, honest—and went to where the foam pretended to be lace. He took off his shoes, then thought better of it and left them on. There are gestures better made by actors with health insurance.

He dipped the bowler in the sea. It gulped, shivered, came up with a new shine that was part brine, part idea. He shook it gently, because a man should not traumatise his own hat in public, and settled it on his head.

A boy along the railings pointed and said something to his mother that might have been “Is that man going swimming in his suit?” The mother said something back that sounded like “Don’t stare,” which is the English for “I’m staring too.”

Tommy looked along the beach and saw the Punch and Judy booth again, its painted grin as heartbreakingly brave as ever. He saluted with two fingers touching the brim, military-style, and the booth, being a wooden thing, coped in silence.

He walked to the steps and sat to let the water lace his shoe-tips. The newspaper in his hat made a comfortable weight, like money used to. He thought about the lad with the fixtures, about the yodeller and her clean, furious notes; about the manager who liked speed and the stage manager who had learned something. He thought about how many of the people who had laughed that night would remember him in a week, and then he thought—gently, without bitterness—that it didn’t matter whether they did.

He thought about Rowland Fisk, who had stood without fanfare in the third row to mark a moment. He wondered whether the man had enjoyed himself or merely recognised workmanship. Then he let the wondering go. A compliment, like a laugh, belongs to the person who gives it; the recipient’s job is to put it somewhere it won’t get spoilt.

Behind him, the town began its morning theatre. Carts clattered. A woman told a dog to be reasonable. Somewhere a radio insisted that the weather would be “bright spells with occasional showers,” which is how a doctor might summarise a life if he were in a hurry.

Tommy stood, which he would be doing for as long as his legs allowed, and brushed a line of sand from his trouser knee. The sea clapped once against the wall, then again, polite and not entirely displeased to see him.

“The sea didn’t part,” he told the gulls, the booth, the town, and perhaps himself. “But it clapped politely. That’ll do.”

He went up the steps with the care of a man carrying something fragile—himself, the hat, the folded newspaper that made a sound like new paper makes when you move it: the sound of tomorrow thinking about becoming today. He turned along the promenade toward the theatre, because there was another show tonight and pride, for all its sins, knew how to clock in on time.

On the way he passed the posters again. His name, missing its “e,” looked less like an error and more like a stage-name you might choose if you were feeling aerodynamic. He considered, just for mischief, asking the stage manager to take a pen and add the letter. Then he decided he liked the absence.

Let it be a gap, he thought. Let the audience put it back in themselves.

Outside the stage door he paused, set the hat square, and rehearsed the line he would say to the stage crew when he walked in: something light, something that sounded like a man who had always known the floorboards would hold him. It came without effort.

“Morning,” he said to the doorman, whose newspaper carried a headline Tommy had already memorised. “We’re open, are we? Good. Let’s not waste any of our silences today.”

The doorman lifted a palm in lazy salute. “Good show last night, Mr Blythe.”

“That’s what the sea reckons,” Tommy said.

Inside, the wings were still half-dark and the stage looked like a church before the parish arrives. He put the hat down on a chair, took the newspaper from it, and slid the review into the inside pocket of his jacket. Not close to the heart—he didn’t trust that sort of symbolism—but near enough to feel if it ever started to slip.

He went to centre-stage, found the little cross someone had chalked there for the chorus line, and stood on it with the confidence of a man who has discovered the secret: that the trick of continuing is not to win back the world, but to keep oneself—and a hat, and whatever else has earned the right—whenever the wind gets up.

“Places,” he told the empty theatre. It said nothing, which is how theatres say yes.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.