The Voices of Guidance, or the French “Pardon”

“Pardon”

Whenever I do something questionable, I hear a chorus. My aunts, neighbors, older relatives, kindergarten teachers, and school tutors as if the entire courtyard of my childhood lines up before me, arms crossed, watching. “Don’t do that.” “That’s not how you behave.” “You’re a girl be careful.” “Don’t talk back to adults.” “Always ask first.”

Their voices carved themselves into my memory like metal shavings they didn’t kill me, but they stayed, glinting whenever I face a new choice.

As a child, I thought grown-ups knew everything. They surrounded us with a fence made of care and control. Back then, I rolled my eyes at it. Now, I’m grateful.

The other day, my friend and I were sitting by the Rhône, sipping lukewarm coffee carried on the wind from a riverside café. I was venting about how I once again said yes to something I had no time for. She listened and finally said:

— You’re like Gerasim.

— Gerasim?

— From Turgenev. You silently carry everyone’s burdens. You agree, even when it harms you. Just so you won’t hurt someone else.

I laughed, but it hit me like a stone. Like Gerasim. That’s exactly me the silent “yes,” because I’m terrified a “no” will make someone walk away, love me less, or grow cold. How many times have I chosen “wrong” just to avoid upsetting someone?

— Do you think I need to learn to say no? I asked.

— No, she smiled. You need to learn to say yes to yourself.

Her words intertwined with the voices of my childhood: “What is good and what is bad?” We memorized Mayakovsky’s verses as if they were the multiplication table of morality. But adulthood blurred the lines what is “good” for others can feel “bad” for me, and vice versa.

I remember the moments vividly.

Kindergarten: I reach for paints, and the teacher bends down, whispering, “Ask first if you’re allowed.”

School: our literature teacher makes us stand in rows and recite Mayakovsky “what is good” echoes like an oath.

In the courtyard: my aunt, with flour-covered hands from baking bread, pulls me back from the gate: “Don’t follow the boys, girl, I’m telling you!”

Each “don’t” is a red line. And when we grow up, the first thing we do is cross them. Just to see what happens. Sometimes nothing. Sometimes the consequences catch up years later, whispering why those lines existed in the first place.

Now, I have children of my own. I hear myself speaking their names with the same tone my elders used for me:

— Don’t interrupt your father.

— Greet people first.

— Don’t touch papers without permission.

I even scold the cat: “No jumping on the table!” and then laugh. Yes, there it is adulthood. But along with it comes responsibility. Parents lay the soil. However you plant the seeds, that’s how the young soul will grow. I see it clearly in one child sprouts patience, in another the weeds of impatience, in the third, a sharp sensitivity if I raise my voice. Our words water these plants daily.

When we arrived in France (after Italy, after Lebanon, and long before that from Kyrgyzstan), the first thing that struck me was politeness. In the airport, someone brushed against me with a suitcase: “Pardon, madame!” On the bus: “Pardon.” In the store: “Excusez-moi, pardon.” On a narrow staircase in an apartment building, five people passed me one by one, each saying “pardon,” as if chanting a blessing.

I was used to greetings and thank-you back home; we were polite, yes. But this was something else a politeness elevated to a ritual, like a social glue holding everything together.

A few months later, I caught myself saying “pardon” fifteen times a day. Even when it wasn’t my fault. Even when I was the one pushed aside. And I liked it. It felt like a kind of softness I wanted to keep in my own system and pass to my children.

Sometimes, when we walk down the street and my child bumps into someone, I whisper:

— Say: “Pardon, monsieur.”

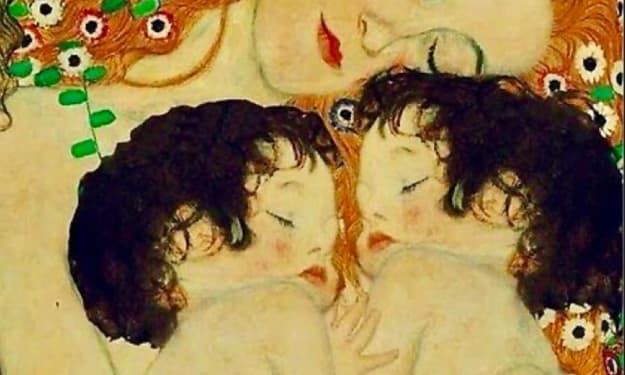

And he repeats it. I can almost feel the cultural roots expanding inside him Kyrgyz roots, Lebanese branches, and now a French flower of politeness.

But France teaches more than courtesy. It teaches patience.

Back home, documents were processed in “two or three days, a week at most.” Here files, emails, letters, “we’ll write to you,” appointments a month away, then rescheduled. At first, I fumed. Then I laughed. Now I come to the prefecture with a book in my bag.

Not long ago, a woman ahead of me in line asked:

— Have you been waiting long?

— Three hours, I smiled.

— Ah, then you’re almost French! she laughed, letting me go ahead.

Waiting is its own form of education. It smooths the edges of impatience, teaches planning, teaches respect for another’s time. Sometimes I wonder maybe the entire system is built this way so we learn how to live together?

Of course, there are no perfect adults. I see people throwing trash, arguing in queues, breaking simple social rules. Each time, my inner judge rises… but then I remember: I have no right to judge. We each carry our own history of guidance. Our own Mayakovsky. Our own Gerasim. Our own red lines.

That evening, my friend teased me again.

— So, how’s my Gerasim?

— I’m learning, I said. Sometimes I say no. Sometimes I just say “pardon.”

— The trick is knowing whom you’re apologizing to yourself or others.

— Can it be both?

— Sure, if love is there.

I watch my children and realize they are growing inside many cultures at once. My job isn’t to crush them with this richness but to help them hear its music. I want them to know: politeness isn’t weakness, boundaries aren’t cruelty, and the question “What is good and what is bad?” is one we keep answering all our lives.

And if one day my children raise their own, I hope their voices will carry all of this: the warm courtyards of Kyrgyzstan, the firm lessons of teachers, the shadow of wars, the patience of French queues, and the soft French pardon that makes the world just a little bit kinder.

About the Creator

Rebecca Kalen

Rebecca Kalen was born and raised in Kyrgyzstan. After graduating from the National University, she worked as an English teacher and later in business. Life led her to choose family over career, a decision that shaped who she is today.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.