Jessa was raised by ghosts.

Her great grandfather, Gino Della Nebbia, and his great grandfather, and grandfathers back to the 1200's, had formed a long line of callous-fingered iron workers, farmers, and quarrymen in the Tuscan village of Fabbriche di Careggine.

Jessa's great grandmother, and her great grandmother's great grandmother, had also lived in the tiny village, developing their own callouses by moving sheep from one meadow to another, kneading bread, digging gardens, planting trees, and organizing the lives of everyone other than themselves.

Jessa's great grandfather had lived with his family and his cousin Carina - who knew that if you talked to fruit trees and grape vines, they'd answer in a flourish of blossoms - in four small rooms above their locksmith shop in the center of the town. They left on a Sunday in 1947, forever, after the final service at the Church of St. Theodore. The bell had already been removed from its tower and driven in an old truck to a church in Modena.

After don Carlo finished his sermon, the church, the village, and the 147 remaining residents of Fabbriche di Careggine all fell silent. The bell was gone, nestled in hay en route to the city. The village was nearly abandoned, and soon, it would drown beneath a lake of water.

Seven hundred years of kiln dried bricks, olive trees, births, deaths, sheep, arguments with neighbors, lemon-scented summers, replaced by progress in the form of of a hydroelectric dam. Two days after don Carlo's final words, the remaining few residents, forlorn and heartbroken, traversed the rutted road and small arched bridge that led them out of Fabbriche di Careggine for the final time. They could feel, below their feet, the tens of thousands of times their families had walked the path before them.

Between the complicated post-war years of 1947 and 1953, while Italy's monarchy was abolished and communism fell, the village slowly began to vanish. In August of 1947 the flow of water started incrementally and then, with a massive whoosh and roar, the flooding rushed forth at the hands of a man who'd never stepped foot on the narrow streets of Fabbriche di Careggine. High above the town, on the lip of a concrete dam, he pulled hard on a long lever, and over time, the village disappeared under the waters of the Lago di Vagli.

First the cobbled streets were submerged. Then the low-slung butcher shop and grocer. Water flowed through windows where boxes of potted nasturtiums and rosemary had grown. Stale left-behind loaves of ciabatta and pane Toscana floated out of the bakery, turned to sponges, and sank.

Someone had left a blue couch that bobbed around a corner of the locksmith shop like a boat hull until it tipped up on one end and slid into the water, sucking down discarded newspapers, old socks, and a few shoes as it was pulled below. Sometimes there was a tapping sound as water entered an empty house, but mostly, there was silence as the village drowned.

For awhile, only the bell tower of St. Theodore was above water, and then, that was gone too. So much history, gone so fast.

History generally ignores small events. Marco Polo had left Venice to seek Kublai Khan's China, and the Sufi order of Whirling Dervishes was established, as Fabbriche di Careggine was built. Centuries later, when discussions about the dam began, Mussolini was falling out of favor, and the lever was pulled shortly after he and his mistress were summarily executed by firing squad. For 700 years, while the world was convulsing and expanding, Fabbriche di Careggine existed quietly, and then braced to vanish.

The 147 people who'd remained in Fabbriche di Careggine until the end had been moved a few miles away to more modern stucco houses, but they would come back sometimes, following sheep or chickens who were lost and completely confused. On those days, the homesick people and bewildered farm animals would walk slowly to the edge of the unnatural lake, first bumping up against a metal fence, gazing in at the nothingness of blue water, the high dam, their missing lives. In time, even the fence was submerged in lake water.

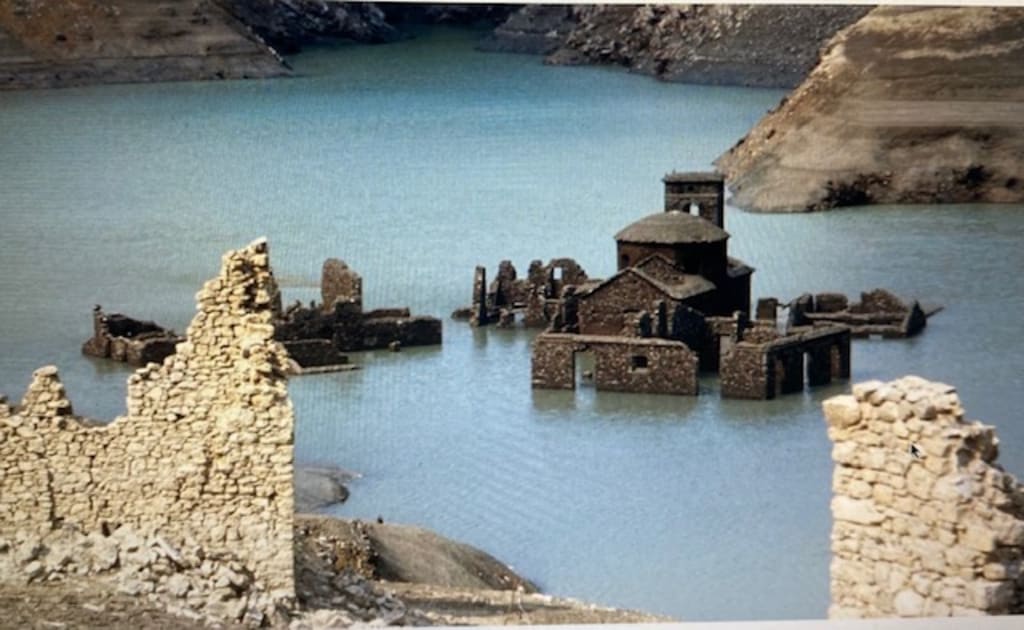

Every few decades, for maintenance purposes, the lake is drained, and slowly, the town reemerges, rising as the water line lowers. First the square roof of St. Theodore's bell tower appears, like a sea trunk floating to the surface. Then its curved windows. The blacksmith foundry that employed men from the village for the entire 700 years of Fabbriche di Careggine's existence presses upward. Waterlogged stone houses begin to show. The chicken coop behind Jessa's great-great grandmother's kitchen pours water from its rocky foundation, where lake weeds have replaced hay in the laying boxes. A rusted wrench, as long as a child's arm, somehow skittered along the lake bed and settled directly under the dam's towering, stilled, waterfall.

It's said that when the lake is drained and the town re-emerges, Fabbriche di Careggine's former dwellers - blacksmiths and locksmiths and marble cutters and seamstresses and sheep and soldiers from the great wars and priests and nightingales - all come back to their homes.

Jessa's Aunt Gina believes this to be true.

"The lake was last drained in 1994," Zia Gina told her. I've heard that this year it'll be drained again. We need to be ready."

"So I've heard." Jessa was sitting on the edge of her aunt's bed, in the small room where Zia Gina had lived for the past 20 years, after retiring from the Ironworkers Union #7. It was only supposed to be three weeks that Zia Gina stayed, at the top of the house Jessa had inherited from her mother 12 years into the 20, but time moves quickly, and things can change slowly, so there seemed no reason to complicate either of their lives.

Jessa's deaf dog Fabbro sat on the floor.

Zia Gina lifted a small black notebook off the table next to her bed. "Because, as you know, they all want to go home now," she told Jessa. "All of them. Every name in this book."

It was true. Jessa knew, because she had lived with these ghosts her entire life, and she knew when they were restless.

Ghosts of sheepherders and locksmiths had accompanied Jessa to school when she was younger, perching on the side of her kindergarten desk, rolling dry erase markers off white boards in middle school, unplugging iPads during sophomore year, the sheep invisibly tripping her competition during cross-country races. Now, they tossed books around her library with regularity.

Everybody knew that she caused the strange events, but nobody knew what was actually happening, or had the evidence to blame her. Instead, they avoided her as much as possible. Jessa's life was a ghost story among the living, and she had garnered few embodied friends.

Every time she ate a peach from the tree in the backyard, a scruffy, dry, urban backyard with only the one blossoming tree, Jessa knew it had been touched, somewhere between its flowers and the day she picked it, by her great-great aunt Carina. And she knew that everybody from Fabbriche di Careggine was living her life along with her.

Her great-grandparents, and Carina, and 700 years of displaced inhabitants who had yearned to hear the bell of St. Theodore once it was no longer possible, had wandered, living and dead, from the moment they crossed the bridge out of Fabbriche di Careggine and left their home behind. Some had wandered as far across the ocean as the small room where Jessa and Zia Gina were sitting, hoping to find a way back.

"They have no home," Aunt Zia reminded her. "Twenty-six generations of our family, and now they have no place to go, so they come to us. All over the world, the ghosts of Fabbriche di Careggine are waiting to go home. Under water, they can't find the bridge. And none of them knew how to swim."

She tipped her head and yelled, "Unisciti a noi!," join us! to an empty corner of her room where she saw a dozen near and distant relatives nodding their heads in agreement. Eventually, Jessa saw them too.

"This year," Zia Gina tapped her finger on the little black notebook and nodded her head, "this year they can go home, and they won't need a boat. I have money, and we both have time. You should have been an iron worker," she added. "The ghosts might not have bothered you so much. They think school librarians don't work hard enough with all that time in the summer. That's why they've always bothered you."

"They threw books around even when I was little, before I was a librarian."

"Yes, but they knew before you did. And I have another life altering book for you." She reached back to the table and showed Jessa a small, flat faded red booklet, like a passport, and in a way, it was. "Old school bank book. This is our ticket to Fabbriche di Careggine. More than enough to get us both there. Because the dead don't need airline seats."

Zia Gina opened the bank book to a page near the end. "We have $20,000, give or take $500 for decent boots to walk in the mud and gifts to leave behind. The money is from selling those old coins I found when your great-great-great grandmother and her dead sheep led me down the beach with my metal detector. We won't be alone."

"All the dead people are coming with us?"

"And some who are alive. Families like us, who live with ghosts, whether we want to or not. With our eyes we'll only see the ruins of Fabbriche di Careggine, but when we sleep they'll show us what it looked like before. We'll see everything that's gone forever. And then, we can leave them. This time, I think they'll stay. And after that, your life might be different."

In early summer, before the peaches were ripe, Jessa and Zia Gina were packed, with sturdy boots, packets of nasturtium seeds, a few peach pits saved from the year before to plant outside the locksmith shop even though they'd never grow, a few folding walking sticks in case lame legs didn't heal after death, and some of the remaining coins that Zia Gina had found at the beach, to give in thanks to her great-great grandmother.

They took the train to Modena and then to Poggio-Careggine-Vagli. There was mud under the arched bridge and along the narrow streets of Fabbriche di Careggine, sticky with receding water and algae. The 'return of the ghost village' had been advertised widely, and tourists carried cameras. But those who escorted ghosts recognized each other easily, as they all turned their heads at the same time and looked up to the tower of St. Theodore, listening to the clear peel of the bell.

About the Creator

Beth Jones

Journalist, educator, author.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.