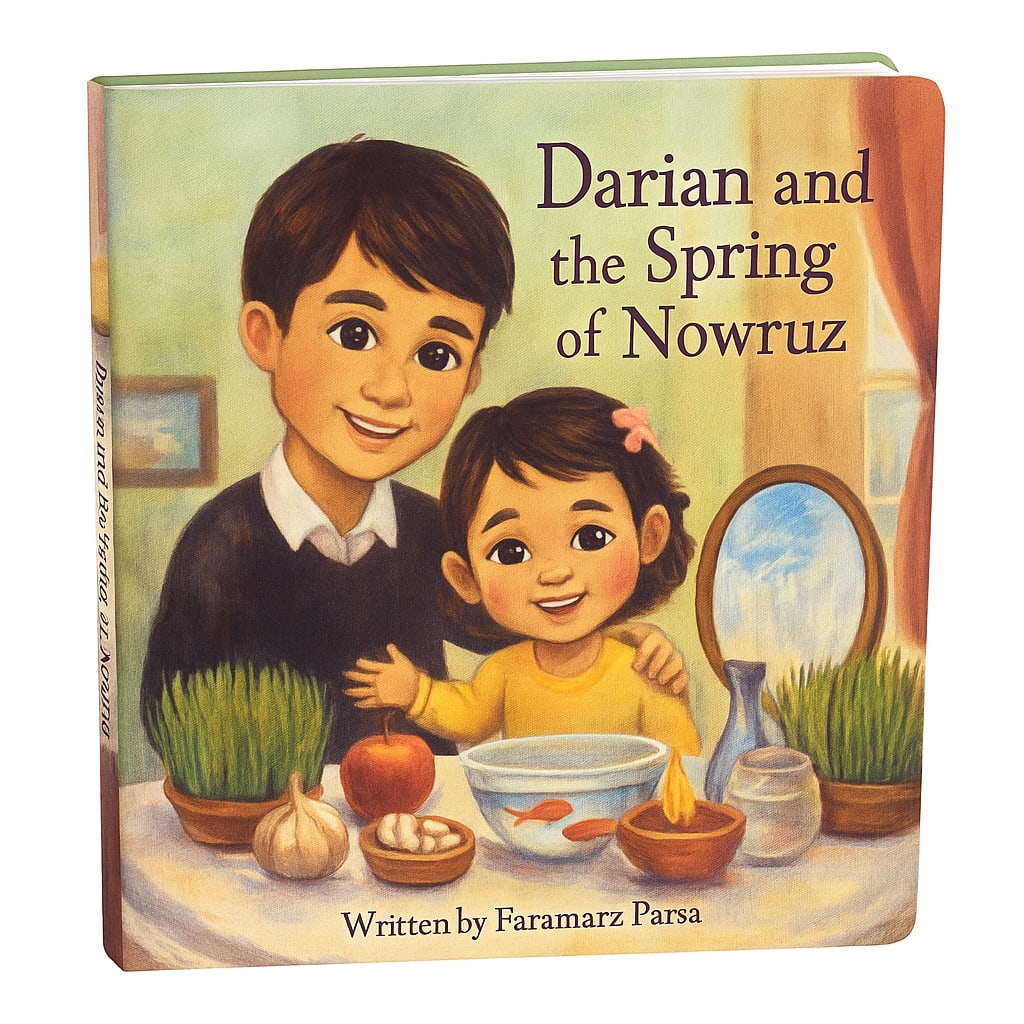

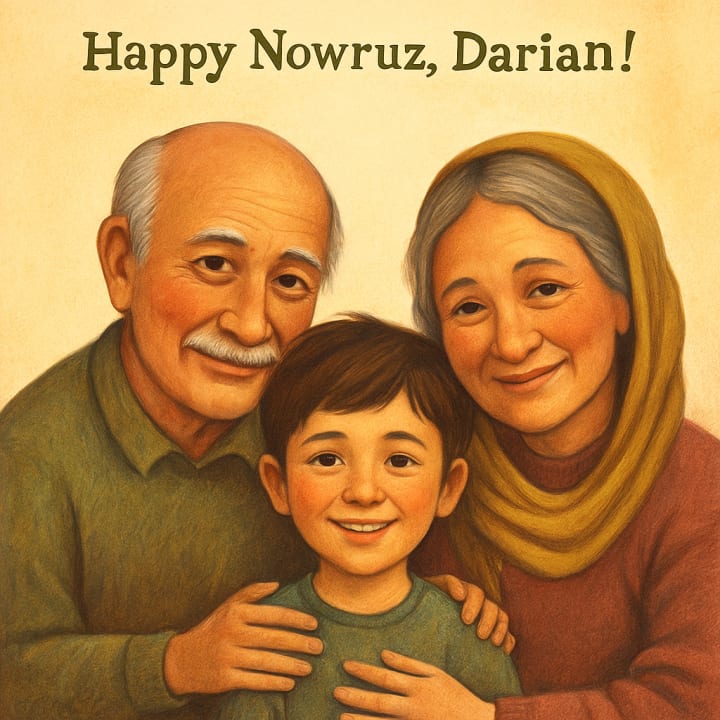

Darian and the Spring of Nowruz

A joyful Persian New Year story about family, kindness, and new beginnings

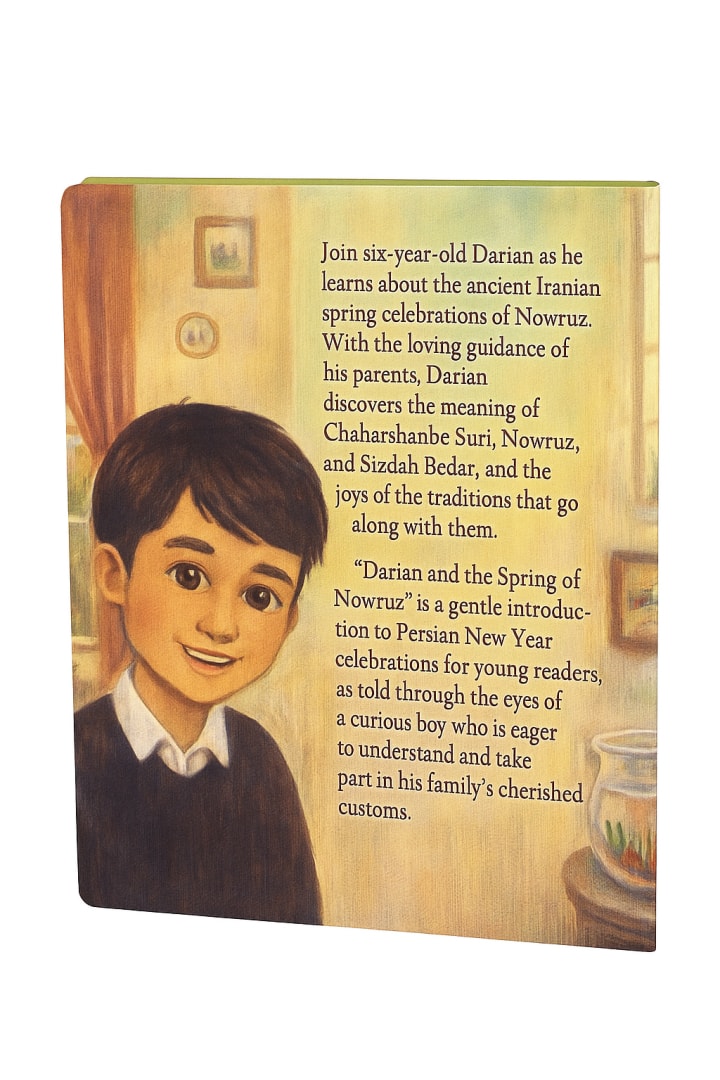

Join six-year-old Darian on a heartwarming journey through the vibrant celebrations of Nowruz, the Persian New Year.

With the loving guidance of his parents, Darian learns about the joy and meaning behind Chaharshanbe Suri, Nowruz, and Sizdah Bedar — three beautiful traditions that mark the arrival of spring and new beginnings.

Through colorful storytelling and tender family moments, Darian and the Spring of Nowruz introduces young readers to the sights, sounds, and spirit of Iranian culture.

Perfect for children curious about world traditions — or families wishing to share their own heritage — this gentle tale celebrates love, renewal, and the happiness that comes from understanding one another.

🌸 Inspired by Persian traditions and written with love by Faramarz Parsa.

📚 You can find Darian and the Spring of Nowruz on Amazon — a joyful story for every family that celebrates kindness, culture, and love.

For Adriana and Darian — with love from Bozorg

My name is Darian. I’m six years old, and I was born in San Diego.

My mom and dad are from Iran, and every spring we celebrate something very special called Nowruz — the Persian New Year

Most of my friends don’t know about it, so this year I decided to tell them everything I learned.

One night, just before Nowruz, Mom said:

“Tonight is Chaharshanbe Suri, the last Wednesday of the year. In Iran, people jump over little fires to say goodbye to the old year.”

I asked, “Why do they jump, Mom? Isn’t that scary?”

She smiled and said, “They say: Zardi-ye man az to, sorkhi-ye to az man!

It means, ‘Take away my sadness, and give me your warmth and joy.’”

Dad built three small fires in our backyard.

He held my hand, and together we jumped over them. I felt brave — like a flying bird!

Then Mom told me another story:

“In Iran, kids also do something called ghashogh-zani — spoon knocking. They cover their faces with scarves, hold a bowl and a spoon, and knock on doors. People open the door and put nuts and candy in their bowls!”

I laughed. “So… it’s like Persian Halloween!”

Dad laughed too. “Yes, but instead of candy, they share kindness and wishes for a happy new year.”

I thought that sounded even better than Halloween.

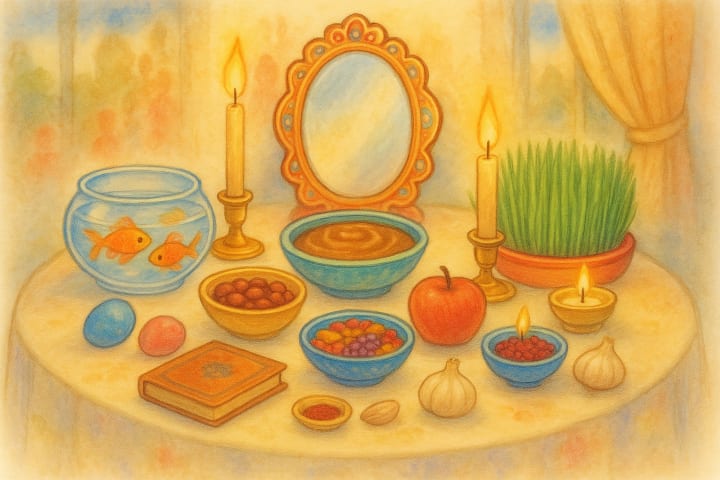

A few days later, Mom set a beautiful table called the Haft-Seen — “The Seven S’s.”

Each thing on the table started with the Persian letter S.

I looked closely and asked, “Mom, what do they mean?”

She said:

Sabzeh – green sprouts for new life.

Samanu – sweet pudding for blessings.

Seer – garlic for protection.

Seeb – apple for health.

Senjed – dried fruit for love.

Serkeh – vinegar for patience.

Somaq – spice for the sunrise and strength.

There was also a mirror, symbol of a bright heart, and a bowl with two goldfish swimming in clear water.

I named them Niki and Roshan — “Goodness” and “Light.”

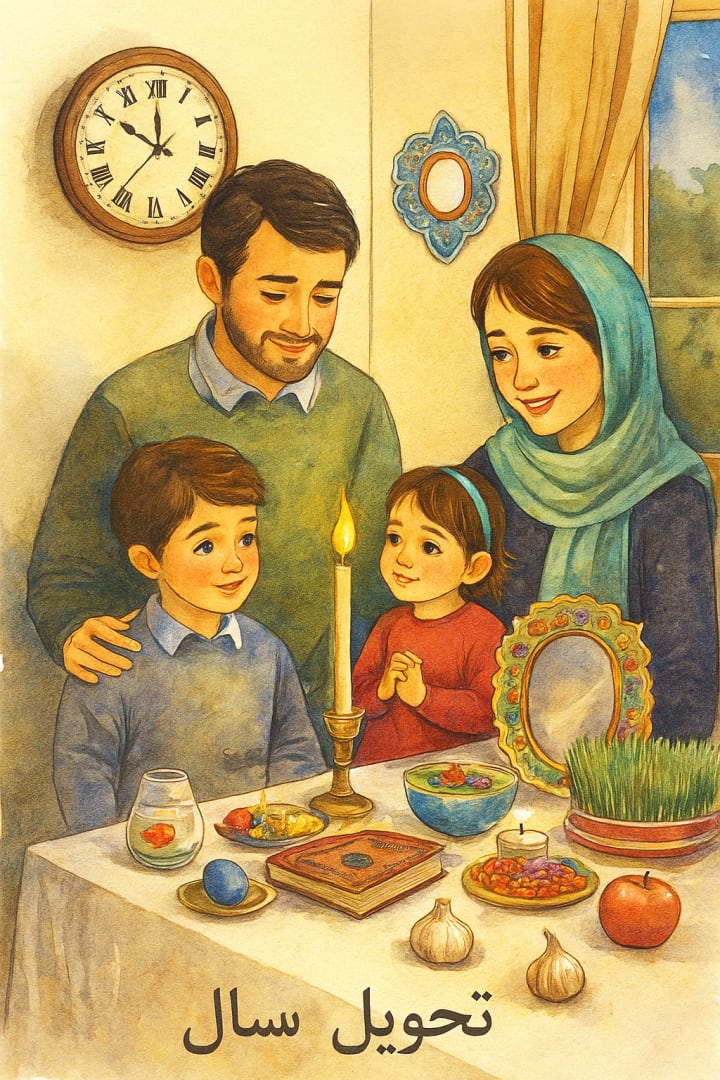

Nowruz starts at the precise moment of the vernal equinox, that’s when the sun crosses the equator. This moment does not occur on the same day or time every year.

When the clock strikes, we all say “Happy Nowruz!”

I kissed my little sister Adriana, who is only two years old.

She laughed and tried to say “Happy New Year!” but it came out funny.

Then we all hugged, and Dad gave me a small red envelope — my Eydi, or new year’s gift.

Mom said softly, “Nowruz is about love, family, and new beginnings. We celebrate to remind ourselves that life can always start fresh.”

I smiled and whispered,

“I hope everyone in the world has a little spring in their heart.”

In Iran, people visit their grandparents and relatives for 13 days to say “Eid Mobarak” and celebrate the new year.

Since our family lives far away, we called them on video.

Grandma waved from Tehran and said, “Happy Nowruz, my dear Darian!”

I shouted, “Happy Nowruz, Maman Joon! I planted my Sabzeh!”

She laughed and said, “That’s my good boy!”

On the 13th day, we celebrate outdoors. My family and I went to a park near the lake.

It was full of families, laughter, music, and the smell of kabob.

Mom said, “This is Sizdah Bedar, the day we go outdoors to say goodbye to the holidays.”

I asked, “Why do we throw the sabzeh into the water?”

Dad said, “Because we give back to nature what we borrowed — life and hope. Some people even tie the greens together and make a wish.”

I saw young girls tying their Sabzeh and whispering with closed eyes.

So I closed my eyes too and said, “I wish every child in the world could be happy and see their grandparents soon.”

Then I placed my Sabzeh in the water.

It floated away, shining under the sun like it was carrying my wish to the sea.

Mom said, “Now your wish will travel with the wind, little one.”

That night, when I went to sleep, I could still smell spring — the scent of fire, flowers, and my sister’s new-year kiss.

Chaharshanbe Suri

The Festival of Fire and Purity — the last sunset of the year’s final Wednesday.

Its roots go back to Zoroastrian rituals, symbolizing the passage from darkness to light, and liberation from evil and illness.

Fire in this night represents the sun, life, and renewal.

People leap over the flames and chant: “Take away my paleness, give me your redness,” meaning, take my sorrow and pain, and give me your warmth and vitality.

In ancient times, this night was also marked by listening for omens, knocking on doors in disguise (“spoon-banging”), cooking ash reshteh (a thick herb noodle soup) or a mixture of roasted nuts called ajil-e moshkel-gosha (“problem-solving mix”), and gathering with family.

At the heart of this ritual lies the wish to be cleansed of all that has passed and to prepare for a new birth.

Nowruz and the New Year

Nowruz means “New Day” — the dawn of spring and the rebirth of the earth.

Its mythic origin traces back to the reign of King Jamshid in the Shahnameh, yet in essence it symbolizes cosmic order and the renewal of life’s cycle.

The Haft-Seen table — that mystical arrangement — holds symbols of vitality and human hopes:

Sabzeh (sprouts — growth), Senjed (oleaster — love and wisdom), Seeb (apple — beauty and health), Seer (garlic — protection from evil), Somāgh (sumac — patience), Serkeh (vinegar — acceptance of life’s bitterness), and Samanu (sweet pudding — strength and abundance).

Other symbolic items that are typically used to accompany the Haft-Seen table are a mirror, a book of wisdom, goldfish, colored eggs and traditional Persian confections are also included.

At the moment of the year’s turning, families sit together, recite prayers or blessings, and share a kiss — a token of love and renewal.

Sizdah Bedar

The thirteenth day of Farvardin marks the custom of leaving home to cast away misfortune and dwell in nature.

Yet its deeper meaning is the return of humankind to the embrace of the earth — to its origins.

In ancient Persian mythology, the thirteenth day was a blessed day dedicated to Tishtrya, the god of rain.

People went outdoors to give thanks and seek continued fertility of the land.

Tying blades of Sabzeh together symbolized love, wishes, and hope; throwing them into running water meant releasing sorrow and the old year’s residue.

In truth, Sizdah Bedar is the festival of farewell to Nowruz and greeting the season of work, growth, and new life.

About the Creator

Ebrahim Parsa

⸻

Faramarz (Ebrahim) Parsa writes stories for children and adults — tales born from silence, memory, and the light of imagination inspired by Persian roots.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.