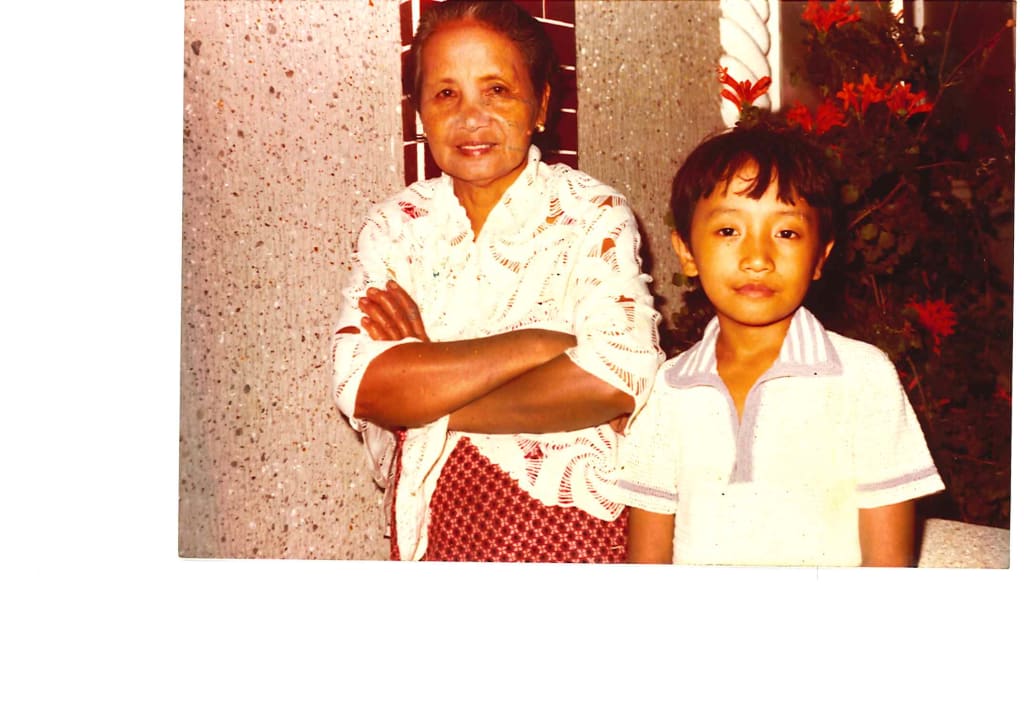

I was raised by my paternal grandparents in a little village called Ulingao in the Philippines. I called my grandma "Nanay" in the Tagalog language which corresponds to the English "Mother". Most people in Ulingao called her "Insong Disya" or “Nana Disya”.

"Inso" was an appellation for the wife of an elder brother. My grandfather was the eldest of ten siblings. “Nana” was a shortened form of “Nanay”. "Disya" was a shortened nickname for her given name Dionisia. I was told that back in her day names were chosen from a calendar listing the names of Catholic saints whose feast day falls on a child’s birth date or baptismal day.

I remember Nanay always woke up at the crack of dawn. So did my grandpa. They were rice farmers. It felt to me that waking up early before the sun rises and consequently going to bed much earlier than city folk was baked into their phenotype.

Living in the big smoke that is Sydney Australia, I’m farthest from being a rice farmer. Yet recently I’ve been waking up at 5 am to meditate, write, stretch my fascia, cook breakfast using my Instantpot and Airfryer, warm up my vocal instrument with my SCSing family, blast through my social media, and numerous possibilities afforded by the quiet alone space and time. Sometimes by 9 am it feels like I’ve already had a full day of being and doing.

I find that waking up this early feels a lot healthier for me. A wonderful bonus is to witness the indescribable beauty of the gradual transition from darkness to the light of dawn, from silence to the noise of the garbage truck doing its pickup, the chatter of cyclists and joggers, and the pop songs of Lorikeets, ballads of Magpies punctuated by the heavy metal blast of Cockatoos and canned laughter of Kookaburras.

Nanay was always doing something. I don’t remember ever seeing her idle or waste time. Even when she was gossipping with the neighbours across the fence I could see she was fishing for useful information, or enhancing the connection and vibe with her quick wit and hilarious, at times outrageously politically incorrect jokes. Nanay could always ignite groups of people to guffaw.

Nanay would feed the pullets, roasters, cockerels, roosters and hens by showering the grounds with unhusked rice, spreading widely so that the pecking order does not disrupt the feeding too much. She would feed rice particles mixed with rice bran to the chicks. While the chickens are feeding she would harvest fresh eggs from the hens’ nests.

Nanay would sweep the fallen leaves on the grounds not with a noisy leaf blower as many do here in Sydney but with a “Walis Ting-ting”—a broom made by tying together long midrib sticks taken from coconut leaves. I remember Nanay buying coconut tree saplings from this guy who was peddling them around Ulingao. I remember she struck a good bargain with the vendor. Nanay was quite known for her haggling skills whether she be buying or selling, unlike grandpa and I who don’t seem to have this ability in our genotype.

Nanay planted the coconut saplings all around the house. The saplings grew to maturity over time and gifted us with seemingly endless streams of coconut fruits, leaves and debris. I remember Nanay asking me to pluck coconut fruits using a rusty sickle tied to a long rattan pole with a wide red rubber band normally used for slingshots.

It was hard. I first had to ascertain from afar which fruits were ripe enough for the picking. I then had to wedge the sickle within the tight space between clusters of fruits, rotate it in a semi-circular motion so that its sawtooth blade on the inside of its semi-circle form comes in just the right contact with the fruit stem then yank the whole contraption up and down in the hope of severing the target fruit from its cluster. As most of the coconut trees were very tall, all these tricky manoeuvres had to be done while I was perched on the top rungs of a ladder leaning on the coconut tree trunk. I did these all the while making sure that: (a) the sickle does not come off its rubber band harness, fall and slash my neck with blood spurting akin to what happens to Morty in his adventures with Rick; and (b) if I did succeed to sever a fruit or fruits from the bunch they would not fall and knock my head off like what happens to Coyote every time he tries to entrap Road Runner.

It would have been easier to climb up the top with a knife and do it there. But I didn't have the upper body strength or nous to do it. Melchor, a real farm boy neighbour not a pretend one like me, could do it quite readily. Nanay did pay him a few times to climb and pick the coconut fruits. Melchor's grandma, Nana Rita, was miffed about this. She got mad at Nanay for this mutually beneficial arrangement. Nana Rita considered this deal as making a slave out of her grandson. A bit over the top reaction but I felt there was something more to that.

Many years before the coconut trees Nanay planted guava trees spread throughout the land surrounding the house. These guava trees gave her a steady cash flow over the years. She would pluck the guava fruits that was close to full ripeness. She used a welded circular piece of steel rod with wavy teeth like bends at the top of the circle. This circular contraption was attached to a long rattan pole. It had a pouch made of fishnet attached around the bottom to catch falling guava fruit plucked from the stem by the wavy steel teeth. This contraption was called "sungkit" in Tagalog. The guava is scooped from the “sungkit” and transferred to a larger collector fishnet bag. Lather, rinse, repeat as Nanay went from branch to branch, tree to tree.

The guava trees grew so tall that the length of the rattan pole was insufficient to reach most of the fruits sitting further up from the ground. So Nanay climbed the guava trees, with “sungkit” and fishnet bag in hand to do the picking. She kept climbing her guava trees until she wasn't physically able to do so. This was awkward for the family. I would imagine particularly so for my dad. He was the first person to get a university degree in the village and transition from generations of subsistence rice farming to office work.

Nanay would put her stash of picked guava fruits into baskets, recycled KFC buckets, and pails. She would stuff the spaces between the guava fruits with newspaper, yellow and white pages. The heat generated by this would ripen the fruits more until wet market day.

I remember Nanay’s wet market day to be on Wednesdays. She would arrange Tata Berting, our go-to tricycle driver to pick her up from the house with her baskets of guavas and bring her to the wet market in the nearby town centre of Baliwag. She would sell the guavas to buyers she had developed long-term relationships with, her "suki " in Tagalog.

Nanay would then use the cash she got from the guava buyers to buy food and groceries from her “suki” vendors. I remember she had a “suki” butcher who would set aside a special portion of “inside” pork blood, meat and offal to make one of Nanay’s signature dishes “Tinumis sa Sampaloc”. “Tinumis” is a pork blood pudding stew soured with tamarind leaves and spiced with green chillies. Paired with freshly boiled rice, this was perfect on tropical rainy days.

She would also buy “Dalagang Bukid” (Redbelly Yellowtail Fusilier) fish. I would see her slicing marks on the sides of the fish to squeeze rock salt in, and set them aside in the fridge. After a day or two, they would be ready to fry in vegetable oil. I remember eating friend “Dalagang Bukid” with boiled rice, fish sauce, and steamed young sweet potato leaves. Salty delicious.

Nanay would also buy “Bangus” (Milk Fish) to cook “Totsong Bangus”. The dish is made by first frying the “Bangus” then stewing it in vinegar, ginger and “Tahure” (fermented tofu with black bean sauce). Nanay showed me the trick of knowing when to turn the fish being fried without wrecking it to pieces in the process. The trick is to look at the sides and see how much the “Bangus” fish meat has changed, starting from the bottom, in opacity and colour from semi-transparent to milky white, to golden brown. When the milky whiteness is halfway up the fish, one can safely check if the fish is ready to turn by first unsticking the golden brown bottom from the frying pan by jabbing the frying spatula on a 45-degree angle between the fish and pan then sliding under 180 degrees horizontally, jiggling the fish then turning over. Nanay told me so many times the protocol for adding vinegar to any dish. She repeatedly said: “Pour the vinegar in BUT do not stir until it is simmering. If you stir before it simmers it would be badly soured, if you stir after it would be deliciously sour."

Nanay’s other signature dish was fried chicken. We used our homegrown chickens. The meat was gamier and a whole lot tastier than commercially grown chicken. She would marinate them in “Calamansi” (Philippine Lime), and “Patis” (fish sauce) for at least a day. She would boil the chicken first in the marinate liquid until dry-ish then add vegetable oil to fry until the skin is golden brown. I remember how much my siblings and I loved Nanay’s fried chicken. We usually ate Nanay’s fried chicken with UFC Ketchup and boiled rice.

Similar to having long-term relationships with her “suki” in the wet market, Nanay was loyal to certain brands. She always bought Blend 45 coffee, Darygold evaporated milk, Patis Malabon, Baguio Oil, Camay beauty soap, Palmolive shampoo, Fanbo compact powder, Johnson’s Baby Powder, Johnson’s Baby Oil, Johnson’s Baby Cologne, Vicks Vaporub, Skyflakes, Sustagen, Ajax Laundry Bar, Tide detergent powder, Chlorox bleach, Bandong’s Coco Jam, and Salonpas Pain Relieving Patches.

Long before I even heard of Costco, I remember Nanay always bought things in bulk. She bought refined sugar in 50-kilogram bags from wholesalers instead of what most other people in Ulingao do of buying in repackaged small half-kilogram bags from the village Sari-Sari stores (akin to bodegas in New York).

She used a lot of sugar to make dessert, preserves, and ice candy. I believe when dad received his first salary as an accountant from SGV (accounting firm in Makati City) he bought Nanay a fridge. This was one of the first if not the first fridge to exist in Ulingao. Nanay soon after started to sell ice bags and ice candy. The business was hectic on hot and humid summer days. A steady flow of villagers would come to use their one peso coin to tap on the flat iron gate welded and cobbled together by Tiyo Peding. They’ll shout out what they want, I’ll bring the ice bags or ice candy, get the money, give them change, on and on.

At night sometimes Nanay would ask to help her out to make ice candy. She would ask me to make young coconut (“Buko”) shreds (“Kayod”) with a hand scraper. Or she would ask me to hand grate (“Kudkod”) mature coconuts (“Niyog”) using a “Kudkuran” - a low wooden bench with a sharp metal starburst-shaped blade attached to one of the long sides. I would sit with the bench between my legs, hold a de-husked halved coconut endocarp with the two hands and grate the solid white albumen within the cavity against the blade using up and down movement then turning when a part has been fully grated. I would then add steeping lukewarm water to the grated “Niyog”, place lumps of these inside a cheesecloth, and squeeze to collect the coconut milk “Gata”. This with evaporated milk and sugar formed the base of ice candy with the “buko” as “sahog” - a floating solid ingredient.

Sometimes Nanay would make Candied Wintermelon (“Minatamis na Kundol”) as “sahog”. This was one of the party treats Nanay was known for. She would make plenty of these with the cut “Kundol” placed inside glass jars filled with the sugary preservative syrup. These jars were then ready to be gifted to birthday parties and other special celebration in Ulingao and neighbouring villages.

Long before I heard of the artisanal hipster picklers in Marrickville, Nanay showed me how to make a delicacy from farm to table. Nanay planted the “Kundol” at the side of the fence so the vine can crawl up the chicken wire. We would harvest the “Kundol” and peel the outer skin carefully. There is an art to this. I had to learn how to peel using a knife just enough to remove the hairy bits of the skin but not too much. The greenish, crunchy part of skin must be left for crunch and colour. After peeling, the “Kundol” is cut in half, the seeds and fleshy bits in the core scraped off. What’s left is then cut with this special knife that cuts them into wavy bite-sized pieces.

Nanay is known for making her “Kundol” super crunchy. Her secret was to soak the “Kundol” in lime (“Apog”) overnight, then to soak/wash the lime off using rice water (“Hugas Bigas”). Another party delicacy Nanay was known for was roast pork sauce ( “Sarsa ng Lechon”). Her secret was to only use roasted pork liver, pepper and spices. Her sauce was special because she did not use extraneous ingredients like flour to extend the sauce, and she took her time making these delicacies.

When we were doing these things, sometimes we would have the transistor radio on. It was one of those analogue portable AM radios powered by C batteries. We would listen to DZRH for radio dramas like Zimatar, “Gabi ng Lagim”, “Tiya Deli Magpayo”, Ernie Baron, Ray Langit, and Rick Radam.

And then there were lots of times when Nanay would tell stories. I tell ‘ya she could yarn like there was no tomorrow.

She told me that in her younger days, she was the forewoman (“Punong Sugo”) for villagers contracted to plant rice seedlings during planting season. The landowner would contract her to have their field planted and give her the budget. Planters would enter and exit the fields at different times of the day. Nanay had to keep tabs on these so she could properly pay these workers at the end of the day. I could feel that people trusted Nanay. She felt like one of those rare people who could hold the line no matter what.

Nanay did not get much formal education yet I’m so much in awe of how she could do arithmetic calculations in her head with such flow and ease. She also kept notebooks as meticulous ledgers of money coming in and coming out of the various entrepreneurial activities she was undertaking in parallel at any given point in time.

Long before I became aware of the word “Feminist”, Nanay told me that she was the only woman among her peers who had land of her own when she got married to my grandpa. She said that when she turned 21 her dad wanted to give her an expensive watch. Nanay told him that instead of a watch, could he just give her one of the tracts of farmland he owned. He agreed. I was told that at that time vacant land was so plentiful and cheap. Our families could have been set for life had our patriarchal forebears had the foresight that the land would have been worth a lot more in the future. Well, Nanay did.

When she was a maiden, Nanay told me that the village witch doctor had taken a fancy on her. She said other women this had happened to got sick and hysterical. So much so that they had to pay another witch doctor to reverse the spells. But not her. She said at night she would see the acacia tree outside her house on fire without burning. Instead of expressing fear, she would say “Oh, someone’s started a bonfire there, I better check it out tomorrow”. When she was in the loo, she would feel hands on her privates. Instead of freaking out, she said she would ask for a lamp and say “there are lizards in the toilet, let me have a closer look.” She would see the witch doctor’s spirit hovering around and outside the house. Instead of shrieking, she would tell her parents “we have a visitor, let him in”.

So long before I learned of the Bene Gesserit Litany Against Fear in the Dune Universe, Nanay has already given a download to my young mind. Looking back, these kinds of stories from Nanay also prepared me for my later explorations of non-physical realities like when we did seances as Spirit Questors at the Ateneo de Manila University.

Nanay told me that once she was invited to worship at “Iglesia ni Kristo” - a prominent Christian sect that originated in the Philippines. She got curious and accepted the invitation. At one point the pastors asked everyone to close their eyes. She did at first but at some point, she said she opened her eyes and saw the pastor checking out the pretty women in the flock. She said she never came again.

She remained a Roman Catholic all her life. She went to church only around Christmas time where it was those rare times she would come dress to the nines, and wear the expensive perfumes she kept hidden and unused for most of the year. Nanay was frugal but not miserly. She abhors waste but can splurge when celebrations are called for.

The most poignant moments we shared together was when Nanay would tell me stories about the times her heart was broken to pieces. I didn’t have the concepts and language back then but now I realised she was sharing her traumas with me. But these I will share with you at another time.

There are so many stories that live in me, in you, in us. I heard some neuroscientists say that we don’t store memories like files in a hard drive. Rather when we remember we engage neural networks similar to the neural networks that were engaged when we first experienced the event. We construct, simulate the reality that was. So as I write this I am recreating the reality of being with Nanay.

I also heard someone say to remember is to re-member, to become a member of something again. When I remember Nanay she once again becomes part of my current reality. Now that you’ve read this perhaps she’ll become part of yours too.

About the Creator

Oliver James Damian

I love acting because when done well it weaves actuality of doing with richness of imagination that compels transformation in shared story making.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.