Goodnight Stories for Multiracial Children:

An Analysis of Multiracial Children’s Books as a Tool for Parenting in Today’s U.S. Culture

Breanna Carter Graduate Student at the University of South Florida

Abstract: This critical content analysis examines two children’s books made for multiracial children that were published between 2013 and 2015 and how they can be used as tools for mothers to guide their children through the racial climate of the U.S. today. These books can be used as tools for mothers of multiracial children to help their children self-identify as multiracial. The theoretical framework used in this study is social identity theory (SIT) (Bilig & Tajfel, 1973; Hogg, Terry, & White, 1995). The results of this study indicate that (1) hair, (2) outside perceptions, and (3) multiracial celebration/positivity are found in the two multiracial children’s books to be used by mothers to help multiracial children identify in U.S. culture.

Introduction

Even though multiracial children have been around for centuries, the multiracial population has not always self-identified or had the cultural allowance to identify as such (Masuoka, 2017). In the past, there has not always been a language available for multiracial people to use to define themselves or to be categorized in formal ways (such as in the Census or on important forms or documents) and the language that has been used has transformed in the last few decades (Doyle & Kao, 2007).

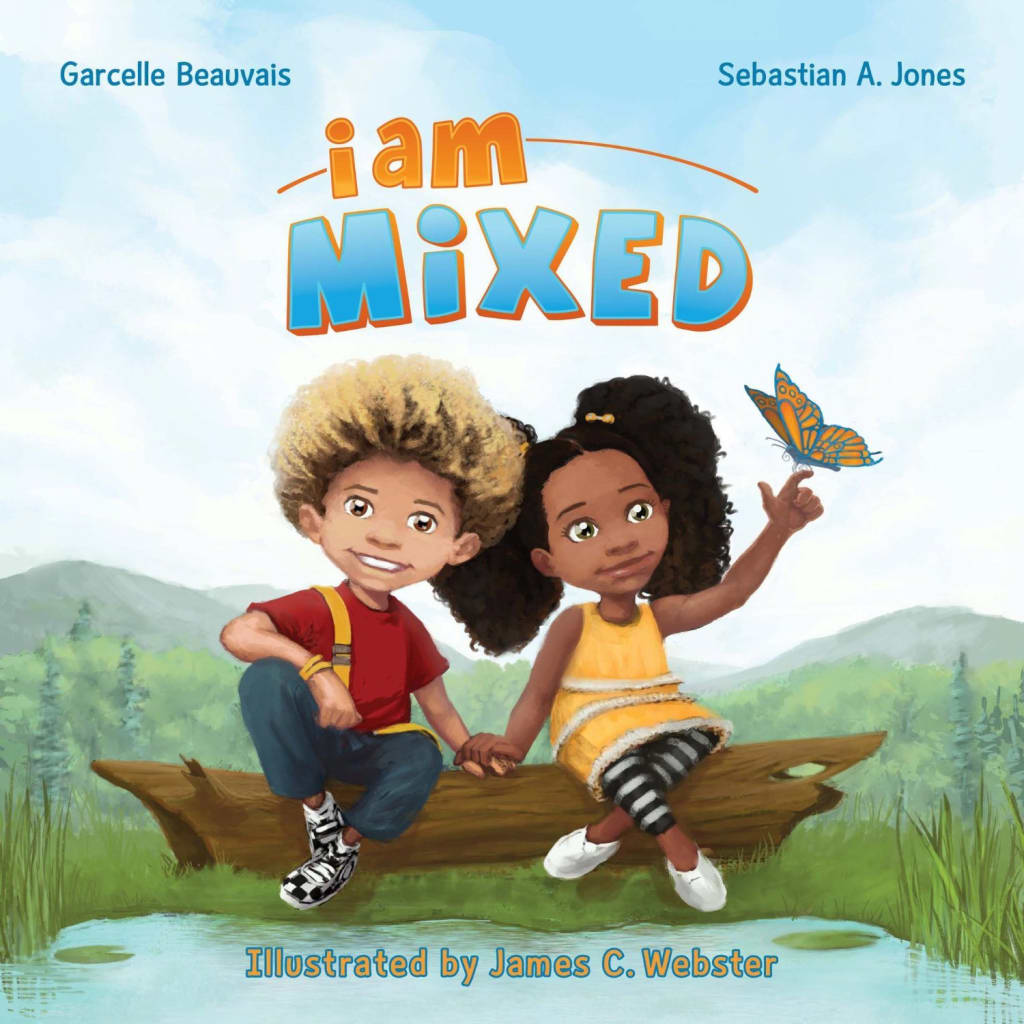

Multiracial children today, arguably have the most space to self-identify as multiracial. Natalie Masuoka (2011) states, “Furthermore, in today’s society that promotes multiculturalism and racial diversity, there appears to be greater public acceptance toward those identifying with a nonestablished racial identity group such as “multiracial” (p. 177). Children’s books shape and conceptualize ideologies, values, and beliefs from the dominant culture, including racial scripts. “When children learn how to read they are also learning about culture” (Taylor, 2003, p. 301). In this study, I will be conducting a critical content analysis to objectively identify the messages about multiracial identities contained in two multiracial children’s books. The books I will be analyzing are Mixed Me (2015) written by Taye Diggs and illustrated by Shane W. Evans and I am Mixed (2013) written by Garcelle Beauvais and Sebastian A. Jones and illustrated by James C. Webster.

Literature Review

Why Do Multiracial Children’s Books Exist? A Brief Background on Multiracial People

Multiracial people have always existed, yet the way that they have been culturally categorized or the way that they are able to self-identify has not always been as multiracial, mixed, or biracial. Biracial children specifically, someone who is defined as having biological parents from two different racial/ethnic groups (Winn & Priest, 1993) who are mixed with both black and white have traditionally been classified as black (Zack,1998). This ideology can be traced back historically to U.S. slavery. In Killing the Black Body Roberts (1997) describes the chilling reality of black women’s treatment during slavery; stating, “Here lies one of slavery’s most odious features: it forced its victims to perpetuate the very institution that subjugated them by bearing children who were born to the property of their masters” (p. 24). If a white slave owner raped an enslaved woman and impregnated her, the child could not be considered white so that they could justify the child being a slave (e.g., Hickman, 1997; Roth, 2005; Khanna, 2010, Patterson, 2013). Golub (2005) states, “Ambiguously raced bodies threaten to disrupt ordinary assumptions of naturally distinct races and thus are met by the law as a kind of problem to be contained” (p. 567).

This is how the One-Drop Rule and hypo-descent became dominant ideologies in the U.S. This ideology from over one hundred years ago continues to transcend throughout society today (Patterson, 2013; Roth, 2005; Khanna, 2010). Not only was the One-Drop Rule an ideology it was also law. The most famous U.S. case where the One-Drop Rule is prevalent would be the Supreme Court case of Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. Homer Plessy was a man with ⅛ African ancestry and ⅞ White European ancestry. Homer Wanted to sit in the “Whites Only” section of a train because the “Whites Only” section was nicer. Homer was white passing did indeed not “look” phenotypically black (Golub, 2005). However, Homer Plessy was arrested after telling the conductor his racial background and it was decided that his case would be used as a strategy for justice because of his racial ambiguity and be taken to the U.S Supreme Court (Golub, 2005). Homer Plessy lost the case and the case famously became known for the “separate but equal” doctrine, but there is more to this case than the ruling. Golub (2005) states, “Plessy’s ability to pass for white (and his publically staged refusal to do so) called attention to the social and legal processes of racial sorting through which purportedly natural and discreet race groups are produced and maintained” (p. 564). Homer Plessy, a man who had two white parents, was still legally considered black. Plessy v. Ferguson demonstrates just how deeply rooted the One Drop Rule and hypo-descent are in U.S. legal systems.

Doyle and Kao mention the One-Drop Rule stating, “First, remnants of the One-Drop Rule persist as a powerful force that truncates identity options for multiracials who have a black parent. This archaic and stigmatized term faded from political discussions after World War II. However, evidence suggests that remnants of this conceptualization of race are still present in U.S. society due to the resonance of legal sanctions in history that legitimized this practice” (p.406). They conclude that this conceptualization of race still exists today.

Harris (1964) describes hypo-descent by stating, “This descent rule requires Americans to believe that anyone who is known to have had a Negro ancestor is a Negro” (p. 56). Omi and Winant (1994) also write, “In the United States, the black/white color line has historically been rigidly defined and enforced. White is seen as a ‘pure’ category. Any racial intermixture makes one ‘nonwhite’ (p. 57).

Today, the research suggests that some biracial children (with African ancestry) are considered black because the outside world would consider them black and not multiracial. Harris (2002) states, “In many situations, biracial children were simply identified with the parent of color” (p. 120). Even if a multiracial person would like to self-identify as mixed race/biracial/multiracial, if their minority parent is brown or black they are more likely to be labeled as that minority race; even though members of that minority race may or may not accept them fully into their in-group (Rockquemore & Brunsma, 2002; Rockquemore & Laszloffy, 2005). Some research suggests that children of different racial backgrounds can experience different phenomena (Doyle & Kao, 2007). They found that multiracial people of Asian and White descent can have more flexibility in choosing how they identify (they can more easily say they are white rather than Asian or multiracial) than those who are mixed with Native American and White and Black and White.

The population of people who self-identify as multiracial has been steadily increasing in the U.S. (Kalish, 1995; Farley, 2002, Masuoka, 2011). The population has been growing since the 1960s after the case of Loving v. VA was passed by the Supreme Court in 1967 allowing legal interracial marriages in the U.S. The multiracial population has increased significantly in America recently due to the growing rate of interracial marriage (Farley, 2002; Harrison and Bennett, 1995; Harris, 2002; Roth, 2005; Perlmann & Waters, 2005). Typically, when people think of bi/multiracial individuals they think black and white. However, multiracial people are anyone who comes from two or more ethnic/racial backgrounds. Lewis and Ford-Robinson (2010) state, “Increases in the Hispanic American and Asian American populations have led to a more multiracial focus” (p. 413). Meaning the rates interracial marriages and dating relationships are increasing across all ethnic backgrounds thus meaning there are more multiracial children and adults in America now than ever before.

The authors who developed racial formation theory, Omi and Winant (1994) state:

One of the first things we notice about people when we meet them (along with their sex) is their race. We utilize race to provide clues about who a person is. This fact is made painfully obvious when we encounter someone whom we cannot conveniently racially categorize--someone who is, for example, racially “mixed” or of an ethnic/racial group with which we are not familiar. Such an encounter becomes a source of discomfort and momentarily a crisis of racial meaning. Without racial identity, one is in danger of having no identity (p. 13).

I must note that in racial formation theory, people tune into race specifically as skin color and are not comfortable with racial ambiguity-- hence the “discomfort” stated previously. Masuoka (2017) additionally states, “Race is not simply an objective demographic category but rather is understood to be a politically consequential statement about the self that implies particular values and attitudes toward American race relations” (p. 147).

When it comes to how multiracial people choose to identify today there is still political and cultural controversy at stake. There seems to be a division among the multiracial population today regarding how to identify (Masuoka, 2017). Some multiracial people advocate for an identity category and believe in embracing both/all sides of their identity (Butler-Sweet, 2011; Masuoka, 2017). While some see identifying as multiracial to be problematic. For example, Leverette (2009) states, “Because many mixed race individuals sought to progress in White supremacist culture through passing as White, those who assert a mixed race identity or who problematize Black identity within of mixed race are often seen as denying their Blackness and/or worshipping Whiteness” (p. 435). The history of race, racism, and multiracial people affects how multiracial people can identify today. How does this history affect the ways in which people who mother multiracial children help them situate their racial identity?

Mothering & Bedtime Stories

In “The Creative Spirit” by June Jordan, Jordan (2016) discusses how children’s literature is integral to the creative spirit. Jordan (2016) discusses how children depend on the adults around them to mold them into who they are/will become. Jordan (2016) states:

“Like it or not, we are the ones who think we know, who believe, who remember, who predict, a great part of what they will, in their turn, think they know, or remember, or believe, or expect simply because we are the ones who feed, who clothe, who train them to stay away from fire or dolls, or Chinese food or the vigorous climbing of apple trees” (p. 13).

Why do parents read to their children? Some studies have found that parents read to their children to improve their child’s literacy, language development, and understandings of images (Smith, 1976; Clay, 1977; Snow et al., 1998; Burgess et al., 2002). Multiracial children’s books like I am Mixed and Mixed Me are distinct from other children’s books because they are solely written for the parents of multiracial children to read to them in order to aid in how their children develop a strong sense of self; while simultaneously preparing their children for the way in which they can be perceived from the outside world. A study conducted in 1999 by Greenbough & Hughes, suggests that parents conversing with children about what they read to them can tremendously help them understand and value what they hear/read. Multiracial children’s books are made to help children understand their identities. Parents who read multiracial children’s books to their children are ultimately creating a space for their children to ask questions about themselves and the culture that they live in.

Multiracial children being able to claim this identity legally and freely is revolutionary. The parents of these children must know that even the existence of such books as tools is also revolutionary. Gumbs (2016) states, “Those of us who nurture the lives of those children who are not supposed to exist, who are not supposed to grow up, who are revolutionary in their very beings are doing some of the most subversive work in the world. If we don’t know it the establishment does” (p. 20). Multiracial children today having the ability to identify as more than just within the limits of the One Drop Rule was not supposed to exist on a personal level or legal level. Children’s books like Mixed Me and I am Mixed are being used by the mothers of multiracial children to help widen a very narrow view of race, ethnicity, and personal identification.

The research suggests that multiracial identification is contextual (Butler-Sweet, 2011; Doyle and Kao, 2007) in that personal experience for multiracial people varies with class, region or location you are raised in, how your parents communicate with you, external discourses about your race (Rockquemore and Laszloffy, 2005), and even your sex (Doyle and Kao, 2007). Butler-Sweet says, “Socioeconomic class also has a tremendous impact on how parents socialize their children” (p.748). Note that having the time and resources to read to your children is a privileged position (Compton-Lily, 2003).

Critical Content Analysis

Beach et al., (2009) describe content analysis as, “Content analysis is a conceptual approach to understanding what a text is about, considering content from a particular theoretical perspective, such as sociohistorical, gender, cultural, or thematic studies” (p. 130). Quantitatively content analyses have been used to count the presence and images of cultural groups or cultural phenomena found within children’s literature (Galda et al., 2000). Qualitatively content analysis is used to frame texts in a social, political, or cultural context (Short, 1995). My critical content analysis of Mixed Me and I am Mixed uses both quantitative and qualitative methods to provide a full understanding of the texts.

After reading the two texts I categorized specific patterns that I saw throughout the books in the text and from the images. Krippendorff (2004) states, “Therefore, the text is not limited to words but can also include any object, such as pictures and other images that hold meaning for someone or is produced to have meaning” (p. 19). To further explain why this is a fitting method for analyzing children’s books, Braden et al. (2016) state, “Thus, the critical content analysis is an appropriate method to utilize while investigating cultural artifacts such as books and pictures as is allows the researcher to look at both text and pictures” (p. 61). This methodology and the SIT framework allowed me to examine the texts to identify what cultural scripts multiracial children’s books use to help multiracial children shape their identity.

Theoretical Framework

In Social identity theory (SIT), a person’s social identity is the knowledge that she, he, or they belong to a social group or social category (Abrams & Hogg, 1988). Memberships to certain groups help us construct our identities.

RQ1: What key themes/messages are found in the multiracial children’s books, Mixed Me and I am Mixed?

RQ2: How can the themes/messages Found in the multiracial children’s books, Mixed Me and I am Mixed be used as tools by mothers to shape multiracial children’s identities?

Results/Findings

Mixed Me

Mixed Me follows the life of a multiracial child named Mike whose nickname is Mixed-up Mike. Through the illustrations, it is shown that Mike has curly deep auburn hair, two different colored eyes (one greenish-blue and one hazel), and a lighter complexion. Mike’s father is darker-skinned (phenotypically black) and his mother is tan with orange hair (phenotypically ambiguous). Mike navigates how he is perceived at school throughout the story.

I am Mixed follows the lives of multiracial twins Nia and Jay. The illustrations show that Nia has dark brown curls, dark eyes, and a darker complexion than her twin Jay who has sandy blonde curls, dark eyes, and a lighter complexion. These two being multiracial twins represent how different multiracial twins can be.

I am Mixed has a feature on the last few pages of the book where the child can draw a picture of themselves, write their name, and fill out an “about me” section; listing their favorite food, song, where they were born, what language their family speaks, where their mom is from, where their dad is from, and why that makes them special. This book is certainly suited to help multiracial children shape their identity.

Both Mixed Me and I am Mixed depicted messages through the text and illustrations that catered toward multiracial children and their families. The three main characters of the books are phenotypically illustrated to be of mixed race having skin, hair, and eyes that range from lighter to darker. No matter what shade the three main characters skin, hair, and eyes are they all have curly hair ranging from 3B to 4C curls. In both books, there is one darker skinned and one lighter-skinned parent illustrated. After reading the books I found three main themes throughout the books; hair, outside perception, and multiracial celebration.

Graph 1.1

Discussion

Hair

On the cover of Mixed Me half of the cover is a gorgeous deep auburn curly head of hair sitting on top of a multiracial boy with different colored eyes; one hazel and one green. Hair is mentioned three times throughout Mixed Me. On the first page hair is mentioned; “Hey now! They call me Mixed-up Mike. My hair is like WOW! Super-crazy-fresh-cool, man (Diggs, 2015). Hair being the opening topic is telling of the nature by which hair is an important trait of multiracial identity.

Perception

A unique experience that multiracial people live through is that the impact of other’s perceptions can affect how they racially identify. Doyle and Kao write, “All Americans are allowed to identify with the races that they feel best describes them” (p.406). Helms (1993) would describe this as personal identity. Multiracial people might be able to identify how they want, but how do others perceive them? For example, a multiracial person might personally identify as multiracial being of black and white ethnic background, but others might racially identify that person as black. This is why throughout both children’s books there are several references to outside perception. We can infer that the authors of these books understand the impact that outside perception has on multiracial children and how they view themselves. The theme of perception is mentioned six times throughout Mixed Me and one time throughout I am Mixed. Whether it is conscious or not, the impact that society can have on the self is significant (White 2000, 2010). And that is why the theme of perception is mentioned throughout Mixed Me and I am Mixed.

For example, in Mixed Me (2015) Diggs states, “Sometimes when we’re together people stare at whatever” (p. 9). The illustrations on this page show Mike and his family outside of the school bus stop. Mike is walking the dog skipping along with his eyes shut tight and a big smile on his face. In the background we see mom and dad holding hands behind him. The word choice of, “people stare at whatever.” In this sentence is indicative of Mike’s point of view as a child. He notices people looking at his family, but is not really quite sure why.

Next in Mixed Me, there is an illustration of Mike in school. There are two darker-skinned children scratching their heads and a blonde child with pigtails with her mouth shaped like the letter “O” They are all giving Mike the side eye while Mike happily holds up above his head a picture that he has drawn of his family. The text on this page reads, “Your mom and dad don’t match they say, and scratch their heads” (Mixed Me, 2015, p.11). This imagery along with the text demonstrates how when children are confronted with a family that looks differently from their own they may question this difference.

The next page follows the perception theme with an illustration of Mike in the middle of a big hug from his parents. We see Mike’s darker-skinned father and medium-skinned toned mother going in for an embrace of Mike. The text on this page of Mixed Me (2015) says, “See, my dad’s a deep brown and my mom’s rich cream and honey. Then people see me, and they look at us funny” (p.14).

Throughout the analysis of I am Mixed (2013) I only found the theme of perception mentioned one time. I believe that this is because I am Mixed is mostly geared toward multiracial celebration. Although I do believe that perception and multiracial celebration go hand-in-hand. This is because a part of multiracial celebration is not caring what others think. So, I do find it interesting that I only saw one occurence of the theme of perception throughout this book. On the pages with the example of the theme of perception the illustration shows Nia in school. Nia is sitting between a phenotypically Asian feminine child with straight dark brown hair and darker-skinned feminine child with 4c curly hair. The text on these pages of I am Mixed (2013) states, “When I go to school I get asked funny things like, your hair is bendy like curly wurly straws. It’s not straight like Sally’s or thick like Lenore’s” (pp. 7-8).

Multiracial Celebration/Positivity

Throughout the two books I saw a reoccurring theme of multiracial acceptance, not caring what others think, embracing ambiguity, and defining interracial families and multiracial children with positive metaphors. I call these themes throughout the books multiracial celebration/positivity.

In Jordan’s (2016) essay on children’s literature she states:

“I want to say to children that I love you and that you are-- and also precisely beautiful cause you are -- Black or female or poor or small or an only child or the son of parents divorced: you are beautiful and amazing: and when you love yourself truly then you will become like a swan release in the grace of natural and spontaneous purpose” (p. 18).

The theme of multiracial celebration was found the most throughout both books.

Conclusion | Moving Forward

Fox & Short (2003) state, “Stories do matter to children. They influence the ways in which children think about themselves and their place in the world as well as the ways in which they think about other cultural perspectives and people” (p.7). Since children’s books can influence how a child can perceive cultures outside of their own, a book that portrays a different culture can change influence how a child views that culture. Would a parent without multiracial children read a book like I am Mixed or Mixed Me to their child? Given the key themes that I found in, I am Mixed and Mixed Me I would argue that these books are made specifically for multiracial children and for the parents of multiracial children. The authors of these children’s books did not mention hair, perception, and multiracial celebration on accident. These are all things that most multiracial children will face throughout their lives in our culture. These books can be used as tools for mothers of multiracial children to not only help multiracial children shape and celebrate their own multiracial identities, but to also prepare multiracial children for how they may be perceived by others.

We as a society love to put people into boxes. “You’re a woman so you can’t speak up!” “You’re a man so you must not show emotion!” One could argue that having yet another category for multiracial children to identify could be problematic. Especially considering that there has been a public outcry in regards to gender for their to be no more gender/sex labeling. And because of the historical implications regarding how multiracial people legally can and personally can identify. Why should there be yet another identity category used to sort and define another group of people? I myself as a multiracial woman have struggled with which outcome is better. Anzaldua (2001) wrote about a new mestiza consciousness. A mestiza person is defined as: “A product of the transfer of the cultural and spiritual values of one group to another” (p. 94). Mestiza consciousness shares many correlations with the experience that multiracial Americans live through. Anzaldua (2001) wrote, “The new mestiza copes by developing a tolerance for contradictions, a tolerance for ambiguity” (p. 95).

When I was growing up in the late 90s and early 2000s children’s books like Mixed Me & I am Mixed did not exist. As a child my mother was not able to use these books as tools to help me shape my racial identity. But, my mother was still able to achieve similar outcomes without these books because, with or without them as a mother to a mutiracial child my mother wanted me to know that I am all things and that that is okay; similar to the theme of multiracial celebration. When children at my predominantly white school made fun of my hair she celebrated my curls. And when people would stare at us or not understand that she as a White woman was my mother, she made sure that the perception of others was never something that brought us down. My mother used the same themes that were found in the analysis of these books to help me self-identify however I felt fit.

As a multiracial person I understand the importance of legitimate identification, as in having a category, having a language to express oneself; but, being multiracial also helps me understand the beauty and the power in ambiguity. It is my hope that as we grow as a culture we have room for people who exist in ambiguity. And until then those who mother multiracial children can use these books as tools to help their children understand being multiracial in today’s culture.

Because I, a mestiza,

Continually walk out of one culture

And into another,

Because I am in all cultures at the same time,

Alma entre dos mundos, tres, cuatro,

Me zumba la cabeza con lo contradictorio.

Estoy norteada por todas las voces que me hablan

simultáneamente

-From Gloria Anzaldua, ‘La Conciencia de la Mestiza: Towards a New Consciousness (2001, p. 93)

References

Abrams, D., & Hogg, M. A. (1988). Comments on the motivational status of self‐esteem in social identity and intergroup discrimination. European journal of social psychology, 18(4), 317-334.

Anzaldua, G. (2001). La conciencia de la mestiza: Towards a new consciousness. In Feminism and 'Race', 93-107. NY: Oxford University Press.

Beach, R., Enciso, P., Harste, J., Jenkins, C., Raina, S. A., Rogers, R., & Yenika-Agbaw, V. (2009). Exploring the “critical” in critical content analysis of children’s literature. In 58th yearbook of the National Reading Conference (pp. 129-143)

Beauvais, G., Jones, S., & Webster, J. C. (2013). I Am Mixed. Stranger Kids.

Bennett, C. E. (1995). The Black Population in the United States: March 1994 and 1993. Current Population Report.

Billig, M., & Tajfel, H. (1973). Social categorization and similarity in intergroup behaviour. European journal of social psychology, 3(1), 27-52.

Braden, E. G., & Rodriguez, S. C. (2016). Beyond Mirrors and Windows: A Critical Content Analysis of Latinx Children's Books. Journal of Language and Literacy Education, 12(2), 56-83.

Brubaker, R. (2004). Ethnicity without groups. Harvard University Press. Print.

Brunsma, David et. al (2009). Racing to theory or retheorizing race? Understanding the struggle to build a multiracial identity theory. Journal of Social Issues, 65 (1), 13-34.

Burgess, S. R., Hecht, S. A., & Lonigan, C. J. (2002). Relations of the home literacy environment (HLE) to the development of reading‐related abilities: A one‐year longitudinal study. Reading Research Quarterly, 37(4), 408-426.

Butler-Sweet, C. (2011). ‘Race isn't what defines me’: Exploring identity choices in transracial, biracial, and monoracial families. Social Identities: Journal For The Study Of

Race, Nation And Culture, 17(6), 747-769. doi:10.1080/13504630.2011.606672

Clay, M. M. (1977). Reading: The patterning of complex behavior, hxeter. INH: Heinemann.

Compton-Lilly, C. (2003). Reading families: The literate lives of urban children (Vol. 23). Teachers College Press.

Diggs, T., & Evans, S. W. (2015). Mixed Me! New York: Feiwel & Friends.

Doyle, J., & Kao, G. (2007). Are racial identities of multiracials stable? Changing self-identification among single and multiple race individuals. Social Psychology Quarterly, 70(4), 405-423.

Farley, R. (2002). Racial identities in 2000: The response to the multiple-race response option.

The new race question: How the census counts multiracial individuals, 33-61.

Fox, D. L., & Short, K. G. (2003). Stories Matter: The Complexity of Cultural Authenticity in Children's Literature. National Council of Teachers of English.

Galda, L., Ash, G. E., & Cullinan, B. E. (2000). Children’s literature. Teoksessa ML Kamil, PB

Mosenthal, PD Pearson & R. Barr. Handbook of reading research.

Golub, M. (2005). Plessy as “passing”: Judicial responses to ambiguously raced bodies in Plessy v. Ferguson. Law & Society Review, 39(3), 563-600.

Greenhough, P., & Hughes, M. (1999). Encouraging conversing: Trying to change what parents do when their children read with them. Reading, 33(3), 98-105.

Gumbs, A. P. (2016). M/other Ourselves: A black queer feminist genealogy for radical mothering. In Revolutionary mothering: Love on the front lines (pp. 19–31). Ontario, CA: Between the Lines.

Harris, H. (2013). A National Survey of School Counselors' Perceptions of Multiracial Students.

Professional School Counseling, 17(1), 1-19. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.lib.usf.edu/stable/profschocoun.17.1.1

Helms, J. E. (1993). I also Said," White Racial Identity Influences White Researchers". The Counseling Psychologist, 21(2), 240-243.

Hogg, M. A., Terry, D. J., & White, K. M. (1995). A tale of two theories: A critical comparison of identity theory with social identity theory. Social psychology quarterly, 255-269.

Jordan, J. (2016). The Creative Spirit. In Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines (pp. 11–18). Ontario, CA: Between the Lines.

Kalish, S. (1995). Multiracial births increase as US ponders racial definitions. Population Today: News, Numbers, and Analysis, 23(4), 1-2.

Khanna, N. (2010). "IF YOU'RE HALF BLACK, YOU'RE JUST BLACK": Reflected Appraisals and the Persistence of the One-Drop Rule. The Sociological Quarterly, 51(1), 96-121. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.lib.usf.edu/stable/20697932

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Reliability in content analysis. Human communication research, 30(3), 411-431

Lewis, R., & Ford-Robertson, J. (2010). Understanding the Occurrence of Interracial Marriage in the United States Through Differential Assimilation. Journal of Black Studies, 41(2), 405-420. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.lib.usf.edu/stable/25780784

Lorde, A. (1984). Sister Outsider: Essays and speeches. Trumansburg, NY: Crossing Press.

Masuoka, N. (2011). The “Multiracial” option: Social group identity and changing patterns of racial categorization. American politics research, 39(1), 176-204.

Masuoka, N. (2017). Multiracial identity and racial politics in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press.

Omi, M., & Winant, H. (1994). Racial formation in the united states: From the 1960s to the 1990s (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Patterson, A. (2013). Chapter 6: Can One Ever Be Wholly Whole? Fostering Biracial Identity Founded in Spirit. Counterpoints, 454, 144-166. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.lib.usf.edu/stable/42982250

Perkins, R. (2014). Life in duality: biracial identity development. Race, Gender, & Class, 21(½), 211-219. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.lib.usf.edu/stable/43496970

Perlmann, J., & Waters, M. C. (2005). The new race question: How the census counts multiracial individuals. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Poston, Carlos (2011). The biracial identity development model: a needed addition. Journal of Counseling and Development. 69 (2),152-155. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1990.tb01477.x

Rockquemore, K., & Brunsma, D. (2002). Socially Embedded Identities: Theories, Typologies, and Processes of Racial Identity among Black/White Biracials. The Sociological Quarterly, 43(3), 335-356. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.lib.usf.edu/stable/4121531

Root, M. P. (1990). Resolving" other" status: Identity development of biracial individuals. Women & Therapy, 9(1-2), 185-205.

Roth, W. (2005). The end of the one-drop rule? Labeling of multiracial children in black intermarriages. Sociological Forum, 20(1), 35-67. doi:10.1007/s11206-005-1897-0

Seaton, E., Sellers, R., & Scottham, K. (2006). The Status Model of Racial Identity Development in African American Adolescents: Evidence of Structure, Trajectories, and Well-Being. Child Development, 77(5), 1416-1426. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.lib.usf.edu/stable/3878442

Short, K. G. (1995). Research & Professional Resources in Children's Literature: Piecing a Patchwork Quilt. Order Department, International Reading Association, 800 Barksdale Rd., PO Box 8139, Newark, DE.

Smedley, Audrey (2005). Race as biology is fiction, racism as a social problem is real: anthropological and historical perspectives on the social construction of race. American Psychologist, 60 (1), 16-25.

Smith, F. (1976). Learning to read by reading. Language Arts, 53(3), 297-322.

Snow, C. E., Burns, M. S., & Griffin, P. (2003). Preventing reading difficulties in young children. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Winn, N. N., & Priest, R. (1993). Counseling biracial children: a forgotten component of multicultural counseling. Family Therapy: The Journal of the California Graduate School of Family Psychology, 20(1)

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.