Frappés to Facts: A Quick Introduction on Type I and Type II Diabetes

Grab some food and digest the basics on diabetes!

As I sat in my car drinking my large McDonald's Mocha Frappé, I had nothing better to do than see how much sugar there was; frankly, I should not have looked - there were over 70 grams of added sugar. Looking at the shake like a disappointed dad, I did nothing but continue loving it. All 70+ grams of sugar were consumed. In justification, I convinced myself that I needed the entire frappé to function - it’s like how I fully filled up my car with gas. Same difference. And, so, as I drove home, I led with the mentality that I was a car that needed a full tank.

Maybe that’s a little exaggerated, but I’m sure people have compared our bodies to cars, right?

Cars need fuel to run, and we need fuel to walk… and run! Once we have the fuel, we will have to make it available for energy. For cars, this could be as simple as having gas or diesel to press the accelerator so that the car can move. Humans have a similar system: our fuel is the food we eat, namely carbohydrates. While there are many forms of carbohydrates, they are broken down into glucose - the simplest sugar - for energy (Holesh et al., 2023). Yes, yes, I know - you may have heard of fructose, the “natural fruit sugar,” and sucrose too; these are also carbohydrates, but interestingly, our body converts fructose into glucose! As for sucrose, it is a two-sugar system made up of glucose and fructose (and you guessed it, that fructose is converted to glucose) (Dholariya and Orrick, 2022). Glucose is now in our bloodstream, leading us to say “blood sugar;” this simply refers to the idea that there is sugar in our blood. Of course, if you want to be more specific and sciency, you can say “blood glucose” - you got it!

However, we aren’t always getting new glucose! Of course, we have our safe deposit box and our Glucose Savings Account - the liver: After a meal, maybe you don’t need to use any glucose for energy, but regardless, we still need the sugar out of our bloodstream since our blood glucose is high - we can’t have free-flowing cash! Our pancreas releases insulin, a hormone or chemical messenger, into our bloodstream to recruit and pull out glucose (Watson, 2019). Normally, insulin lowers blood-glucose by helping cells - functional units of organs - absorb it. One of the first places glucose enters is the liver, which will stay until later used by the rest of the body. The other two main sites for glucose entry are muscle and fat, which will be discussed briefly later (Watson, 2019).

However, for some individuals, insulin does not get produced or does not function properly. As a result, people develop type I or type II diabetes - the two types of diabetes we will be discussing today.

Type I Diabetes:

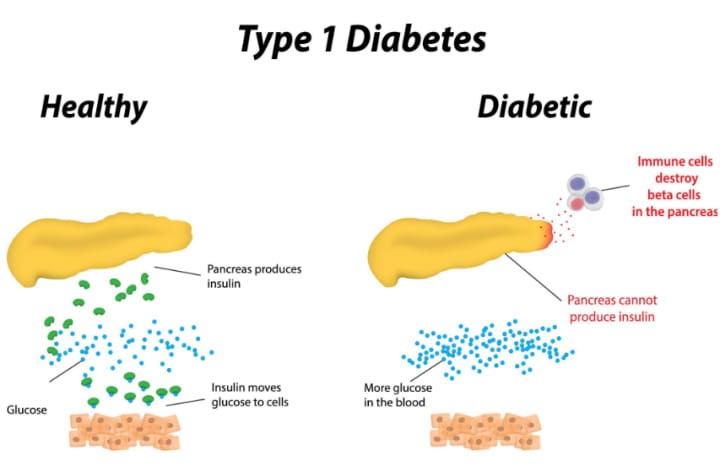

I like to remember the “I” in type I diabetes for “self.” Type I diabetes arises mainly due to an autoimmune attack - an individual’s immune system mistakenly considers specific organs or cells to be outsiders; the immune system then works to destroy these specific parts (Cleveland Clinic, 2024). Here, the targeted cells are the “beta cells” - the insulin-producing cells - of the pancreas. With destroyed insulin-producing cells, very little insulin will be made; if the amount of insulin is low, even if we have a buildup of glucose in the blood after we eat a meal, we will not be able to decrease the blood glucose level (American Diabetes Association, 2024). Although genetic and environmental factors are commonly attributed to this autoimmune attack and type I diabetes, the exact cause is not exactly known (Mayo Clinic, 2024).

Type II Diabetes:

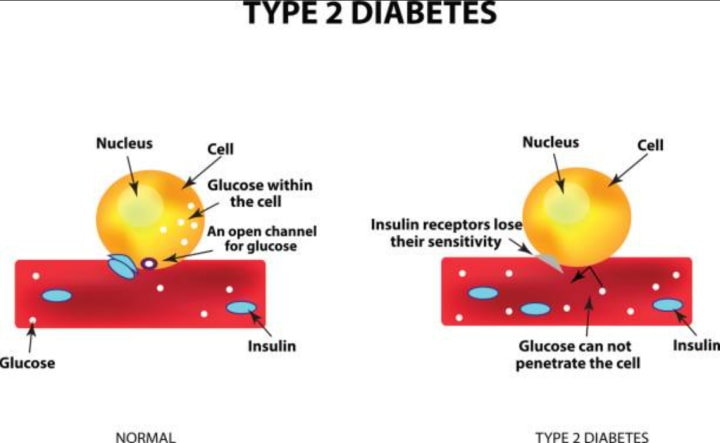

Essentially, while insulin is still produced, the body cannot use it very effectively, which prevents glucose from leaving the bloodstream and entering cells; the body’s inability to properly use insulin is known as insulin resistance (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2018). So what happens? Assuming “more is better,” the pancreas continues producing insulin, hoping that a larger quantity of the hormone will overcome the resistance. Gradually, the pancreas accepts defeat as it is exhausted and overworked - its beta-cells are working in vain, and insulin production significantly declines (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2024). Consequently, glucose will remain in the bloodstream, leading to high blood glucose. Think about it like this: a mom calls her son to come down for dinner, but the kid does not leave his room. In sheer desperation, the mother continues screaming her son’s name, hoping he will eventually exit. Eventually, the exhausted mother stops; she looks up the stairs, quietly shakes her head, and walks away - no more shouting, and the son will stay in the room.

Fortunately, causes for type II diabetes are more well-known and are not caused by an autoimmune condition. Risk factors of type II diabetes include, but are not limited to, genetics/family history, age, obesity, and a lack of physical activity (CDC, 2024). We cannot fully control genetics, but lifestyle factors can attenuate susceptibility to type II diabetes. While I cannot give any expert recommendations, speaking with a dietitian to find a food program can be essential; subtle dietary changes, such as decreasing carbohydrate intake or increasing fiber intake, can help mitigate blood glucose levels. As obesity is a risk factor, exercise is crucial: going to the gym, participating in recreational sports, or even using a treadmill for a few hours during the week. With appropriate meals and exercise, there is a greater probability that an individual will lose fat. Lower body fat contributes to suppressing insulin resistance, which in turn, helps control type II diabetes. For more information regarding healthy habits with diabetes, you can visit this page; I do not take credit for any of the content posted there.

Preexisting health conditions are also determinants of potentially developing type II diabetes, such as atypical cholesterol levels. Although various health issues make an individual prone to type II, here, the concern I want to focus on is damage to blood vessels.

Why is this an issue? Well, let’s talk science and finance.

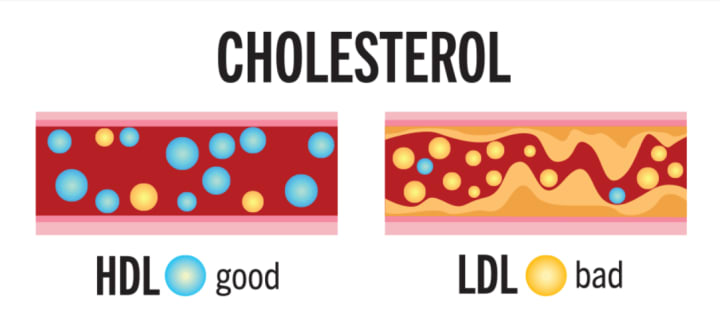

We know that insulin pulls out glucose from our bloodstream, meaning that insulin has to travel throughout our blood vessels. Again, we have our glucose - our cash - flowing casually within our bloodstream - our wallet. We need our hands to enter the wallet, which is what insulin is! But imagine our wallet is saturated with credit cards, hotel cards, receipts, and old high school ID cards; it would be terribly difficult to find that cash trapped inside! This is where we get our atypical cholesterol levels. Namely, there are two main types of cholesterol, which are types of fat: good cholesterol and bad cholesterol. No, no, I didn’t choose which one is good or bad, and I’m not making it up either! Yes, they have scientific names, but the key to understanding the function and levels of good and bad cholesterol, both found in our blood: bad cholesterol can build up and cause plaque buildup, while good cholesterol attempts to prevent plaque formation by removing bad cholesterol (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2021). Unfortunately, whether it be high bad cholesterol levels, low good cholesterol levels, or a combination of both, the blood vessels, specifically arteries - the blood vessels that transport oxygen and nutrients to organs away from the heart to specific parts of our body - are soon clogged with plaque; this plaque raises the risk of cardiovascular problems, including heart disease and stroke. So yes, unfortunately, a history of heart disease and stroke is also a risk factor for type II diabetes (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2021). High amounts of bad cholesterol levels also result in inflammation, which disrupts the efficient use of insulin for the muscle, liver, and fat cells.

Similar to how it’s hard to find your cash when there’s a bunch of cards and receipts, glucose is difficult to pull as the insulin has trouble traveling through the arteries clogged with plaque, heightening insulin resistance.

Common Symptoms for Type I and Type II Diabetes:

Of course, not all patients will experience all symptoms, and the severity of the symptoms can vary from individual to individual. However, in terms of type I and type II diabetes, two common symptoms I want to highlight are increased thirst and frequent urination; in medical terms, increased thirst is called polydipsia, and frequent urination is called polyuria.

Polydipsia and Polyuria:

“Poly” means “a lot,” “many,” or “much,” just like it would if we are talking about the words polyglot, polygamy, or even polygon!

But how do I remember “dipsia” and “uria”? At face value, “dipsia” means “thirst;” I think of “dipsip” - I sip (on water) when I feel “dipsia” (thirsty)! Using this made-up word, it becomes easier for me to remember that polydipsia means excessive thirst.

As for “uria,” it is a little simpler since urine and uria sound alike! So, when we add “poly,” we get “polyuria”: excessive urination.

I’m sure from these two symptoms you may see the ongoing loop; if someone drinks a lot of fluid, they will have an urge to urinate more. Conversely, if an individual has to pee a lot, they will want to drink more water!

But why does this happen in the first place? We know that whether an individual has type I or type II diabetes, it is difficult for insulin to take all of the glucose from the bloodstream in a timely manner. Now … this is a problem for our kidneys…

Our kidneys are like kids; while kids trade Pokémon cards and get rid of unwanted ones, kidneys trade with the blood and get rid of wastes, substances, and excess fluids to release healthy urine. During the initial interaction between the kidney and blood, the kidney will take all the basic substances the blood offers, including all the glucose. Slowly, the kidney will give back the substances - Pokémon cards - that they think would not suit urine.

With patients with type I or type II diabetes, there is a surplus quantity of glucose unable to leave the urine. The abundance of glucose causes fluid, such as water, from the body’s tissues, which are components that make up organs, to go into the urine; essentially, the surplus of glucose causes the kidneys to bring in more water, causing more urination (Bonn and Connell, 2024). Resultingly, the individual becomes dehydrated, causing the person to feel more thirsty since there is greater fluid loss than in an individual who does not have glucose in the urine (Bonn and Connell, 2024). At the same time, as glucose - a sugar - exits the body in the urine, another common symptom is sweet-smelling pee (Bonn and Connell, 2024).

So, was the large worth it? Honestly, I would have it again - the frappe led me to write this article. Of course, I won’t be overdosing on 70 grams of sugar every day. And, at the same time, there are variables outside of my control. Sure, we may be like cars - which, I’m not even sure if that’s true - but I think a small is just enough next time.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.