Thoughts on Series expansions and what I call matrix parse-able algebra or the better known Linear algebra

Simple proof of polynomial derivative and some cool stuff after that's worth thinking about

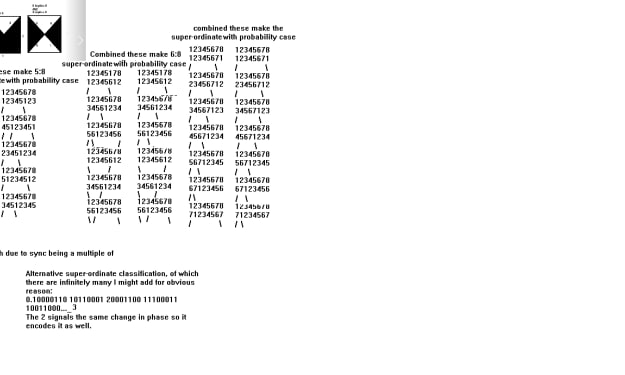

Proof of polynomial derivative using binomial expansion which is useful because it means if we have a polynomial series expansion for any function then we can find the derivatives by taking the derivative of the terms which are all polynomial and if we can produce a partial sum formula where the output of the series expansion is rational in nature for every input or it is the case that

we know the function that our next series expansion converges to then we can give the short hand as well, but it's doesn't really matter if you just want to build a calculator because they use the series expansions to determine the outputs of the function the expansion converges to anyway so it's not really relevant:

Secant formula for derivatives applied to polynomial derivatives which has a visual I'll show after:

limit delta(x)->0 of (f(x+delta(x))-f(x))/(delta(x)) = (dy/dx)

limit delta(x)->0 of (x+delta(x))^n-x^n)/(delta(x)) = (dy/dx)(x^n)

limit delta(x)->0 of (x^n...n*x^(n-1)*delta(x)^(n-1)+delta(x)^n-x^n)/(delta(x)) = (dy/dx)(x^n)

limit delta(x)->0 of (n*x^(n-1)+...delta(x)^(n-1)) = (dy/dx)(x^n)

If you notice I eliminated a bunch of terms in the ... it's because those all have delta(x) as a multiple and the first term actually lost its delta(x) so it's good.

You just have to think about the actual expansion

it is n*x^(n-1) for the (n-1) term because it's x multiplied

by itself all but one time in every single way and that means taking

those bracketed values and choosing x for each but one and doing that in all possible permutations which gives n*x^(n-1)

(dy/dx)(x^n) = n*x^(n-1)

Next you can note that given a polynomial expansion with coefficient we have

(dy/dx) (sum from m=0 to n of (a_m*x^m))

and if we were to plug that into our secant formula for the derivative we'd find that the first term a_nx^n is simply the (dy/dx)x^n * (limit as delta(x)->0 a_n)

nx^(n-1)*a_n because the a_n limit has no x term to deal with so

we treat as a simple multiple of the other secant to tangent derivative

Next we can finally note that

(dy/dx) (sum from m=0 to n of (a_m*x^m))

= (0*a_1x^1)+(1*a_2*x^2)...+(a_(n-1)*n*x^(n-1))

And if you're second guessing just remember that each of

the terms are subunits of that secant formula expansion

all of which have derivatives of that same initial polynomial

form and those have coefficients and the coefficients are just multiples since they haver no delta(x) and the exponents determine

the derivative values for each corresponding term and if you noticed I used the term a_1 first despite the zero multiple I did

so because in Linear algebra, which I call matrix parse-able algebra

your standard system of equations will be linear because matrix

algebra is designed well for parsing linear systems since other

systems present categorical issues upon attempting to enumerate

them as positions in the n-dimensional matricies which you can

confirm yourself by simply attempts to logically place things like

e^x or log(x) in terms of the array placement. As far as I know

there exists no dial for transitioning between these places in the arrays and so when we are dealing with non-linear systems

we are limited in terms of our ability to do mathematics or linear

algebra with those systems. It's less meaning to combine the rows

for example in many circumstances, and if you can't perform

a linear substitution then you don't have as much at your disposal. A matrix inverse for example might not really be meaningful, unless you can do something like a rotation on the matrix, which would be one way to think of an inverse, but that depends on how you graph works out. If you don't have the correct line of symmetry then the inverse isn't doing what you want so you might need to adapt for that, but I'm not even sure if or where that's possible it's just a thought of mine.

Now if we have a series polynomial expansion that converges to

lets say sin(x) or other functions then we can create linear systems that approximate non-linear systems in linear algebra or we can just take those functions and use them in calculus to proof derivations of functions that have not yet been incorporated into our vocabulary and if you have a linear system approximation that has an inverse then you can take that inverse and then you a method for producing partial sum formulas for those functions which could tell you something about the convergence of those functions and maybe you can map back to the shorthand notation you initially used and then we can take the derivative of something like sin(x) in a much simpler fashion than I just stated to find cos(x) and that is calculated using it's expansion which is necessary because splines do not produce those waveforms. You need polynomial approximation to produce them because the splines do not tend to those functions of x in the complex version circle because the splines are only subsets of terms in the expansion unless you're really clever and pointless and decide to make splines that are partial series expansions that get better and better and then you reevaluate your approximation after perform that task which is just completely pointless I'm just explaining why not to bother going down that route linguistically because I'm good at that and

series expansion is the same and less pointless, and easier to do because the splines need to satisfy certain criteria so even if they are partial expansions it's just more needless shit to do with a piecewise function that requires if then else statements to compute anyway, but parabolic waves, and cubic waves for example are things and you may want to use splines to produce those waveforms because they're distinct things of value in other areas.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.