The Old Bill

The Man Who Argued with His Own Poster

The stage had that smell particular to British theatres that had seen too many winters — a mixture of damp curtains, dust, and ambition. The lights buzzed half-heartedly above the pier, the kind of bulbs that gave up before the actors did.

Tommy Blythe stood centre stage, running a hand along the frayed velvet of the main drape. “Still got your figure, old girl,” he murmured, then added, “Shame about mine.”

A young stagehand was sweeping the boards, his broom tracing lazy arcs. He couldn’t have been more than nineteen, cheeks like unbaked bread, eyes too open for show business.

“Afternoon, Mr Blythe,” the lad said, without looking up. “You done for the day?”

Tommy tilted his bowler hat to the correct angle — the one that said ‘professional’ from the front and ‘tired’ from the back. “I’m never done, lad. I just take commercial breaks.”

The broom paused. “Were you famous once?”

Tommy smirked. “Only on Tuesdays. And only if the wind was right.”

The lad laughed, the way people laugh when they don’t quite get the joke but like the sound of it. Tommy looked out into the empty house — the rows of red seats gaping like a toothless grin. “They used to queue, you know. Down the pier, round the corner, past the fish shop. Whole town smelled of vinegar and expectation.”

He reached for his cigarette case, remembered the doctor’s warning, and decided instead to chew on nostalgia.

“Used to,” he repeated softly, as if testing the taste of it.

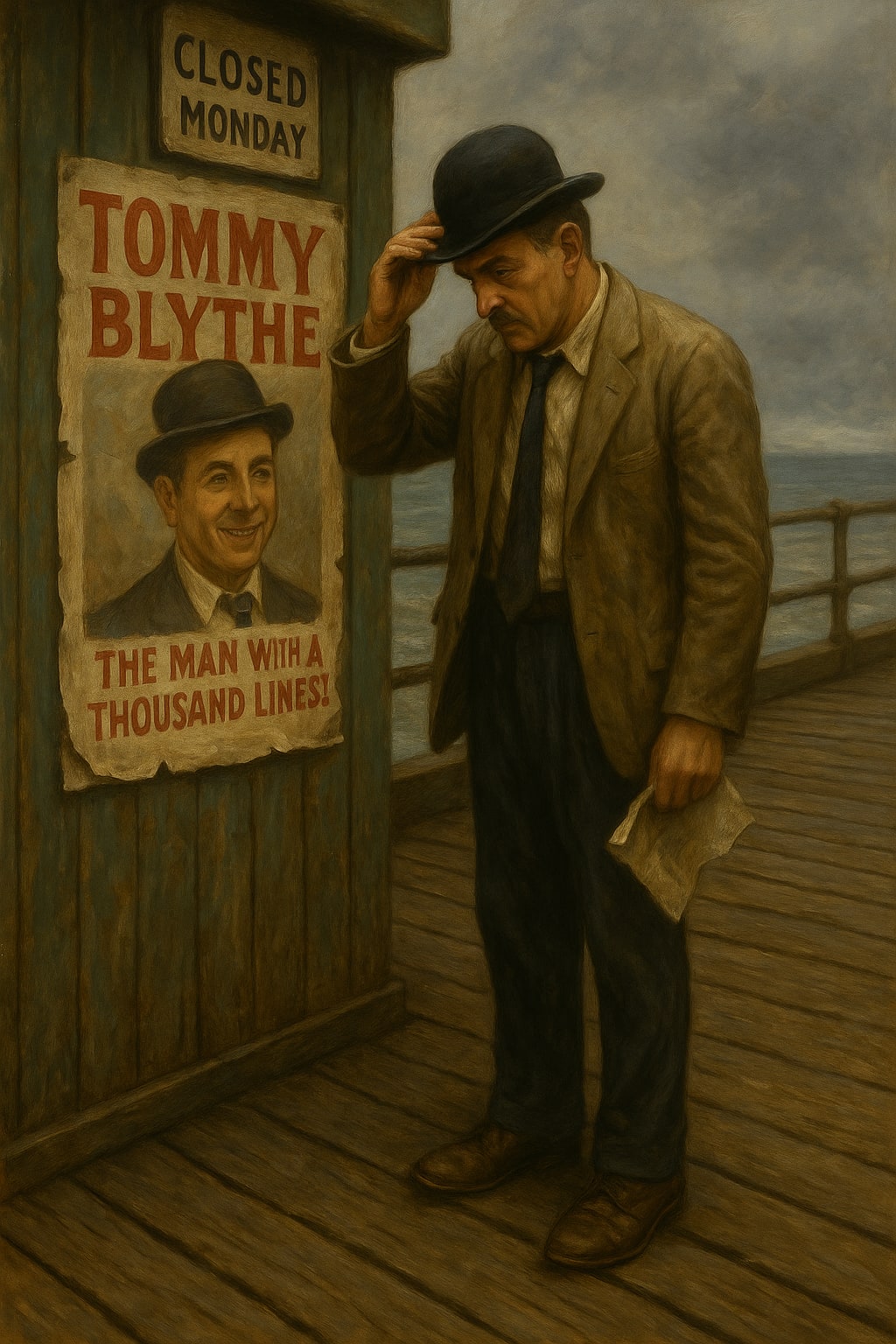

He was halfway to the stage door when something caught his eye — a curl of paper sticking out behind the notice board marked CLOSED MONDAY. He tugged it free carefully, the glue holding on like a memory that didn’t want to be disturbed.

It was an old theatre poster, browned with age and pocked with thumbtack scars. The edges had curled into themselves, but the title still shouted in bright red letters, faded but defiant:

TOMMY BLYTHE — THE MAN WITH A THOUSAND LINES!

Direct from the Palladium. One Week Only!

The photograph beneath it made him pause.

There he was — thirty years younger, sharp suit, sharper grin, eyes like a man who believed in encore afterlives.

He touched the image with the tip of a finger. The paper tore slightly; the ink smudged.

“He looks like he could talk the sun into shining,” Tommy muttered. Then, almost accusingly: “Smug devil.”

He rolled up the poster and carried it to his dressing room, like a man escorting evidence of a crime.

The mirror in the room had known him too long. It reflected everything except mercy. He unrolled the poster and propped it against the wall beside the make-up lights, then sat down opposite it.

“Well,” he said to the young man in the print. “Still at it, are we? Still promising them a thousand lines?”

The silence seemed amused.

“Bet you got applause back then,” Tommy continued. “The sort that filled the gaps where your jokes should’ve gone. You knew how to grin, didn’t you? I remember that suit — had it tailored in Soho. Too tight, too bright, but God, it made me look like I’d been somewhere.”

He poured a splash of whisky into a paper cup and raised it toward the poster. “Here’s to the lad who thought talent was armour.”

Something about the grin in the picture seemed to sharpen under the bulb’s flicker. The face looked almost alive, the eyes full of reproachful laughter.

“You were supposed to make them laugh forever,” the poster seemed to say.

Tommy smiled without humour. “Forever’s been cut back to weekends, lad.”

He took another sip, then laughed — the old professional’s laugh, the one with rhythm even when there’s no audience.

“Look at us now,” he said. “You, a ghost in ink; me, a shadow with knees that click louder than applause.”

The poster, as ever, said nothing. But it didn’t have to.

There was a knock on the dressing-room door.

“Come in before I’m too young to care,” Tommy called.

It was the stagehand again — Alfie, that was his name — holding Tommy’s bowler hat. “Found this in the wings, Mr Blythe. Thought you’d want it.”

Tommy took it with mock reverence. “A man without a hat is just an opinion, Alfie.”

Alfie’s eyes went to the poster. “That you?”

“It was,” Tommy said.

“Blimey. You were proper famous! My gran’s got your records — the one with the ventriloquist sketch.”

Tommy blinked. “The dummy or the man?”

“The dummy,” said Alfie, grinning.

“Good choice. He got the better reviews.”

They both laughed. Then Alfie said quietly, “I want to be on stage one day. Tell jokes, stories. I dunno — something.”

Tommy studied him for a moment — the hopeful eyes, the awkward posture, the youth still unbruised by disappointment. “Then fail early, lad,” he said. “Fail often. It’s the only thing that stays fresh.”

He folded the poster carefully and handed it to Alfie. “Here. Hang it up somewhere you’ll see it when you’re wondering why you ever started. A warning or a wish — depends how your week’s going.”

Alfie looked at the creased paper like it was treasure. “You sure, Mr Blythe?”

Tommy smiled. “I’ve already seen the show.”

That night, long after the theatre closed, Tommy returned. The moon was hanging low over the pier, soft and pale as stage dust. Inside, only the emergency light glowed green by the door — like a lonely applause sign that refused to give up.

He walked onto the empty stage and set a single chair in the front row. Then he pinned a copy of the poster — Alfie had clearly run it through the copier — to the centre of the backcloth. The image looked ghostly in the half-light, his younger self grinning through decades of neglect.

“Evening, ladies and gentlemen,” Tommy said softly. His voice echoed through the empty rows. “We’ve got a small audience tonight, but you look like you’ll behave.”

He began the old act — the landlord sketch, the honeymoon joke, the story about the Punch and Judy man with a gambling problem. Some lines he flubbed, some he forgot entirely, but his body remembered the rhythm. The pauses still knew where to land.

Halfway through, the lights flickered and dimmed — the pier’s power grid protesting the intrusion of memory. He kept going, illuminated only by the little torch in his hand.

At the punchline, he bowed. The silence that followed was enormous — but somehow it didn’t hurt.

“Not bad, lad,” he said to the poster. “You still need to work on your timing.”

Morning came in sideways through the cracked blinds. The caretaker found him asleep in the front row, hat tipped over his face, mouth open in what might’ve been mid-laugh.

“Mr Blythe?” the man said, shaking him gently.

Tommy stirred, groaned, stretched. “Didn’t hear you come in. You miss the show?”

“Show?”

“Good,” said Tommy, straightening his tie. “It was my best audience in years.”

He walked out into the daylight, blinking at the sea’s unhelpful brightness. The gulls screamed like critics, but he tipped his hat to them anyway.

A few days later, Alfie found a note pinned to the notice board. A new sign had been added just beneath it:

NEXT WEEK: ALFIE JAMES — THE MAN WITH A FEW GOOD LINES

Beneath, in slanted handwriting, was the message:

Keep the roof on. — T.B.

The poster of The Old Bill — the one Alfie had treasured — was gone. Only the pinholes remained, two small marks above the title, like eyes closing gently after a long performance.

Out on the pier, the tide rolled in and out, punctual as ever, applauding with a soft hiss against the sand.

Tommy Blythe was gone, but the sound of laughter — faint, stubborn, lingering — seemed to hang in the rafters, waiting for someone else to take the stage.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.