The Discovery That Changed Medicine

The Invention of X-Rays by Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen in 1895

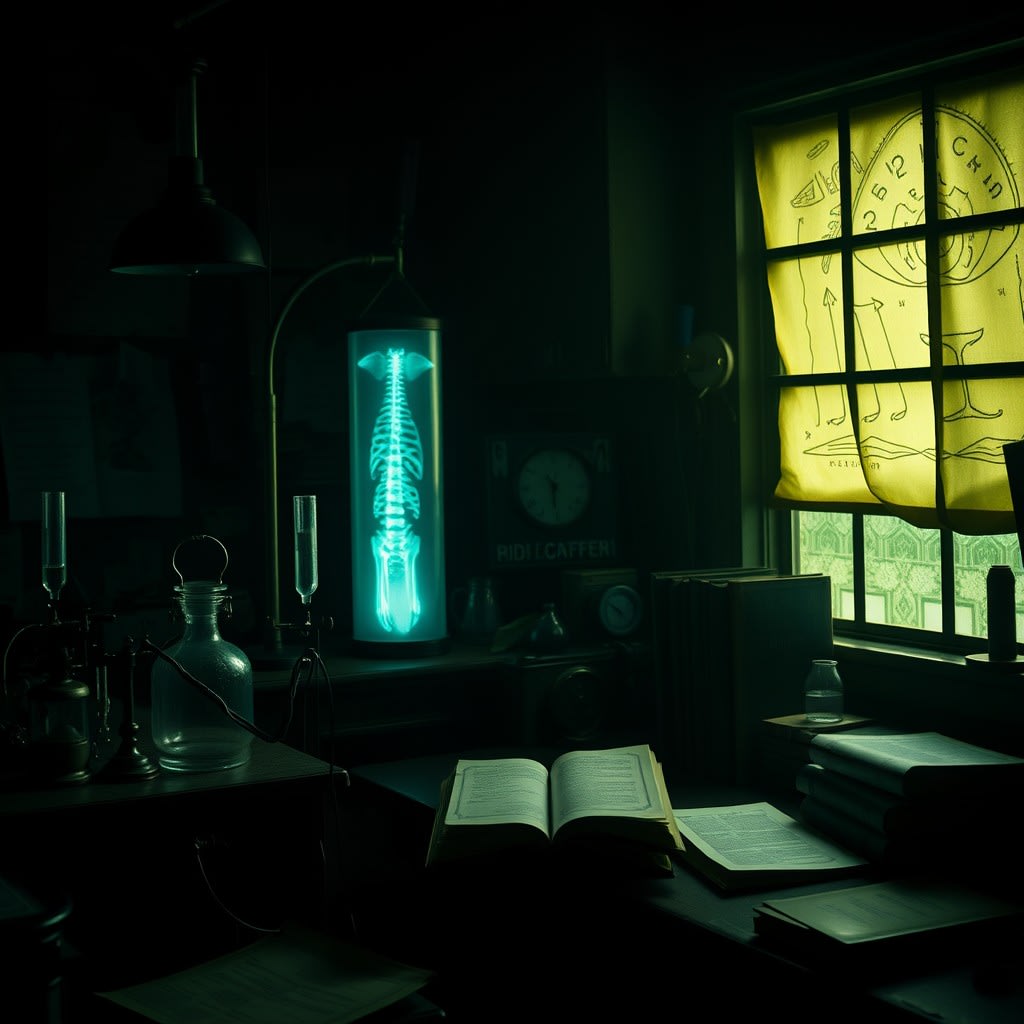

In the late 19th century, the world of physics was quietly simmering with potential. Electricity, magnetism, and invisible rays had become the subjects of endless curiosity among scientists. Laboratories were small, often dimly lit rooms filled with flickering tubes, coils, and wires. It was in one such laboratory in Würzburg, Germany, that Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, a modest and meticulous professor of physics, was about to change the world—not with a loud bang, but with a glow in the dark.

Röntgen was not known for flamboyant gestures or wild theories. In fact, he was considered somewhat reserved, even secretive, preferring to let his work speak for itself. But he had a mind that never settled for the surface of things. He sought the hidden layers of nature, the things unseen.

It was a cool evening in late October 1895 when Röntgen was working alone in his lab. He had been experimenting with cathode ray tubes—sealed glass tubes in which electric currents were passed through gases at low pressure. These devices were already known to produce strange behaviors. Scientists had discovered that these tubes emitted rays that could cause a screen coated with certain chemicals to glow. However, these rays did not travel far, and their properties were still largely a mystery.

On this particular night, Röntgen noticed something strange. He had wrapped a cathode ray tube—specifically, a Crookes tube—in black cardboard to block the visible light. Yet, when he turned it on, he noticed a faint glow on a fluorescent screen coated with barium platinocyanide that was lying across the room. The glow appeared even though the tube was completely covered.

Perplexed, Röntgen moved the screen around the room. The glow persisted whenever the tube was on, but only when the screen was in its line of sight. He quickly realized that some kind of invisible ray was coming from the tube and passing through the cardboard. These rays could not be cathode rays, which were known not to travel far through air, let alone solid materials.

Röntgen, intrigued, began a series of meticulous experiments. He placed various objects between the tube and the screen—books, wood, paper, metal—and noticed something astonishing: some objects allowed the mysterious rays to pass through, while others blocked them. Most surprisingly, when he held his hand in front of the screen, he saw the bones of his fingers silhouetted against the glow.

He was witnessing something no human had ever seen before—the inside of a living body without surgery.

For the next several weeks, Röntgen hardly left his lab. He ate little, slept sporadically, and told almost no one about his discovery. He worked with intensity, testing different materials to learn which were transparent to the new rays. He discovered that the denser the material, the more it blocked the rays. He took photographs using photographic plates—images of metal objects inside wooden cases, of weights inside sealed boxes, and famously, of his wife Bertha’s hand.

When Bertha saw the image—her skeletal hand adorned with the shadowy outline of her wedding ring—she recoiled in fear. "I have seen my death," she reportedly said. It was a sentiment that many would come to feel in the presence of this ghostly new technology.

On December 28, 1895, Röntgen submitted a paper to the Würzburg Physical-Medical Society titled “On a New Kind of Rays.” He called them X-rays, with "X" standing for "unknown." The paper was concise, only about nine pages long, but it caused an immediate sensation in the scientific community.

By early January 1896, newspapers across Europe and America were publishing stories about the new rays that could see through flesh and clothing. The public was fascinated—and sometimes horrified—by the implications. Some people feared that strangers might use X-rays to spy on them through walls or peek under their garments. Skeptics doubted the validity of the images entirely, calling them scientific tricks.

But scientists and physicians quickly understood the value of Röntgen’s discovery. Within months, X-ray machines were being used in hospitals to locate bullets and broken bones. What had once been purely speculative science became a practical medical tool almost overnight.

In a time before MRI, CT scans, or even antibiotics, the ability to look inside the body without cutting it open was revolutionary. Surgeons could now pinpoint problems more precisely, reducing the need for exploratory surgeries. Dentists could see cavities in teeth. Engineers used X-rays to check for flaws in materials. It was one of the rare moments in history when a scientific discovery leapt from the laboratory to the real world with breathtaking speed.

In 1901, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen was awarded the very first Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery. He accepted it with his typical humility, saying little and continuing his research quietly. He never patented his invention, believing that knowledge should be shared freely for the benefit of humanity.

Röntgen’s life was not marked by extravagance. He remained a professor, lived modestly, and continued to teach and conduct research. During World War I, he refused to use his fame to support nationalist causes. When he died in 1923, he left behind no heirs, few possessions, and no personal fortune. But he had transformed medicine, physics, and even art.

Today, X-rays are everywhere—from airports and dental offices to astrophysics and industrial engineering. They have enabled countless lives to be saved, diseases to be detected early, and mysteries to be explored from the human body to distant galaxies. The mysterious “X” in X-rays, once a placeholder for the unknown, has become a symbol of deep insight and discovery.

And it all began in a dim German laboratory, with a flicker of invisible light and the curiosity of a man who wasn’t afraid to ask what lies beneath.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.