Flash Fiction 7.31.21: Sweet Talk of the Lived

If not with my first grandson, who else can I tell my triumphs?

PART I.

Life ain’t sweet grandson. At my age all my senses betray me, acting on memories, uninterested in my will, or the time on my wrist. Sound and sight were once my trusted accomplices, confirming instinct and action. But now, the sound of a freight train crack-cracking along, sends my mind echoing back. I get by, ignoring that, but it's the hiss, the whispering end, that makes me.

I love you, the questions don't come out easy, but your face says it all, it's loud and unscarred. I know I'm rollin, but If not with my first grandson, who else can I tell my triumphs? Dem? They all tired of me, and the niggas I lived it with — well they, they slow walkin or aint talkin anymore. So who else who, but ya, a lion himself. Who else would sweeten my cup by hearing me tell it? As true, a true "man’s” story can be. A story of two men lying on the railroad.

---

A lie used to cost more, back in the day. Even a white lie, like for fun, could cost ya more than an arm and a leg. On my first day at the quarry the Forman told all the rail workers, just how much it cost them anytime a worker got drunk on the job, and explain’d to me, eyeing my face, that my body had a cost. When the Forman said "boy", I knew it was for me and he'd hold that “r” in that way, ya know, when he's say "workers". He wasn’t much of a man beyond his height, one of the many God given advantages he received instead me. How he would passed over me, looming, to let me know he barely thought me a man. I was new to rail work, not workin, so it ain’t bother me at first, but I wasn't the only one who noticed, and didn't care.

Back then, hell and even now a man ain’t a man without a job. People turn on ya when you weak, but people treat ya like you ain't there if you ain't got a purpose, a trade, a way about ya. “Ain’t I a Man, grandson?” We did man’s work young back then. Back then in summer, honeysuckle made the air sweet, the heat, made men either mad or lazy. So, sweet or otherwise, having a trade, made you a man, kin and a friends. My dad, your great grand, was a man, a sweet man, born during the harvest moon, and raised me for as long as he could. Being a recently freed man He taught me the land, community, and survival. The veteran in’m made him steadfast. When he passed he left me rich in lessons like, “don’t be too loud”. It would take me several years before I realized I was a freeman too and could make my own rules. You see grandson, his lessons were meant for men who were measured and who labored as beast of burden. Yes exactly, men, women and children treated worse than pets. You can imagine from my dad, to me being a man was all one could hope to claim. Speakin of, grand boy, go-get me that vodka bottle, and tell ya ma to spin up a drink for me.

---

Now then… what now, you say you want to hear more about the railroads?

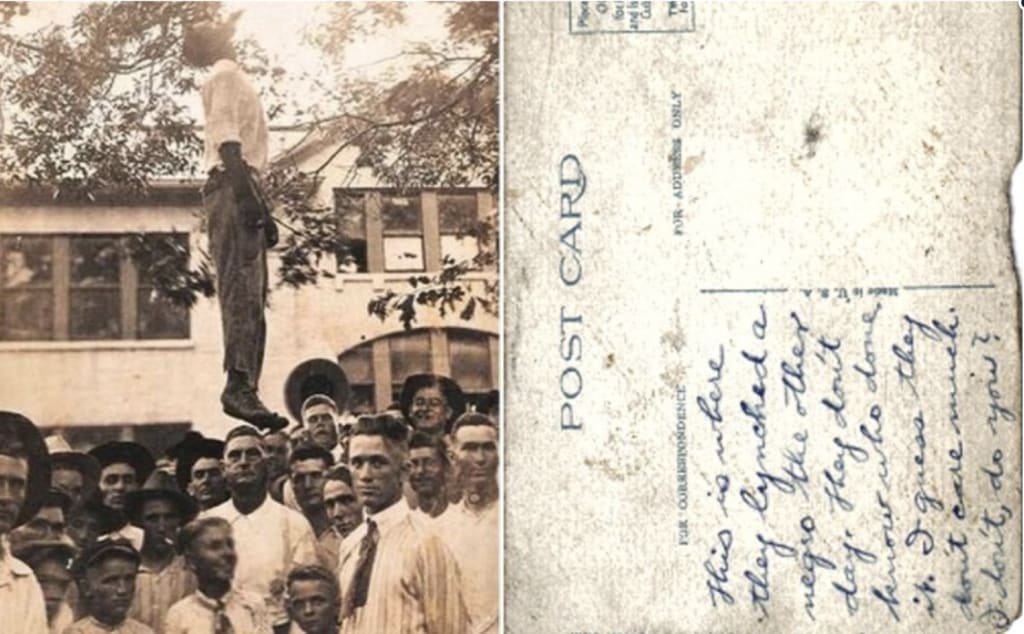

Rail work was good money, and at 15 I fed up with picking peanuts. I had lied on my papers, trading a few jugs of my maple fire water for forgeries. A cheap lie, cost me nothin compared to the unlucky nigga found with his wallet still attached to him. His body was found under a pear tree. His wallet was the only part of him left untouched. I saw the picture of him in the news paper, bout two weeks before I got his ID papers. His neck, appeared more connected to the noose than his husk of a body. The picture, appeared to have ripped clothes, signs of a man in struggle, but the news said "suicide." The lynching, as I saw it, barely registered as an event worthy of the white man’s attention or the cost of making postcards to remember it by. I remember ripping the picture out the paper and folded that picture up, a thin lifeless print. I carried that picture everyday, it was un my pocket that day with the Forman; along with the forgeries, all stacked together. A bunch of cheap lies meant to make me a man, with a job, and lie worth living.

The Forman liked to scare us into workin clean. He-say,“You lose an arm you lose a days work!” “You lose a leg to the rail, we all lose a days work!” “You lose your life, then the rest of y’all get a raise”, he'd say this every day, and everyday he'd stopped pacing, facing perpendicular to me, and I knew that last scare, was just for me. Back then, white lies about murder had gave me a lie of my own to live and I made somethin wit it. Back then a lie gave me a job. Back then. A job was the price. Back then taking another mans life was cheaper.

PART II.

Rail work ain’t for the sweet. The labor is cheap, and the conversations burn my ears more than the August noons.

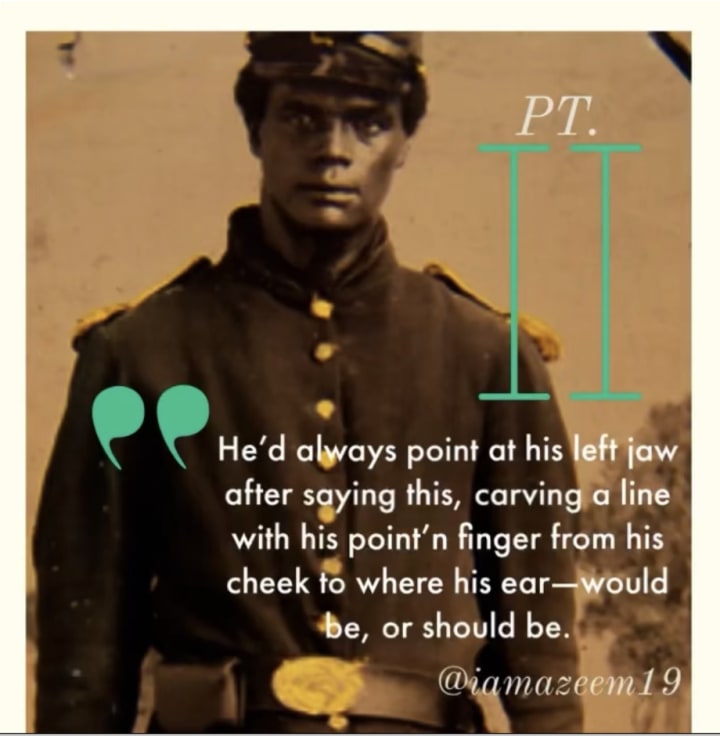

I wasn’t much of a talker. My daddy taught me before passin, “white folk don’t care for you, and they don’t want your words to be too loud.” He’d always point at his left jaw after saying this, carving a line with his point’n finger from his cheek to where his ear—-would be, or shouldda been.

He’d do this every time, like a ritual or prayer. I never liked that, he knew it, still these were the second-to-last words he told me before he passed. He’d try to sweetin my heart with his jig-saw smile, right cheek, a sharp-scythe-like Onyx curve of a smile, the left side a lived man’s receipt of triumph over a nation willing to cut him down to 3/5th of the whole. I never liked that either. He’d smile with the whole of his face, and I swear when he passed, after sayin his last piece, his face, well it glowed! A jumbled mix of skin and scars, all bright and glistenin. That was ok, I didn’t like it, but it was pretty enough that I smiled too. He’d lived a life.

---

Oh right, the railroad story.

That day, on the rail, carrying another man’s life in my pocket, I smiled thinkin of how he lived.

“You must like this work, huh nigger?!?” “Why else you showing yo teeth, you a dog?!!”, these were the words of a man who worked most of the mornings and well into the day with me. See the men still drank, they just waited for the Forman to go inside as we cleared path, and laid rail from 4 am to 2 am.

I gave them the liquid-lighting, the first brew was sweet pear and maple. The pears came from the orchard about a mile down the road. I knew gettin them drunk was risky, but I figured these men, bigger and stronger than me, would be more sweet if I kept’em drunk. I was still young, and pickin fruits from the land ain’t the same as pounding iron into it.

My instincts said to out work’em, move down the trail-- keep em sweet, and get out early. Keep my job, and keep livin. His first jeer was one of many shots. What dat‘man said between swigs of my copper colored concoction gave me more than a ear full to consider. See my instincts also said, "watch that one."

“Hheeeyyy pup, fill my cup quick, before I get too thirsty” he belched. It was sundown and I’d ignored his volleys. They were surface level, I imagined inspired his words as, whispers made by my whiskey in his mind. The day went on, and I eventually convinced myself that I could enjoy the work. And the jaunts over to fill that Drunk mans cup, kept me from sipping myself, so I felt sharp in case things changed.

Cheap men like us don’t get paid to talk, but white men know they lies be worth more than a niggas life. That was something the Forman made clear. After all I got a job cause it sold the lie, "that nobody got hang". It was late evening now and most all the men but us two had gone home. So when that Drunk said what he said next, I knew he wasn’t sweet like the other boys. We’d worked down the path and only had the light of the full moon to guide our hammers and nails. Alone, with a stranger I kept workin. I guess he found something to not like about that, more than he liked my spirits.

“You know I oughta line you up again, like the other night” he spat. “Yup-“, he growled. Then trailed off, “this time, you fittin to die for good.” Of course had there been other men around to hear this they’d call it a bit of drunken musing. You kids call it “venting”, right? Dat what one would assume I guess. Through all the acting as a dead man, responding to another niggas name, and being smooth wit the hooch I had failed to give a face to any of the voices. So when this man pounced on me, or at least promised a pouncing it felt more like a haunt than a threat. And like most spooked folks I laughed out a reply.

“Sir, you still thirsty I see,” my hands grandson, never shock but my voice rattled, “I got a bottle behind that old dogwood tree,” he flinched to look at the tree. And in the moonlight I saw a cursed smile curling up his cheek. Grandson, I’m sure you can guess, I didn’t like that.

Now grandbaby, don’t forget what I told ya. Life ain’t sweet, unless you make it so. Some men never learn how to work it. They can’t see how the salt in their sweat is an offerin to a land that hold us upright. Men who curse the sweat in their eye feel the land and life owe’m somethin. White men above all others, they’re ignorant to what they sow, but reap all the same. Grandson what I say next ain’t for ya ma to hear, ya heard?! You may be new to this, but I see it in ya, you true to it; you den-seen it before, huh? You’ve heard it for real? How they track you with their sights, and tag your ears with that word. Nigger. It’s a spell, I swear it. It tethers you to them. I swear it’s a summoning spell. Like the way my corn wine exposes and exercises truth. Well that word, revives something in me. It peaks something, planted by my father in me, and by his Mau Mau ancestors in him years before I was a thought.

Now my ears ain’t sweet, I’ve known words more sour than dogwood berries. But that one, it ain’t a pet name; not then or today, ya hear grandson? It’s a fraternal call. It’s what, them think, makes their lies and lives special, pricesless. Or more so, it’s like calling black folk Nigger make us somehow different, but also more familiar. For them I think it’s a call for what they believe is the natural order. Like God came down and named them the New Adam, and naming us Nigger is their holy charge. For them, it’s a righteous burden, that they must anoint us with a name. That burden, like all manifested destinies, comes with a cost. A cost they ain’t used to payin. So when he summoned me with it, demanding more hooch I felt myself trip in place, recover, and settle into my role. He laughed, cause he could feel me in conflict. This wasn't his first summoning.

With the full moon to his back I could barely size him up. That laugh, I can still feel pullin my ear hairs. A laugh like that sticks and ignites other memories of the same intent. I could hear in the the gruff of his giggles, a bit of nervous anger. Even with my back to him, pouring shine into a tin cup, that laugh, it sparked something in me, that laugh it was illuminating. This man had a price he wanted me to pay. The price of a name. A name he and his God intended for me and all my kin. It was gonna cost me more than hooch.

“Yooouu think you smart!?!” he dragged. I could hear the gravel tumbling down the side of the rail-path as he edged towards me. “Hey Nigger, that’s a question?”

“No sir, mostly happy to have a job and pour you this here lightin,” I chirped and as the words left me, so did my fear of what was to happen next.

“I ain’t never seen a nigger smart enough to die and come back a few weeks later, new neck an all.” he snipped at me, seeming indignant. “In fact, my god told me one one man can rise from the dead,” he stated before performing a hiccup that seemed to posses him and stop his approach in its tracks. “I heard the Forman call you," he swallowed, "him,” this he said in a steady tone. He meant that dead negro I was carrying in my pocket.

In that moment, even as he faced me, I could only see speckles of his ivory skin, towering over me underneath the tree. I had been tracking him mostly by his hammer swings and sly comments, imagining his full stature. But now I could round out the edges of my ordained god. I could tell he was a modestly strong man who knew how to swing a hammer, but only now, in my crouched position, was I able to take in his full presence.

Under the trees shadows we were both blacker than God intended, but he appeared to have doubled in size under the moonlight. He floated toward me. I stood up. I bridged the gap with my outstretched arm, handing him hooch, head slightly bowed. As he accepted my offering, he turned slightly, eclipsing the moonlight. I could only hear him smile, and as he smiled and sipped, head tilted back drowning himself in the last of my lighting, I brought down the thunder. And as I poured his cup and looked up at his hateful face, I heard my father’s final words. The words that stilled my hands. Revealing a rock in my back pocket I had picked up while pouring, I swung. The sound of his jaw cracking resembled the chaotic chorus made by shattered glass, or the cracking of air as the freights sling by. Second came the tin cup, rattling down to the ground, last came his final hiss, a simple sigh, soft and distant.

That man lay under the rails and his cut was given to all the men but me. Forman claimed he could smell the hooch on my breath and docked my pay according to his sense of justice. What did he say? "In the end everyone got paid on time, and the men with lives lived them."

His last words? They were, “You have to live with the choices you make in life.” And you know grandson, I do like that one. Now sip some more with me, it’s the least you owe me for the sweet life you live.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.