The Clockmaker of Thought: The Story of Charles Babbage

Before computers were ever real, one man saw their future in cogs, gears, and dreams.

The Story:

Long before screens lit up our world… before processors ran billions of calculations in a second… before the words "digital" or "software" even existed… there was a man who imagined it all.

His name was Charles Babbage, and in the 19th century, while steam engines powered factories and horse-drawn carriages ruled the roads, he envisioned something different: a machine that could think.

The Mathematician’s Problem

Charles was born in London in 1791, into a time of tremendous industrial growth. The world was changing fast, and Charles, with a sharp mind and tireless curiosity, was determined to be part of it.

But he had a problem.

As a young mathematician at Cambridge, Babbage often used mathematical tables—books filled with endless rows of numbers used in engineering, astronomy, and navigation. These tables were handwritten by clerks, and full of errors. One misprinted digit could sink a ship or misguide a telescope. It frustrated Babbage deeply.

One day, after finding yet another error, he reportedly exclaimed

“I wish to God these calculations had been executed by steam!”

It sounded mad to many. But Charles wasn’t joking.

He would spend the next decades trying to make it real.

The Difference Engine

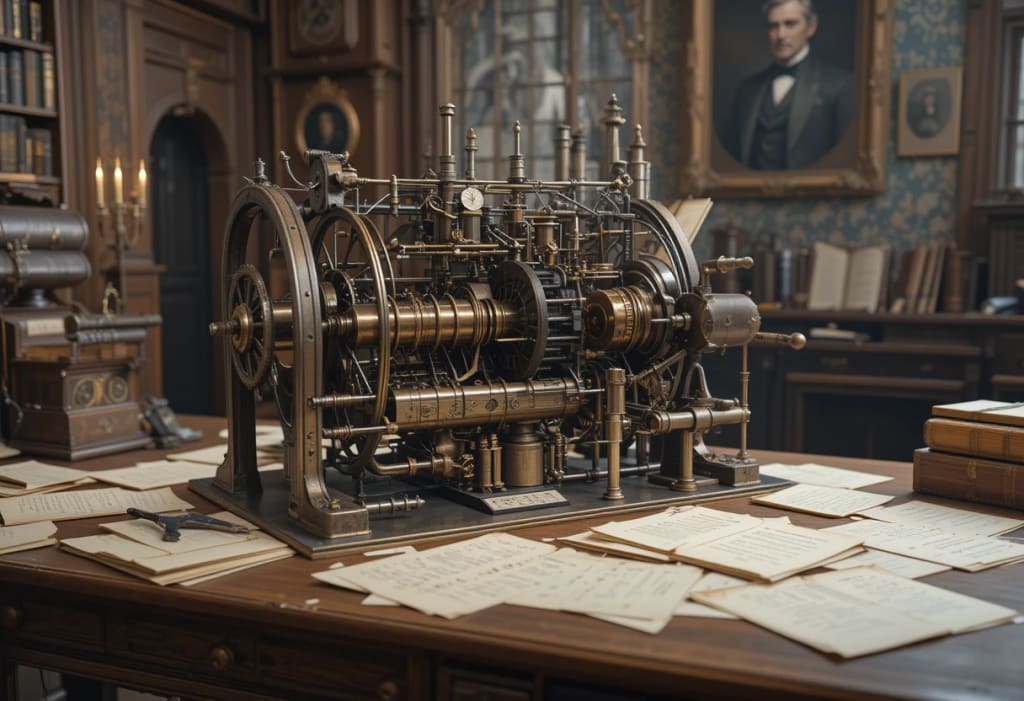

Charles Babbage set out to build a machine unlike anything the world had seen—a mechanical calculator driven by cranks, gears, and precision engineering. He called it the Difference Engine.

It was massive—an estimated 25,000 parts—and would have weighed over 15 tons if completed. Powered by turning a handle, the machine could calculate and print accurate mathematical tables automatically.

With government funding and public fascination, Babbage began building it. But this was no small project. The machine required engineering skills and manufacturing precision that barely existed at the time.

After years of design changes, political interference, rising costs, and disputes with his engineer, the project was abandoned.

Most would have given up.

But Babbage wasn’t most men.

The Analytical Engine: A Machine That Could Think

Out of the ashes of the Difference Engine rose a more ambitious idea—the Analytical Engine.

This machine would do more than just add and subtract. It would use punched cards, much like the ones used in weaving looms, to give it instructions. It would have memory, a central processing unit, and a way to output results.

In essence, it was the first blueprint for a modern computer—a hundred years before anyone could build one.

Babbage wrote extensively about its design, but the machine was never built in his lifetime. It was too far ahead of its time.

But not everyone overlooked his genius.

Ada Lovelace: The First Programmer

One of Babbage’s closest collaborators was Ada Lovelace, daughter of poet Lord Byron. Fascinated by the Analytical Engine, she translated an Italian paper about it and added her own notes—which turned out to be three times longer than the original text.

In those notes, Ada described how the machine could do more than math—it could potentially compose music or manipulate symbols. She even wrote the first algorithm meant to be processed by the machine, making her the world’s first computer programmer.

Ada saw what the world didn’t: that Babbage’s machine wasn’t just mechanical—it was conceptual.

Legacy in Gears and Ideas

Charles Babbage died in 1871, frustrated and misunderstood. He had spent his life chasing a dream few could understand. None of his great engines were completed while he lived.

But the ideas behind them endured.

In the 20th century, as electronic computers were finally developed, Babbage’s work was rediscovered and recognized. In 1991, London’s Science Museum built a working version of the Difference Engine No. 2, using his exact designs—and it worked flawlessly.

His dream had not failed. It had simply arrived too early.

The Clockmaker of Thought

Charles Babbage was many things—a mathematician, philosopher, inventor, and dreamer. But more than anything, he was a man who saw the future inside the machines of his present.

He believed that logic could be mechanical, that thinking could be translated into turning gears and levers, and that a machine could do more than obey—it could process, understand, and assist.

Today, every computer, every phone, every algorithm owes a debt to the man who once wished his calculations could be executed by steam.

He may not have built the first computer, but he built the idea of one.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.