At first light Cole knocks on the door of the shed where the boy sleeps, “Are you ready?” “Im coming Dad” says the boy, opening the door a crack, and sliding out into the bitter dawn. The two pick their way over the hill, and down the other side towards the town. Cole stops for a moment on the hill, adjusts his hat and changes the bucket and rods heavily, from one hand to the other. “Do you have water?” “I got some,” says the boy scanning the horizon. He looks out over the sea with a professional eye. He knows suddenly, that he is looking out at the sea as an old man, with his whole life behind him. It shines beneath them, calm and flat as a mirror, ”It look’s good today Dad.” Cole grunts, and moves off down towards the sea, with the boy following.

On the beach they make their way to a group of dinghy’s, hauled up above the tideline. The little boats are lying on their bellies, looking like dried, salty acorn shells. Their white bottoms arching up to the sky, oars tucked safely under. Cole tugs at a flakey blue one with paint peeling, and motions the boy to get the other edge. It’s heavy. Together they grunt as they heave it slowly over onto its back and look inside. The oars are there, the sawn off plastic bottle is tied on, with the lengths of old rope, coiled neatly. “Looks alright,” says Cole. “You row us out, and Ill row back.” The boy’s shoulders sag. He doesn’t want to row all that way. He thought his Father knew he was only 14, and it is always too far to row. He thinks about Russell, who is most likely already climbing under the bridge, near the river, with his superman comics. As they half-lift, and half-drag the heavy boat down to the water, he thinks of so many things he would rather do with the day.

They push off with the rods, buckets, line and bait stowed. The deep blue, clear water is smooth with hardly a ripple, and for this the boy is glad. The little boat puts its nose towards the sun and heads out across the vast, glimmering expanse. Sea birds call across the echo of the surface of the water. Oars damp with dew, smell of old seaweed and a snail has bravely made its home on one of the paddles. The boy stares at it with fascination as he rows, wondering how long it can cling to the paddle and if he can row with one side up, and other down, and so keep the snail in place. Cole glares at him, “What are you doing? Even, long strokes like I showed you. We don’t have all day,” he grumbles. The boy settles into rowing, warming his muscles up and trying to keep his hands light on the oars and not get them wet. If they get wet they will blister early and he will want to cry, which isn’t allowed. To his mind they do have all day. A whole long, boring day catching fish that jump and fight with them in the boat, thrashing and then spilling blood with their throats cut, and then laying there, in a cold silver pile, waiting to be taken home and eaten. He is bored with fishing. He is bored with rowing and he has forgotten to bring his hat, so his head will be sore later, and his Father won’t care.

The sun glides up over the horizon and radiates beams of golden light, up over the lip of the sea. It spreads bright fingers far and wide, over the gleaming water and all the way up to the mountains beyond. Cole sits in the stern of the boat enjoying the early sun, and the warmth, lighting up his thin, weathered face. To him this is the majesty and beauty of life, all in one simple moment. To be out here, with his boy teaching him how to fish, so that he too can feed his own family one day. They are the lucky ones, to have a house and this boat. They are lucky to be here, not in the big towns where nothing honest can be done. He looks at his son, rowing out across the sea and is proud. ‘I have taught him well’, he thinks, ‘But there is more to learn’. The boat bobs out over the sea. It is carried slightly by the current, which Cole knows will help his son as he rows out. He himself will beat back against the current when they came home, and is saving his strength for that.

After an hour, the sun is high and growing bright. The boy has been rowing steadily, with a firm set to the jawline. Eyeing up the edge of the land and looking at his watch, Cole raises his hand and says, “Here. We can stop. Throw the drogue over.” The drogue is a crude sea anchor that hangs suspended in the water, designed to stop the boat drifting, and keep the bow to the waves. The boy struggles with the wooden bar, which awkward, and buried beneath a pile of frayed ropes. Cole moves over to help and together they throw it over the side. “We’ll be alright for a few hours,” he says, “We’re out of the current.” With relief the boy stacks the oars neatly to one side and flexes his hands, open and shut. They feel alright, and just have one small blister from last time, that refuses to heal.

Cole pulls the bucket to him and begins the delicate job of threading bait, onto waiting hooks. “We need four to start with,” he says happily settling into his seat, noticing the soft slurp of the water, as it caresses the side of the swaying dinghy. The boy looks down into the deep water below them and asks, “How far out are we Dad? Why do we need to come so far?” Proudly Cole smiles, “We’re a mile offshore already, and all the way over the rock shelf. Below us is the edge of the deep-sea canyon, which drops away for nearly a mile below us. This is where the whales come to eat.” The boy has heard all this a thousand times before, but is still curious, “ And why do we come this far out? We don’t want to catch a whale?” “We catch snapper. They feed in the canyon as well.” Taking a long swig from his water bottle, the boy nods. He likes snapper. It is his favourite fish. He only wishes they could catch it in the river instead, ideally from that spot in the long grass, where no one in the town can see him anymore. Thinking about his raw hands and knowing he won’t have to row again, the boy leans over the side of the boat and trails his palms in the cool, dark water.

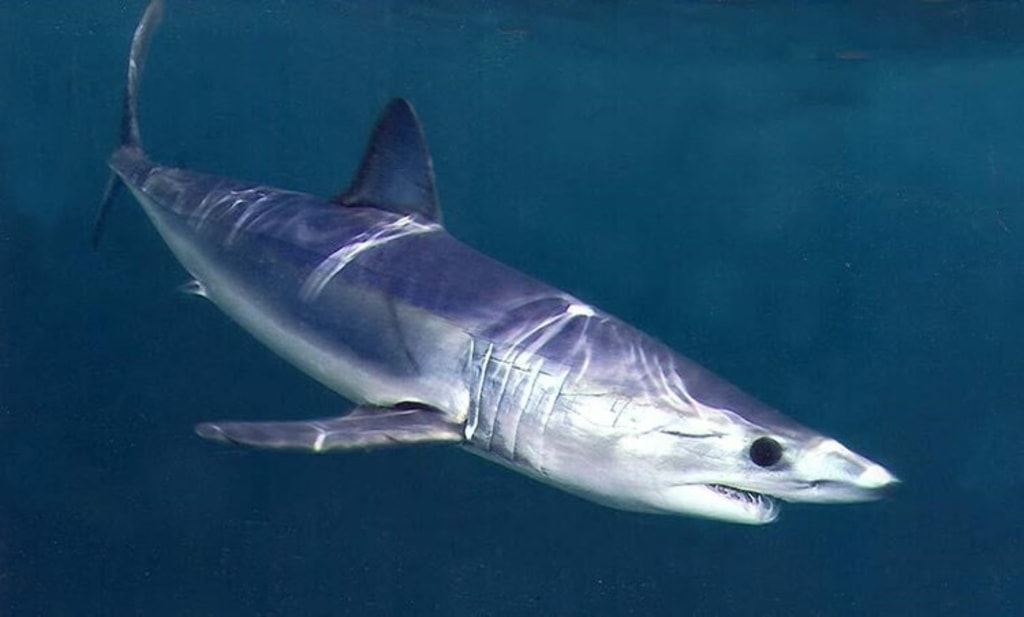

There is a breathless silence all around. It is broken only by the small sounds of his Father, squelching his hand into the bait bucket, and the cry of off-shore birds skimming over the sea. As he soaks his hands and gazes downwards, the boy imagines what it would be like, to swim down to the very bottom of the sea canyon, wild and free. He would see whales, maybe lots of whales playing together. It would be a great adventure. As he stares down into the water a giant, dark, shape glides silently beneath the boat. He can see dark blue spots along the spine, standing out on an inky skin that looks longer than the boat. Maybe twice as long as the boat? Excited it might be a whale, the boy says, “Dad! What’s that?” Cole looks over the edge and knows exactly what it is. “Hands out of the water Walter. Sit quietly now, in the middle of the boat. Don’t move until I tell you.” Cole drops his bait hooks and leans slowly over to pick up an oar. “What is it Dad?” “It’s a Mako shark, Walt. A big one.”

They both sit ridged with fear, watching the surface of the sea around them. Suddenly a great, inky fin slices up through the water a few meters from the stern. The shark has turned around, to pass again underneath the boat and is now rising. Father and son see then, its sleek, mottled skin and terrible size. With the flick of its tail it could capsize their boat and leave them floundering helplessly in deep water. If it comes at them headlong it could do the same, or worse. They sit, unmoving, not breathing, only watching as the shark slices away from them, cutting precise waves through the water. The boy imagines the deadly bulk of the beast as it sniffs them out. Them with their raw fish and tiny little boat, so far from home.

Curling around them in a possessive arc the Mako swims through the water, slowly circling the boat. It does not go under, or leave them alone, just swims around staring up at them from the lurid depths of the sea. In these moments the Mako owns them completely. It owns the sea he cuts through and it owns their fate. It owns their lives and it owns their death. Father and son, desperately united, stare back at the shark with grim determination. The boy, knowing he can’t let his Father down, stops imagining going down into the sea to swim with the whales. Cole sits rigid and still. He is thinking of their home on shore, and what they will do when they get there. He sees them pulling the boat back up the beach, and getting the boy an ice-cream. He probably deserves it. After the third, slow, calculating round, the Mako slides down beneath the water and they lose sight of the fin. There is nothing to show where he is, if he is once again below them and planning a deadly assault, or if he has swum away. “It knows where we are now,“ says Cole, “Lets head in for shore.” Afraid to look over the side the boy nods. “How do we get the drogue in without it noticing?” “Ill row off slowly, and you gather as we go. Just bring it in, a length at a time.”

It takes almost two hours to row back. Cole strains at the oars as he beats back against the current, which is fresh and strong in the mornings. They don’t see the shark again. Both imagine it though, trailing along under the water, watching them and following. Cole hasn’t counted on coming in early. He hasn’t counted on seeing a shark, bigger and more deadly than any shark he has ever known. The boy sits straight up in the stern, his face a mask of fear and defiance. If there had been two sets of oars, he would have rowed as well, even if it hurt his hands. Cole pulls them slowly in, and finally they are in sight of the shore, it’s tiny waves nibbling at the pebbles with the soothing sound of stones rolling over each other. Exhausted, they drag the old boat back up the beach. There is still a depression in the stones, where it has laid before. Wrestling the boat over, they lay it back into its small hole, both shiny with sweat and the water streaming off the hull. In silence, and empty-handed Father and son make their way back up the hill, to home.

At first light Cole knocks on the door of the shed where the boy sleeps, “We need to fish today. Are you awake?” The door is shut tightly against him and Cole can hear nothing stirring within. He tries again with a few short raps, this time louder, “Walt? Are you awake?” Still nothing. Cole shifts his weight from one leg to the other and then back again. The light is rising fast, and he wants to get out before the wind catches. The sky is scudded with cirus, spread out in a tapestry of delicate hooks. He knows the morning will be fine, but the afternoon rough. “Walt?” He is getting impatient now. The door stares back at him. Cole reaches out and tries the handle. The door is locked, and for a moment his brow crease deepens. The boy never locks his door. Where is he? He was at dinner last night with the family, as usual, sullen and cheerless. Nothing different there. He pushes through the weeds around the damp, south-facing wall and peers in through the window. The boy has made his bed, but is not inside. Defeated Cole stumps back to the house. “Esther, where’s that boy? We need to go fishing. He’s not there?” His wife looks up from the range where she has just settled a giant, black kettle. She wipes her hands on her apron, “It’s a school day Cole. He’s probably there. He is behind on homework.” Dissatisfied Cole looks out the window at the day he knows he has just lost. Without the boy he will never get the boat out and back again in time. “We’ll have to eat sausages tonight” he says grimly as he stamps angrily out into the garden.

Walter pulls up the extra chair beside Russell at his family’s table, which is filled with a tantalizing spread of toast and honey. A bowl of steaming hot porridge lands in from of him. “Thanks so much Mrs Hargreave.” She smiles sweetly, “Help yourself Walt, its not often we have visitors for breakfast” Getting up in the cold dark morning was well worth the trouble, although Walt wonders how many breakfasts he can get away with before Mrs Hargreave notices, and his Father orders him home. Russell is digging into his porridge, blowing carefully on each spoon before posting it happily into his mouth. Wishing he had Russell’s family, Walt copies him. With every spoonful he makes up a wish. Please let me stay here. Please don’t make my Father come and get me. Please let me stay here… Together the boys eat slowly through the glorious breakfast. Scraping out their chairs, beaming and content, they walk to school.

Walter has a good day at school, and an even better afternoon crawling through the old pipe under the road where they can sit and dangle their legs at the end, just inches from the creek water. He is content to skim stones, and dig up riverweed, while Russell reads the comic. Later, with a deep hunger gnawing in his belly he dawdles home, and goes to find his Mother in the kitchen. “There you are. Your Father’s looking for you.” “I know, “ he stares moodily at the floor,” We saw a big shark yesterday. I don’t want to go fishing anymore.” “It doesn’t matter if you want to, or not, Walter. The fish aren’t going to come and find us here. You have to go. He can’t manage that boat alone.” Walter knows his Mother won’t understand about the shark. He knows he can’t tell her of the deep, aching fear that lives inside him now when he thinks about the sea and all the giant beasts, curling around inside it. Morosely he slides up to the table, a deep pool of dread collecting inside him. “There you are Walt. Dad’s really cross with you, he made me clean out the chicken run,” says Ann flouncing into the room and dumping her school books on the table. “We saw a big shark yesterday. It followed us home.” Ann is unsympathetic. “You have made me behind on my homework.” She scowls and flicks through the pages of her exercise book filled with neat, small handwriting. “I’m not going to go into the scratchy chicken run every day, just because you saw a shark.” Utterly defeated Walt remembers the cheerful, warm breakfast with the Hargreaves. It is a lifetime ago.

Cole steps into the kitchen, raw with sweat, carrying a bunch of muddy carrots. He sees Walter and scowls. “Its your fault we have no food to eat tonight. We missed the catch today. If you let that happen again I’ll take you out of school for good.” The boy stares at his Father with a mixture of contempt and hatred. “You can’t do that. All the boys my age have to go to school.” Cole thumps himself down at the end of the table. He knows what his son says his true. Coming to the only compromise he can, he says stiffly, “It’ll be both day’s in the weekend then. We need to get enough fish for the week.” “I don’t want to fish Dad. I don’t want to ever see that shark again.” Esther quietly puts plates of food down, and asks her daughter to help. The two move around the table, picking up bowls and plates and cutlery and laying them down without a sound. Father and son glare at each other across the sausages and boiled peas. “If you are going to live here son, enjoying your Mothers cooking, you have to work. You can go to school, but we fish on the weekends.” Having said more than he thinks his son deserves, Cole picks up his knife and fork and attacks the sausages, grunting at his food with a bleak dissatisfaction.

Saturday morning comes, and goes. Cole knocks on the shed door. Once again it is barred to him in a gesture of bold defiance. The boy has locked it shut and disappeared. Cole’s boils with anger and stomps over the hill to see if he can lift the boat down to the water himself. Mrs Hargreave notices Walter has joined them again for breakfast. She smiles, makes sure he has enough to eat, and makes a note to call on Esther later that day. Russell, getting used to having Walt around, plans an adventure to South Bay. He is excited about the Mako. He reckons if they scoot around the rocks and look down over the edge where it gets deep, he might see one too. He is prepared to wait, looking down into the water for as long as they need. Walter agrees to come, only if he can read comics while Russ looks for the shark. He doesn’t want to see it again, not even from the rocks, although he would like to show him how big it was. If the shark is still following him there is a chance he could call to it, and it might come. He likes the idea of calling out to his giant Mako from the safety of the shore. Russell thinks it is the best plan they ever had, and begs sandwiches from his Mum.

The see-saw spring balloons into a brilliant summer. Mountains, like a giant row of blackened teeth, bare their rocky crests to the sky and tiny clouds skim, high and light over the top. There is no time for rain. Father and son have settled into a grim routine. Cole ignores him and goes out fishing by himself dropping crayfish pots along the coast, close in to the rocks. He gets Jimbo to help heave the boat in, and out, of the water everyday. Walt takes his place uneasily at the kitchen table, avoiding his Father’s disappointed gaze and eating quickly. Weekends he spends at the Hargreaves. Russell lives in a small room, at the back of an old weatherboard house. His windowsill is an easy climb and Walt sets up a small bed out of blankets in the corner. To Russell, Walter is an adventurer, just like Huckleberry Fin, and even asks if he can call him Huckleberry. The new Huckleberry is thrilled and they both enjoy his dangerous, double life as a homeless gypsy. Mrs Hargreaves feeds him when she sees him. No one talks about the Mako any more. It lives only in Walter’s memory, who thinks about it every day, and every night.

Putting down his cup, Cole looks straight at Walter over the table for the first time in three weeks. “You school’s done for the year boy.” Walter hears the edge of threat in his Fathers voice and is silent. Looking at his Mother he sees loss in her eyes, and knows his time is up. “If you won’t fish, you’ll have to farm. I’m taking you down to work on the farm at Rotherham this summer. There was nothing to say. “We leave at dawn.”

The farm is built out of blocks. Harsh, sun-bleached earth, measured out, beneath a relentless blue sky. Dotted about, dusty green trees withstand the glare and cast their welcome shade onto a parched earth. Walter likes the farm. The food is rich, and there is plenty of it. He likes his tanned, skinny cousins and giant, solid Aunty Ruth. Uncle Richard sends a broad smile his way, and leaves him well alone. He gets a small room off the laundry and is quick to unpack his bag and pin a poster on the wall. ‘I am home now’ he thinks, feeling the turgid nightmares of the last month sink away. He plans to write to Russell and tell him all the adventures, as soon as he has some. The next day, at dawn, the work begins.

They start him off mustering the sheep, over from the back paddock and down the fence line towards the dip. At first light Richard revs up the engine of the quad bike and nods for Walt to jump on. With two sleek sheep dogs, running alongside they race, over the bumpy land thick with dew, towards the horizon, that grows bright at the brow of the hills. It is cold. Walt is tired and clings onto the bike, thrilled at the speed, but missing his warm bed. “We’ll get them down by breakfast,” yells his uncle, his cheeks flapping in the wind.

There are at least a hundred sheep clinging to the top paddock who scatter when they get there. The dogs fan out, stealthily eyeing them up, and in a few quick movements gather them into a confused cluster. Richard whistles, low and keen to the bigger one. Blue-Dog creeps towards the sheep, one deliberate step at a time staring at them with sharp eyes and his long nose. Suddenly the sheep break, and become a torrent of running hooves, rippling down the hill in a great fluid stream. With a yell Richard revs up the bike. They, and the dogs, tear down the hill after the sheep. Near the bottom Walt jumps off the bike to open the gate into the next paddock, and stands out of the way for the sheep to run through. Just before the gate one sheep senses a dog and stops running. The whole flock stop moving, and start milling about in confusion. Walt stands clear of the gate and tries to stand behind the sheep. Richard, panting, tries to get the young dog into position to the flank of group. It’s too late. With a start the sheep take off in the opposite direction, scattering widely and spreading back out over the field. “You see why it will take us till breakfast!” yells Richard, as the bike screeches up to pick Walt up again. Together they all blast up the side of the paddock again to the top.

The next few hours are spent tearing around the field, attempting to position the dogs so that the sheep won’t break in the wrong direction. They are quick and follow each other at lightening speed. Confused and alert, they want to be left alone, munching on the grass where they stand. They don’t know, or care, about the longer grass, more shade and more water in the bottom paddock. Blue-Dog and Flo are clever and hard working. They eventually manage to round up enough sheep to send them spinning through the gate and into the new paddock. Exhausted Walt closes the gate behind the last of them. Richard grins at him. “Breakfast Walt. We’ll get them dipped through after.” It’s just on 9am and Walter already feels wrung out, thin and tired. He is entirely dependent on the huge breakfast waiting for them. Without it, he will surely die.

After a breakfast that delivers on every level, both quantity and quality are amply and lovingly laid out on the broad, homely table, Walt and his cousins are rounded up to ‘run’ the sheep through the dip. The dip is a noxious pit of chemicals through which each of the hundred sheep must, one at a time, make their bleating and protesting way through, arising at the other end, drenched, sick with nerves and looking like a dirty dishrag. Flo and Blue-Dog sit on the sidelines enjoying the spectacle. This is not their gig, and they love to watch the mottled sheep struggle and skitter. The dogs wag their tails, tongues hanging out, panting in the soaring heat that pulls dust out of the earth and bleaches all it touches.

It is the men’s jobs to coax each sheep through the metal run and then shove them into the dip. Not one sheep wants to go swimming, not today, not ever. The men take turns at the front line, planting a solid hand on the rump of the bleating animal and shoving it head first into the dip. Walt finds after his fifth sheep he is already tired, muscles aching, throat parched with sweat pouring down his face. “You can stop at 20 today Walt. Since you’re new.” Too exhausted to care, Walt acknowledges his Uncle with a forced smile, “I hope you’re counting!” he says, more cheerfully than he feels. The sturdy breakfast has already seeped into every muscle of his body. He has used it up quickly. His thoughts are only on lunch. Calculating how much more he might be able to eat in one sitting, Walt shoves another sheep into the dip.

At lunch, which would have felt like full Christmas, had he not known what was coming Uncle Richard announces cheerfully they are doing well with the sheep. “Just one more paddock to go and I reckon’ we’ll call it a day.” Walt feels dizzy and sore. “It’s good to get the extra help. Thanks for coming over Walter. I reckon’ we can build you up this summer.” Walt sees his summer now. Trapped in a backbreaking routine of sheep, cows, bikes, dogs and food, and understands the unique punishment his Father has delivered him into. A lost memory of the shark, submerged and lethal rises into his mind. It is a shred of a thought, no longer holding power, no longer staring at him. Reaching for another steaming scone and covering it in whipped cream with jam oozing off the sides, Walter let’s his Mako go, for good.

As the month’s pass, and the blistering heat of a dry, relentless summer, grips them all in its unforgiving claw, Walter gets strong. Nothing in his short life has prepared him for these days of grinding physical routine and ceaseless labour. He feels like a puppet offered up onto the apron of a tussock covered earth, jerking his way through the days which speed by in a blur of yellow and blue, blocks of time, blocks of work and deep, powerful rest. Surrender. He learns how to rest, deeply, fully and with total abandon. He learns how to eat strong food that grows muscle and does not hinder speed. He learns how to laugh, long and hard and finds a deep, strange joy in his days with this tough family, its wide honest eyes, and rough jokes. He learns how to smell the dawn as it kisses the earth, and how to long for rain. He learns how to play cards around the fire on a Sunday and he learns how to sneak into the library and pick a book from the shelf and scurry back to his lair with the new treasure. He reads mathematics and geometry. He reads science, and adventure comics. He reads old books on boat engineering and bridge design. He reads a book dedicated entirely to car engines. He discovers he loves his four cousins, and his Aunt and Uncle with a rare passion that he cannot describe, much less talk of. He discovers, much to his surprise that he is happy.

Dawn breaks. Uncle Rich pulls up on the quad, and asks Walt to take it and the dogs over to the back paddock and round up the last few sheep. They got away in the night. “You’re good on the bike now Walt. The dogs know you.” Chucking him the keys Rich hurries off, “See you at breakfast.” Walter starts up the motor, which springs into life and whistles to Blue-Dog. Bouncing along he comes wagging with Flo following behind. They stream out over the lower paddock, open and shut the bottom gate and then make their way more slowly over the rutted ground towards the back paddock, which is around the back of the hill. Walt stops the bike for a moment to look at the sheep. They are rough with summer wool and stare back at him blankly. Spread out ears pricked, there are ten of them looking skittishly at the team. Walt can see their work is cut out.

Rolling the bike forward a small way, Walter hears a small yelp and looks down in shock. Blue-Dog has the tip of his tail trapped under the wheel of the bike. Walt pulls the bike back quickly and the dog is free, growling and upset. Jumping down Walter goes to Blue-Dog and attempts to comfort him. The dog growls in fear, jaws wide, hackles rising. Walter looks at him wondering what to do, when the dog leaps at Walter and clamps his mouth firmly onto his thigh, just above the knee. Blue-Dog sinks his teeth into Walt’s exposed flesh and keeps hold. Blood pours into the dogs’ mouth and down Walt’s leg. The boy yells out in pain. Flo whines and scampers around them. Dog and boy tussle on the ground, Walt writhes and tries to get Blue-Dog to let go, which he finally does. The dog curls off, whimpering to sit on the ground and nurse his tail. Walter writhes on the grass, moaning and yelling in pain. With great effort Walt looks down at his streaming thigh and takes off his shirt to wrap around the jagged wound. With even greater effort he gets himself back on the bike. Dogs forgotten, deliberately ignored, he starts the engine and races off over the field. Fuelled by adrenaline and a desperate need for help, Walter makes it back to the farmhouse. Hearing his yells and cry of pain Ruth comes running and helps him inside.

After hurrying Walt to the local doctor who stitches up his leg, gives him some asprin, and pats him on the back saying, “You’ll be right mate,” he gets his leg in a bandage that goes all the way from mid-calf to thigh. The happy result of his brutal and shocking accident now becomes gloriously apparent. He is laid off from all farm work for the rest of the summer holidays. He has an unequalled social status among his cousins. Aunty Ruth feels obliged to bring him food wherever he chooses to rest, and, best of all, he can now devote his full energies to reading. The painful horrors of the accident fade quickly, and Walt wonders why he hadn’t planned something earlier in the piece. Perhaps a broken arm would have sufficed, or a slow-to-heal muscle sprain…?

Dedicating his days to discovering the most comfortable place to rest, eat, and read, Walt finds an old hammock strung out in the yard, between two shady plum trees, ripe with fruit. So begins one of the most delightful seasons he has ever known. He wonders vaguely about the possibility that Uncle Rich will write to his Father, and his Father might come and get him. He remembers the sharp look of guilt and concern on Uncle Rich’s face, when he learned of Walt’s injury and realizes his place on the farm is safe. He wonders about Blue-Dog and made sure to tell Uncle Rich it wasn’t the dog’s fault. Absolved of any guilt, and feeling sure that his holiday is secure, Walter takes up full-time relaxing.

Studying the book on car engines, one day, Walter hears a quiet drone in the sky, way above him. Through the leaves of the plum tree, high up in the air, he sees a small aeroplane making its way bravely across the sky. It is beautiful. The tiny, wing span, is like a bright symbol of hope. He watches it with a sense of awe at it threads a delicate path through the air, flying ahead of it’s own sound, the drone dropping behind. He likes the sound of the engine, and thinks about the difference between a car engine, and an aeroplane engine. Quietly the boy pictures in his mind all the parts of the aeroplane engine laid out on a table, for him to study and wonder at. Limping out of his hammock to stand clear of the tree, he gazes at the tiny plane in open admiration, feeling something catching in his chest, making him expand with happiness. “I made you a pot of tea Walt,” says Ruth strolling over the lawn in her slippers, “How is your leg today?” Walter turns to his aunt, eyes shining. “Guess what Aunty Ruth!” “I can’t possibly guess unless you tell me Walt,” she says smiling, busy with the tray. “I want to be an aeroplane engineer.” “Well you probably need your leg better before you start on that.”

It is late February. Schools are about to start back and Cole goes to pick up his son off the farm. Walt hugs everyone twice before jumping in the old Combi van beside his Dad. Cole notices he is strong and healthy, with new muscles in the chest and shoulders, and has a deep tan that sets of his shock of blonde hair. He also realizes Walter is now 15. Little passes between Father and son on the winding, dusty slow journey up the inland road that curls around the feet of mountains, and dips into narrow gorges, gleaming with braided rivers. Walt tells his Dad of the dog bite, his wounded leg and about learning how to muster the sheep. He drops then into silence and waits for his Dad to respond. Cole grunts as he stares through the cracked screen at the road, and concentrates on driving. He feels guilty he forgot his son’s birthday, and that he didn’t know anything about the dog bite. He is also worried he hasn’t told Walt about the Mackleroy boys. Eventually croaks out, “I’m glad you learned to muster boy, that’ll hold you in good stead.” Noticing the blank silence that was the effect of his masterful speech, Coles tries again, “Your Mothers’ well. Ann too.” The rest of the journey passes in mutual silence.

Back at home in the shed, Walter re-pins his only poster to the wall and remembers he forgot to write to Russell the whole summer. ‘He’ll be annoyed with me’ Walt thinks ruefully going in to greet his Mother and sister. They look the same. The house looks the same, ‘but I’m different’ he thinks bravely, sitting down at their old kitchen table with something of nostalgia. The family get through a quiet dinner together, only Ann chatters. She tells Walter all about her new friends and the movie theatre that has just opened. Later Walt slips out and climbs into Russell’s room over the windowsill, which seems smaller than before. Startled Russell stares at his friend with wide eyes, “Huckleberry! Your back! You look brown.” Walt notices that Russell has a whole wall of posters and a pile of new comics beside the bed, “I don’t need to stay Russ. Just want to say sorry I didn’t write.” Russell let’s Walt rifle through the comic book pile, instantly forgiven. The two lounge about reading until the light fades from the deep summer sky. “I’ve decided to get a job,” announces Walt pulling himself up so he can shimmy home, over Russells' window ledge. “What job are you going to get?” “Dunno. I’ll find something.” “I’m going back to school. Mum thinks I can learn to work in the bank,” says Russell apologetically. “That’ll suit you Russ. You’re good at numbers.” Huckleberry waves a cheerful goodbye, as he gauges the jump from the outside ledge to the ground and slopes away home, winding through the Hargreaves garden, and around the back of the old train yard.

The day before school is about to start back, Walter arrives in the kitchen and impatiently waits to meet his Father. Esther is busy, whistling a tune as she stirs a large pot on the stove and peeps into the range to see how her bread is doing. Cole stamps in, on time as usual, but empty-handed. “Nothing from the garden today Etty,” he says, avoiding eye-contact with his son. Walter stirs in his seat. “Dad. I got a job today. Soon as my pay comes in, I can buy us food.” Cole stares at his boy, his son, now grown up enough to get a job without him and is speechless. “What job did you get son?” “I got a job out the back of The Whaler, Dad. They get me to scrub the stickers off the old whisky bottles and turn them up new. Then they put new labels on them and sell them as something else,” Walter is aware he is jabbering in his excitement and pride, “They give me a sixpence per bottle, so I that’ll be enough to buy us fish and other food.” Cole looks up at his son with tears in his eyes, and, as usual fails to speak. “Say thank you Cole, you old devil,” prompts Esther. Cole reaches out and takes his sons hand in a warm grip. “I’m proud of you son for getting a job, but I want you to go to school,” he says, managing the long speech smoothly. “But how are we going to get fish?” “I got some help while you were away Walt. The two Mackleroy boys are fit and they have been rowing out with me.” “Luke and Derek have been out fishing with you?” “They have.” “Did you see the Mako?” “We haven’t.” Walter absorbs all of this information carefully, “So you think I should do fifth form?” “I enrolled you already.” Fresh and full of courage, Walter blurts out, “I want to be an aeroplane engineer Dad.” Cole looks at his son with a rare hint of pride, as the unfamiliar wrinkles of wonder, and joy crease up his old eyes, “Then I reckon we should enrol you in the Airforce, when the time comes, Walter.” “

Did you ever go out fishing with Grandad again, Dad?” Father and daughter pick their way slowly up the hill, overlooking the town. Walter stops for a moment on the hill, adjusts his hat, and squints out at the sea shining like glass beneath them, calm and flat as a mirror. Reading her lips he says, “Yes, I went out with him when I could, on the weekends.” “Did you ever see another shark?” Walter carefully lowers himself to sit down on the bench that has been built half-way up the hill, “That was the only time. We didn’t have life-jackets in those days, just us in that old wooden boat. This is all more than sixty years ago now, but you should have seen the size of it Em. I’ll never forget the day we saw the giant Mako.” Emily sits down beside her Dad on the bench, overlooking the dazzling view of the bay, stretching blue and vivid all the way to the mountains in one side, and beyond to a wide, endless horizon. “What else can you remember Dad?” He stirs, and picks up on the few words he can catch. “Well, I used to do some lawn-mowing for a mate of mine’s Mum. Now there’s an interesting story. I read a book about her Father jumping out of a moving aeroplane during the first world-war. 1917 I think it was. Well, you wouldn’t believe it but he climbed out onto the wing of the bi-plane when it touched down, and then jumped, tumbling to land on his feet on the ground. Not a scratch on him...”

About the Creator

Emily Buttle

EMPRESS Stiltdance is an international stilt performance company founded and directed by, NZ born, Emily Buttle.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.