There was a card of thick cream dropped through the boarding-house letterbox that afternoon, and Mrs Collier downstairs called up the stairs as if she were hailing the Queen Mary. “Mr Blythe! Something official! Don’t tread on the runner; I’ve just polished it.”

Tommy took the envelope in both hands, as though hot. The script had that municipal curl to it, the kind of handwriting that had been taught by rulers and carried a faint smell of polish and reprimand. He slit the flap with a thumbnail and read.

The Mayor and Entertainment Committee of Weston-super-Mare request the pleasure—his pleasure!—of his company at the Civic Banquet, to be held in the Town Hall on Thursday evening, “in recognition of your contribution to the cultural life of Weston-super-Mare.”

He read it twice and then a third time, turning the card to see if there was a catch printed in small type on the back. There was only an impression where the crest had been stamped so hard it had bruised the paper.

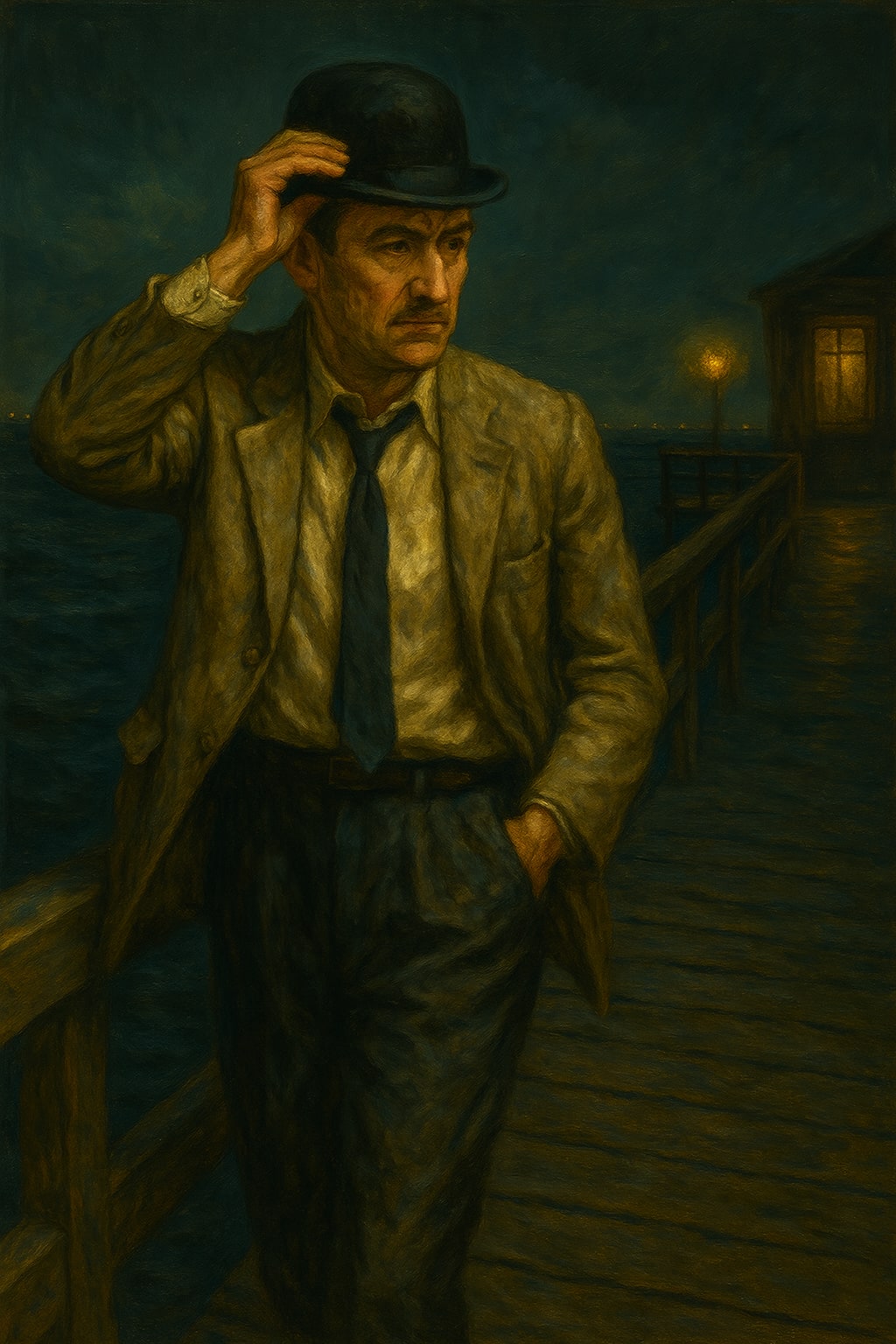

“Recognition,” he told the mirror. His reflection looked hopeful by habit, doubtful by experience. He set the bowler squarely on his head; it had assumed an air of command since its incident with the tunnel. He brushed his suit and shook the cuffs as though they were reluctant dogs. He practised a smile that contained gratitude without gratitude’s loss of dignity.

“Don’t be late,” Mrs Collier said, the phrase she used for all male failings, handing him his coat as if handing over a verdict.

The Town Hall had been buffed to within an inch of its bricks. Flags stood at soldierly attention; portraits of previous mayors in generous oil surveyed the foyer with the sadness of men who missed their chains of office and their breakfasts. A woman with a municipal orchid hovering on her shoulder like an inspector clipped the corner of Tommy’s card and said, “Through there, entertainers’ table at the back, dear.”

The hall glowed with sherry and brass. The Mayor’s dais was a small stage with a long white table, as if supper were about to perform. Dignitaries sat in a row, the men with their chests arranged, the women wearing hats big enough to shelter an orchestra. The entertainers’ table, marked with a card, was tucked near the fire exit as if talent were a fire hazard.

Tommy found two familiars already seated. Sid Mason, whose act had once involved a trombone and an uncooperative ladder, now leaned on a walking stick as if it might yet play a tune. On his other side, Dolly Winch, a singer from the old days whose voice had smoked itself into velvet, lifted her glass with a grin.

“Tommy Blythe,” Sid said, “the human interval.”

“Dolly,” Tommy said, kissing the air somewhere decorously near her cheek. “Still tuning the seagulls?”

“They sing sharper than me now, love. Cheaper, too.”

A woman with a badge that said Entertainment Subcommittee—Chair bobbed at their elbows. “Wonderful to have you,” she said in the careful voice of one handling historic crockery. “You’re still doing that… stand-up thing?”

“I sit down more often,” Tommy said. “It saves on lightning.”

She scribbled this as if it might be useful at a future meeting and bobbed away.

The meal arrived in ranks, gravy mustering at the low places. Pudding was announced by a drumbeat of cutlery. Conversations rose and sank like polite surf. From the dais, the Mayor shook himself free of napkin and stood. He was a round man with a chain and the expression of one who had rehearsed. Applause shuffled into being.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” the Mayor said, with the assurance of a man who had the microphone and the year. “Tonight we celebrate those who bring colour and joy to our lovely town. The fishermen, the small shopkeepers, our fine performers—yes!—and all who make Weston-super-Mare the jewel of the Bristol Channel.”

Tommy watched the word “jewel” leave the Mayor and ascend with the hope of finding a suitable setting. It hung for a moment in the chandelier and went out.

“And let us have a round for our very own Mr—” he consulted a card, “Mr Blye—Blythe!—who has entertained visitors at the end of our pier for— goodness—many seasons.” The Mayor smiled as if he’d invented arithmetic. “Punch and Judy is a noble tradition, and long may Mr Blythe’s puppets—”

Polite laughter washed the hall. Tommy smiled in the way one smiles when introduced as one’s cousin. He felt the bowler on his head grow heavier by an ounce.

Sid leaned in. “At least he didn’t call you The Human Cannon.”

“Wait till dessert,” Tommy said. “He’ll fire me through the trifle.”

Waiters poured champagne with the care of chemists. Dolly raised her glass. “To not being dead yet.”

“To being printed in the programme,” Tommy said, and they clicked.

A man with a thin moustache and a clipboard materialised. “Mr Blythe,” he whispered, polite as a pickpocket, “the Mayor was wondering if you might—ah—offer a few words. Or even a quick turn. Nothing elaborate. Before the syllabub.”

Tommy looked past him to the dais. The Mayor was laughing at something his wife had said while stacking petit fours like medals. The councillors examined their nails with civic attentiveness. The orchid woman was nodding in approval at nothing.

“Of course,” Tommy said. The hat remained on his head; it was not the sort of hat that let you refuse.

He walked to the podium with that slow, deliberate gait comics preserved for when they were not sure of the floor. The microphone squealed, apologised, and settled. Faces turned toward him in a wave. The chandeliers glittered. Sid lifted a thumb. Dolly blew an invisible trumpet.

“Good evening,” Tommy said. The room murmured an evening back. “I’m Tommy Blythe. Not Punch. Not Judy. Just the chap who stands between them and the sea and hopes neither takes offence.”

A patter of laughter, kind, encouraging.

“I had an invitation,” he said, holding the card between finger and air, “which arrived through the letterbox like a summons from the Almighty. Recognising my contribution to the cultural life of the town. I had to check they hadn’t mistaken me for the man who paints the shelter on the promenade.”

More laughter. The hat settled by a hair’s breadth. He found the rhythm that used to come like second breath.

“I’ve performed at the end of more piers than I’ve had hot teas. Some of them sturdy as battleships, some of them held together by sentiment and salt. The thing about a pier is it’s a road to nowhere, which is very British— we like the idea of going out to sea without the trouble of leaving.”

The room warmed. Even the portraits seemed to lean forward.

“And we comics,” he said, “we do our bit. We tell jokes at the end of the road to nowhere. We make a noise like happiness. We collect laughter in a tin and cash it at the box office. It’s honest work, mostly. Hard on the feet. Harder on the pride.”

He heard the last word drop. It made a small tidy sound on the parquet.

“Because pride’s dearer than fish,” he said, and saw Dolly’s grin soften. “It’s what keeps a hat on a man’s head when the wind’s from the channel. It’s what keeps him from doing a dance for a free pudding. It’s what keeps him going when his name’s so far down the bill it’s holding up the staples.”

The laughter thinned, not because they objected but because there is a point at which laughter knows it is trespassing.

“So here’s to you,” he said, and turned toward the hall as though addressing an old friend with whom he had quarrelled. “Here’s to Weston-super-Mare, whose piers keep their feet in the water and their heads in the rain. Here’s to the families who let the sand into their sandwiches and still smile. Here’s to the fisherman and the small shopkeeper and the council clerk who knows the difference between a line in a budget and a line in a song. And here’s to the end-of-the-bill comics who stand in the draught and try to make the draught laugh.”

He paused. The silence that followed was not empty; it was attentive, the sort that likes you but is not sure whether to admit it in public.

“So,” he said, lighter, “eat your syllabub. I’ll keep the sea from coming in while you do.”

Applause began in two places at once and found company; not a storm but a weather system. Dolly clapped as though she were seeing off a ship. Sid’s stick did percussion. The Mayor, to his credit, rose and nodded with a face that suggested he had understood the general gist.

Back at the fire exit table, the orchid woman fluttered. “Lovely,” she said. “So… human.”

“On a good night,” Tommy said, sitting. His hands trembled, and he hid them under the cloth where bread rolls go to die.

People drifted toward the cloakroom with the amiable urgency of those for whom taxis have been summoned. The Master of Ceremonies shook Tommy’s hand twice, which is the official quantity for an apology unadmitted. Dolly squeezed his arm.

“You told them,” she said.

“I told them the kind bits,” he said.

Outside, the rain had finished the work and gone home. The town lay rinsed and shining, the lamplight puddled and the gulls auditing the bins. Tommy stepped out under the great municipal doors and breathed the smell of salt, petrol, and something sweet—perhaps the restaurant on the corner boiling hope with sugar.

Cars flashed and were gone. The Town Hall settled itself back into stone. Tommy walked toward the pier. He passed a triple-breasted poster for the summer revue, the letters arranged in patriotic optimism. His own name, far below the acrobats and the singing twins, crouched like a cat at the edge of the step.

He removed his hat and held it level with the name. “We must stop meeting like this,” he said to the paper. “People will talk.”

On the railings beyond the promenade, the sea shifted and reflected streetlights in broken ribbons. He went down toward the boards. The pier sighed the way wood sighs when it remembers trees. Halfway down, a door at the side of the theatre threw a slice of light onto the boards and then closed, leaving the slice behind for a moment, like a promise reluctant to vanish.

He leaned on the rail. Somewhere out in the dark a bell rang on a buoy and then, thinking better of it, stopped. He felt in his pocket for a cigarette and found a peppermint, which he accepted as an omen. The wind combed his hair with a rough hand and then patted the hat back into place—the sea had manners when it wanted to.

“Thank you, Weston,” he said to the waves, pitching it just loud enough for them to hear. “You’ve been a lovely audience.”

He imagined the hall again—the chandeliers, the orchid, the faces that had nearly cared. He imagined the applause growing a little in the memory, as applause does if you’re kind to it. He imagined tomorrow’s rehearsal and the long walk down the boards with the tin under his arm.

“Keep the roof on,” a remembered voice said—Rowland Fisk, on the train, handing him a card like a benediction. Even a bungalow looks grand from the right distance.

Tommy tilted the brim to the invisible critic, to Dolly’s velvet laugh, to Sid’s stick. He watched the black water write its slow initials on the pilings. He allowed himself one small, treacherous thought, not larger than a match flame, that mischievously refused to blow out.

He straightened, knocked his knuckles gently against the rail twice—for luck, for rhythm—and turned back toward town, carrying the night like a final line that had landed.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.