Journey Through the Cell Membrane: From Lipid Layers to Unit Membrane

How Scientists Unveiled the Hidden Structure of the Cell Membrane – A Timeline of Models from Overton to Robertson

What Is the Cell Membrane? | An Easy Guide for Medical Students

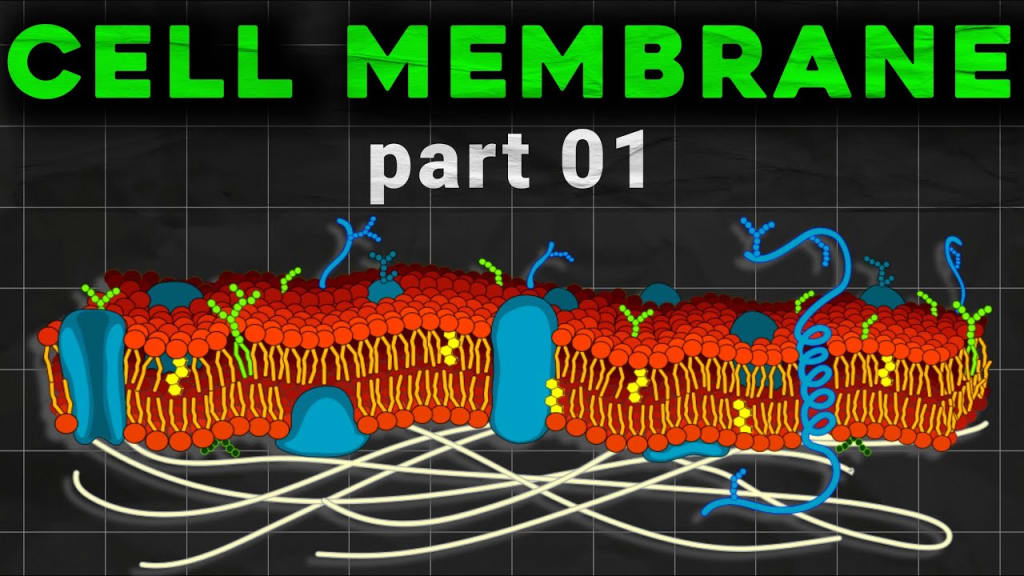

Cells are the basic building blocks of all living organisms, and understanding their structure is key to mastering biology. In this article, we’ll focus on one of the most important yet often misunderstood components of the cell — the cell membrane.

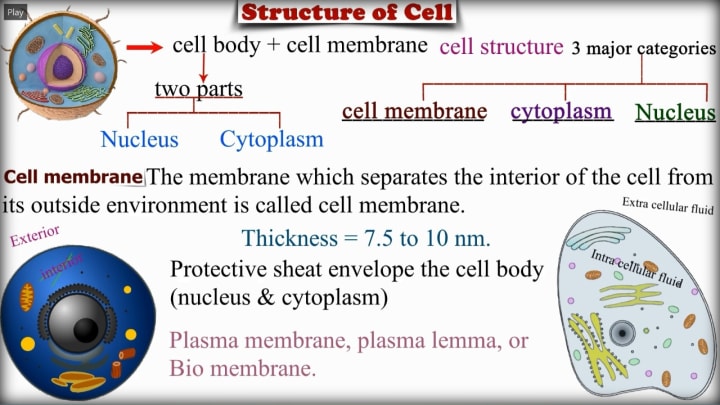

Overview of Cell Structure: Before diving into the membrane, let’s take a quick look at the overall structure of a cell. A typical cell has three major components:

Nucleus – the command center

Cytoplasm – the working fluid of the cell

Cell Membrane – the protective outer shell

In this article, we’re going to zoom in on the cell membrane, its structure, functions, and significance in maintaining life at the cellular level.

What Is the Cell Membrane?

The cell membrane, also known as the plasma membrane, plasma lemma, or bio membrane, is a thin layer that surrounds the entire cell. It acts like a gatekeeper, separating the internal environment (intracellular fluid) from the external environment (extracellular fluid).

Composition & Structure:

Thickness: The membrane is incredibly thin — only about 7.5 to 10 nanometers.

Protective Function: It serves as a protective sheath that wraps around both the nucleus and the cytoplasm.

Semi-permeable Nature: It allows certain substances to pass through while blocking others, maintaining a balance of nutrients and waste inside and outside the cell.

Historical Discoveries About Cell Membrane Structure

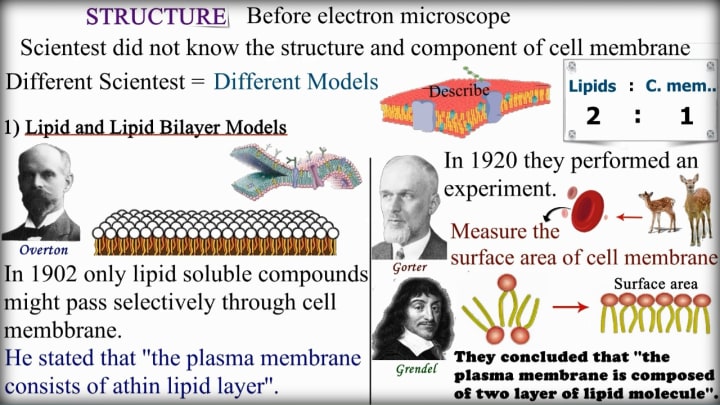

Before the Electron Microscope: Before advanced tools like the electron microscope became available, scientists had no clear idea about the structure or components of the cell membrane. They couldn't see microscopic details, so they had to rely on indirect experiments and logical deductions.

As a result, different scientists proposed different models of what the cell membrane might look like and how it functions.

1.Lipid and Lipid Bilayer Models:

The cell membrane is made up of lipids — specifically, a lipid bilayer.

Overton (1902): One of the first scientists to propose something meaningful was Overton in 1902. His experiments showed that only lipid-soluble substances (those that can dissolve in fat) could easily pass through the cell membrane.

This led him to a major insight: “The plasma membrane consists of a thin lipid layer.”

In simpler words, he believed that the outer boundary of the cell (the plasma membrane) is mostly made of fat (lipids). This was a big step forward in understanding cell structure.

Key Point: If something is lipid-soluble, it can pass through. If not, it probably can’t. That’s selective permeability — a key feature of membranes!

Gorter and Grendel (1920):Nearly two decades later, in 1920, Gorter and Grendel took Overton’s idea even further with a very smart experiment.

What did they do?

They extracted red blood cells from animals.

Then they measured the surface area of the cell membrane that came from those cells.

They compared the surface area of the lipids they extracted with the area of the cells themselves.

Result: The surface area of the lipids was twice the surface area of the cells.

Conclusion: The cell membrane isn’t made of just one layer of lipids…

It’s actually made of two layers — a lipid bilayer.

This was a groundbreaking discovery!

“The plasma membrane is composed of two layers of lipid molecules.”

This ratio is also illustrated in the image: Lipids : Cell Membrane = 2 : 1

This ratio directly supported the idea of a double layer.

Why This Matters:

Understanding the lipid bilayer was the foundation for everything that came after in cell biology. Once scientists knew that the membrane was made up of two layers of lipids, they could start exploring:

How proteins fit into the membrane

How substances move in and out of the cell

Why the membrane behaves like a flexible barrier

This slide captures the beginning of our understanding of the membrane’s structure — and it all started with logical thinking and careful measurements!

Evolution of Cell Membrane Models (Part 2)

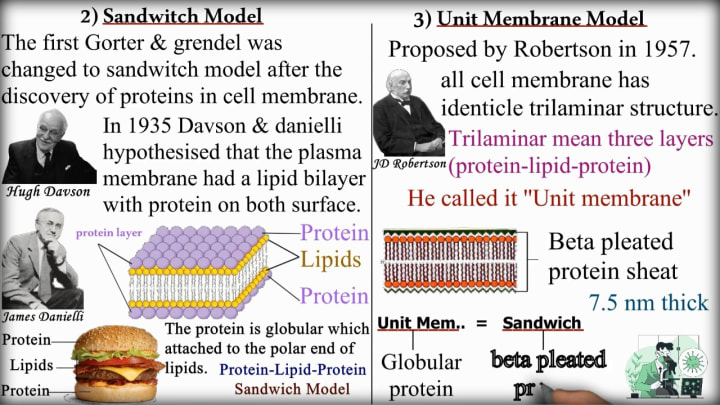

2) Sandwich Model (1935):

After Gorter and Grendel's lipid bilayer model, scientists discovered that proteins are also an important part of the cell membrane. This led to a new model:

Hugh Davson and James Danielli (1935): These two scientists hypothesized something new:

The plasma membrane has a lipid bilayer — but it is covered by a layer of protein on both sides.

Think of it like a sandwich:

The “bread” = proteins (on the outside and inside)

The “filling” = lipid bilayer (in the middle)

This is why it was called the Sandwich Model.

Key Idea:

Protein – Lipid – Protein

The protein layers are thought to be globular proteins, attached to the polar heads of the lipid molecules.

Why this model was proposed: At the time, scientists thought proteins were just sitting outside the lipid bilayer.

They had not yet realized that proteins could span through the membrane (which we learned later with the fluid mosaic model).

That’s why a literal burger sandwich image is shown — to visually help you understand how the components are stacked in this model.

3) Unit Membrane Model (1957):

JD Robertson (1957): In 1957, JD Robertson proposed the Unit Membrane Model. He was the first to observe cell membranes under an electron microscope. Here’s what he saw:

All cell membranes appeared to have a similar trilaminar (three-layered) structure.

So he came up with the "Unit Membrane" concept.

Trilaminar means:

Outer dark line (protein)

Middle light zone (lipid bilayer)

Inner dark line (protein)

So again, we have protein – lipid – protein, but now it was actually seen under the microscope, rather than just hypothesized.

Additional Points: These proteins were described as beta-pleated sheet proteins, a specific structural form of protein.

The thickness of the membrane was measured to be approximately 7.5 nm.

So essentially, the Unit Membrane Model = Improved Sandwich Model, backed with actual visual evidence from microscopy.

Summary of Both Models:

Sandwich Model (1935):

Proposed by Davson and Danielli.

Suggested the plasma membrane consists of a lipid bilayer sandwiched between two layers of proteins.

Compared to a sandwich: Protein–Lipid–Protein.

Protein layer is globular and attached to the polar ends of lipids.

Unit Membrane Model (1957):

Proposed by JD Robertson.

Described the membrane as a trilaminar structure: Protein–Lipid–Protein.

All biological membranes were thought to have the same basic structure.

Thickness of the unit membrane is approximately 7.5 nm.

Highlighted the beta-pleated protein sheet on either side of the lipid bilayer.

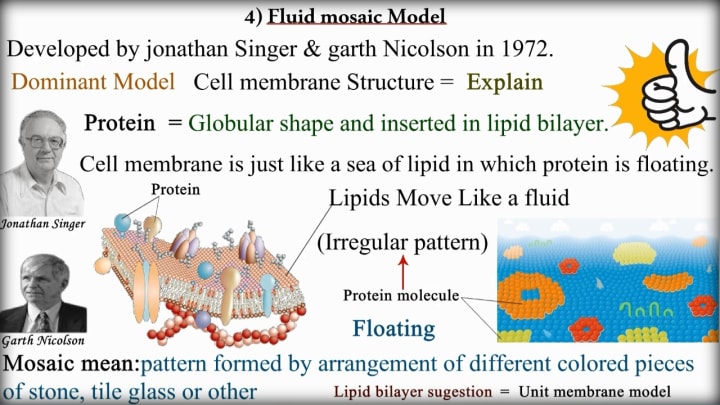

4) Fluid Mosaic Model (1972):

This model was developed by Jonathan Singer and Garth Nicolson in 1972, and it became the dominant and widely accepted model to explain the structure of the cell membrane.

Key Concepts: The cell membrane is not rigid or fixed; instead, it's dynamic—meaning its molecules can move and shift position.

According to this model, the membrane is made up of a lipid bilayer, in which proteins are embedded like floating objects.

Structure According to the Model: Lipids form the base structure, acting like a fluid "sea" in which other molecules can move.

Proteins are of globular shape and are inserted into the lipid bilayer, either partially or completely.

The movement of lipids and proteins within the membrane is not in a fixed pattern, which is why it's called "fluid".

Why "Mosaic"?

The term "mosaic" refers to a pattern made by assembling different pieces, like in tiles or stained glass. Similarly, the membrane is made of different molecules (proteins, lipids, carbs) that together form a complex, irregular pattern across the surface.

Key Characteristics: Proteins float in the lipid bilayer like icebergs in the sea.

Lipids and proteins can move sideways, giving the membrane fluidity.

This model replaces the older sandwich/unit membrane model, providing a more realistic and flexible view of membrane structure.

This model successfully explains many features of the cell membrane, including flexibility, self-healing, selective permeability, and membrane protein function.

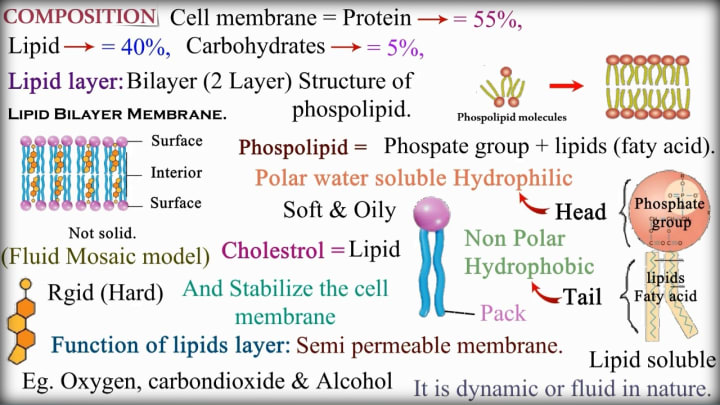

Composition of the Cell Membrane

The cell membrane is primarily composed of three types of molecules:

Proteins – 55%

Lipids – 40%

Carbohydrates – 5%

These components work together to form a semi-permeable membrane that controls what enters and exits the cell.

Lipid Bilayer Structure: The lipid layer forms a bilayer (two layers) structure, which is the foundation of the membrane. It is made up of phospholipids, each consisting of:

A polar (hydrophilic) head → water-attracting

A non-polar (hydrophobic) tail → water-repelling

This structure ensures that the membrane forms a flexible barrier with hydrophilic surfaces and a hydrophobic interior, allowing only lipid-soluble substances like oxygen, carbon dioxide, and alcohol to pass through easily.

Phospholipids and Cholesterol:

Phospholipids = Phosphate group + fatty acids

These molecules arrange themselves in two layers, with the tails facing inward and heads facing outward.

Cholesterol (a type of lipid) is also embedded in the bilayer:

It is rigid (hard) and stabilizes the fluid membrane

Prevents it from becoming too soft or too rigid

Fluid Mosaic Model Reinforced:

The membrane is not solid—it is soft, oily, and dynamic.

It moves like a fluid, allowing embedded proteins and lipids to shift and float.

This reinforces the Fluid Mosaic Model of membrane structure.

Function of the Lipid Layer:

Acts as a semi-permeable membrane, letting some molecules pass while blocking others.

Ensures homeostasis within the cell.

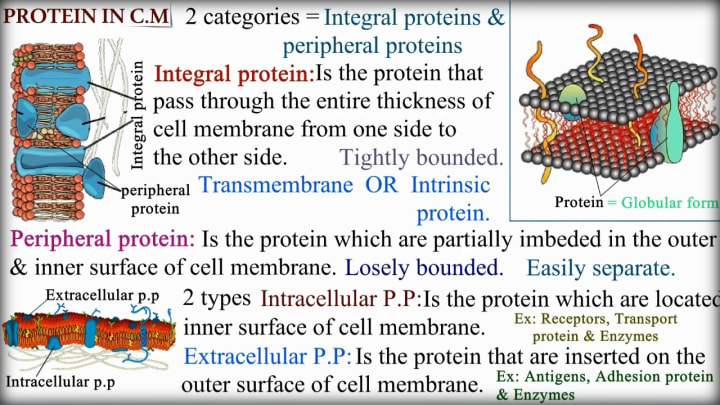

Proteins in the Cell Membrane (C.M.):

The proteins embedded in the cell membrane play vital roles in transport, communication, and cell structure. These proteins fall into two major categories:

1. Integral Proteins (Transmembrane or Intrinsic Proteins)

These proteins span the entire thickness of the cell membrane — from one side to the other.

They are tightly bound within the membrane.

Also called transmembrane proteins or intrinsic proteins.

Usually found in a globular shape, inserted within the lipid bilayer.

Functions: Act as

Receptors (receive signals)

Transport proteins (allow passage of molecules)

Enzymes

2. Peripheral Proteins:

These are partially embedded on the outer or inner surface of the membrane.

They are loosely bound and can be easily separated.

Do not span the membrane.

Peripheral proteins are of two types:

a) Intracellular Peripheral Proteins

Found on the inner surface of the membrane.

Function: Help in cell signaling and internal structural support.

b) Extracellular Peripheral Proteins

Located on the outer surface of the membrane.

Function: Involved in cell recognition, adhesion, and enzyme activity.

Examples:

Antigens.

Adhesion proteins.

Enzymes.

By understanding the placement and roles of these proteins, we can appreciate how dynamic and functional the cell membrane really is — not just a barrier, but a communication hub and transport system!

Functions of Proteins in the Cell Membrane

This slide outlines the critical roles that proteins play in the cell membrane. Let me break it down for you:

1. Structural Support (Integral Proteins)

Integral proteins are embedded within the cell membrane and provide structural integrity, helping maintain the membrane's shape and stability.

2. Transport Functions:

Channel proteins: Act like tunnels allowing water-soluble (polar) substances like glucose and electrolytes to pass through the otherwise nonpolar cell membrane.

Carrier/Transport proteins: Move substances across the membrane using either active transport (requiring energy) or passive transport.

Pump proteins: Special carrier proteins that actively transport ions (like sodium and potassium) across the membrane.

3. Communication (Receptor Proteins)

These proteins serve as docking stations for hormones and neurotransmitters, allowing cells to receive and respond to chemical signals.

4. Enzymatic Activity

Some membrane proteins function as enzymes, controlling and speeding up chemical reactions at the cell surface.

5. Immune Response

Certain proteins act as antigens - identifying markers that can trigger antibody production as part of the immune response.

The Architectural Proteins

Imagine a building's steel framework - that's what integral proteins do for your cells. They weave through the membrane's fatty layers, providing structure and stability to this delicate boundary that separates your cells from their environment.

The Cellular Doormen: Channel and Transport Proteins

Your cell membrane is like a bouncer at an exclusive club, deciding what gets in and out. Channel proteins create passageways for water-loving substances (like glucose) to slip through the membrane's otherwise water-resistant interior. Meanwhile, carrier proteins are more like personal escorts, carefully transporting molecules across the membrane barrier. Some even work as molecular pumps, using energy to move ions against their natural flow - crucial for nerve impulses and muscle contractions.

The Cellular Communication Network

Receptor proteins are your cells' information receivers. When a hormone like insulin arrives, it docks at these protein receptors, triggering a cascade of events inside the cell. This is how your body coordinates everything from metabolism to mood.

The Tiny Chemists

Some membrane proteins double as enzymes - biological catalysts that speed up chemical reactions right at the cell surface. These molecular machines make sure essential processes happen quickly and efficiently.

The Security System

Your immune system relies on membrane proteins to identify friend from foe. Certain proteins serve as identification tags (antigens) that can trigger antibody production when foreign invaders appear.

Why This Matters

Understanding these protein functions helps explain:

How nutrients enter your cells

How your body maintains balance (homeostasis)

How medications work (many target these proteins)

What goes wrong in diseases (like cystic fibrosis, where chloride channels malfunction)

Conclusion:

The next time you think about your body's incredible complexity, remember the unsung heroes - the membrane proteins working tirelessly in every single one of your 30 trillion cells. These microscopic marvels prove that big things really do come in small packages!

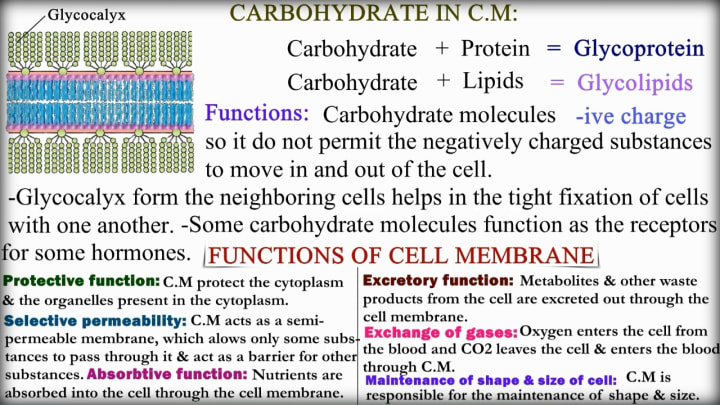

The Sweet Protective Coat: Glycocalyx

Every cell wears a sugary coat called the glycocalyx ("sugar covering"), made of:

Glycoproteins (sugar + protein)

Glycolipids (sugar + fat)

This coating serves as:

Nature's Force Field: Its negative charge repels harmful substances that might damage the cell

Cellular Glue: Helps cells stick together in tissues (imagine how important this is for your skin or organs!)

Molecular Mailbox: Recognizes and captures specific hormone messages

The Membrane's Marvelous Multi-tasking

Your cell membrane is the ultimate all-rounder:

The Ultimate Bouncer

As a selectively permeable barrier, it carefully vets every molecule trying to enter or exit. Water? Welcome. Essential nutrients? Come on in. Harmful substances? Not on its watch!

Nutrition Gatekeeper

The membrane doesn't just block - it actively helps absorb nutrients your cell needs to thrive, working like a sophisticated feeding system.

Waste Management

Cellular trash (metabolites and waste) gets efficiently excreted through the membrane - nature's perfect recycling system.

Breathing Apparatus

Oxygen in, carbon dioxide out - the membrane handles this vital gas exchange that keeps your cells energized.

Cellular Sculptor

By maintaining structural integrity, the membrane gives cells their distinct shapes - from round blood cells to branching neurons.

Why This Matters to You

Understanding cell membranes helps explain:

How nutrients are absorbed in your gut

Why some medications need special delivery methods

What goes wrong in conditions like cystic fibrosis

How cells communicate in your immune system

Conclusion:

Next time you look at your skin, remember - each of your cells has its own even smarter protective layer working 24/7. These membranes aren't just walls; they're intelligent interfaces that make life possible at the microscopic level.

Fascinated by how your body works at the cellular level? Share which membrane function amazed you most in the comments! #CellBiology #HumanBody #ScienceSimplified

Bonus Thought:

Your entire body exists because trillions of these smart membranes work in perfect harmony - nature's ultimate team players!

About the Creator

EasyMedEdHub

Welcome to EasyMedEdHub! 🎓

EasyMedEdHub simplifies complex science and medical concepts with clear, engaging content. Follow for tips, insights, and resources to help you succeed academically in biology and beyond!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.