Enceladus: The Moon That Sprays Secrets of Life Into Space

Space

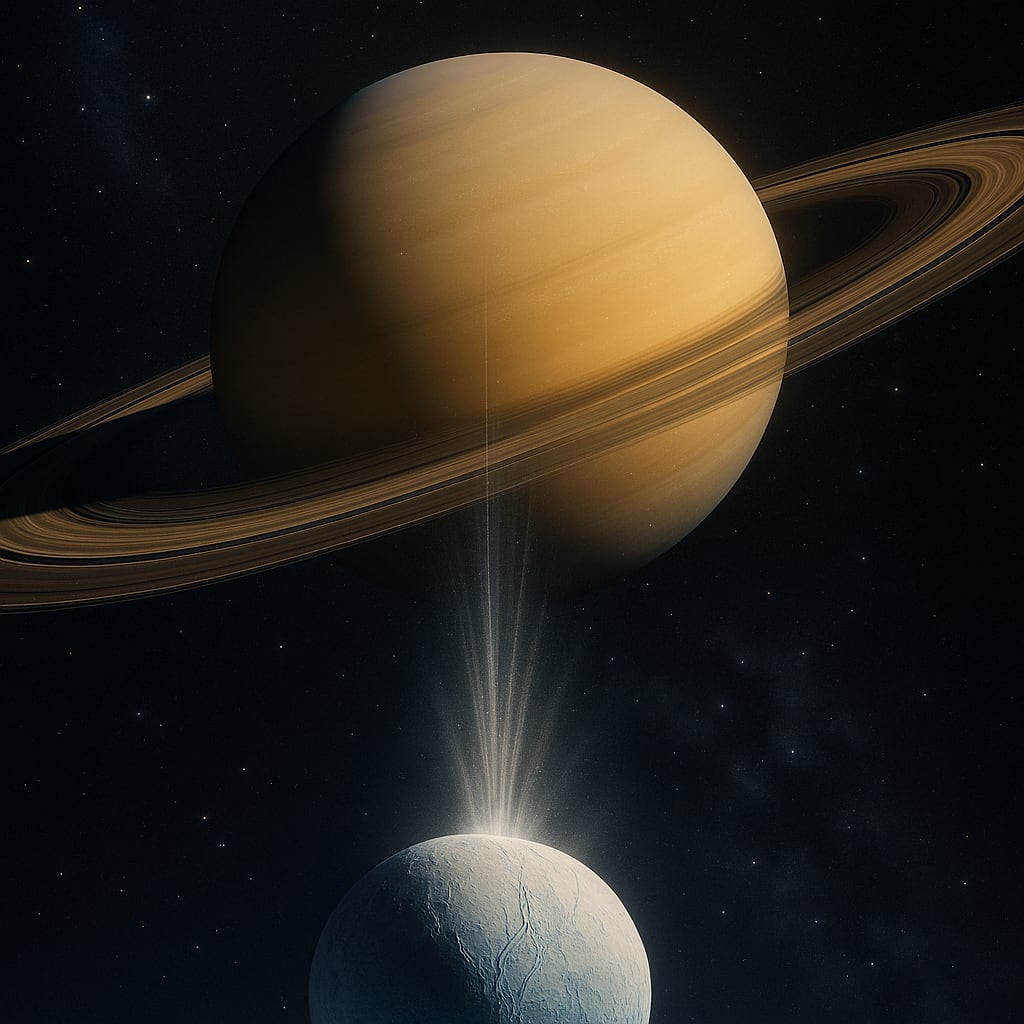

When astronomers first discovered Enceladus, one of Saturn’s many icy moons, few suspected it would become one of the most exciting places in the solar system. Barely 500 kilometers across, this tiny world seemed frozen, silent, and geologically dead. But in 2005, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft made a discovery that shocked scientists — Enceladus wasn’t dead at all. It was alive with activity, shooting enormous plumes of water vapor and ice particles far into space.

Those shimmering geysers, erupting from deep cracks near the moon’s south pole, transformed Enceladus from a distant ice ball into a top contender in the search for alien life.

The Space Geysers That Changed Everything

Cassini first spotted the plumes as mysterious jets silhouetted against the blackness of space. They erupted from long, warm fissures now nicknamed “tiger stripes.” When the spacecraft flew directly through these plumes, it sampled the frozen mist — and what it found was extraordinary.

The ejected material contained salty water, organic molecules, carbon dioxide, ammonia, and methane. These aren’t just random chemicals; they are the essential ingredients for life as we know it. Even more astonishing, Cassini’s instruments detected microscopic grains of silica, the same mineral that forms when hot water reacts with rock on the ocean floor. That means Enceladus isn’t just icy — it’s home to a global subsurface ocean, kept liquid by the moon’s internal heat.

So, beneath a crust of ice dozens of kilometers thick lies a warm, salty ocean, and in that ocean, hydrothermal vents may be pumping energy-rich chemicals into the water — just as they do in Earth’s deepest seas.

Life Without Sunlight: Lessons from Earth

On our planet, sunlight is the foundation of nearly all ecosystems. Yet in the pitch-black depths of the oceans, where sunlight never reaches, life thrives around hydrothermal vents — underwater geysers that spew hot, mineral-rich water. Here, bacteria feed not on light, but on chemical reactions, in a process known as chemosynthesis. These bacteria support entire ecosystems of strange, beautiful creatures: giant tube worms, glowing shrimp, and ghostly white crabs.

If similar vents exist on Enceladus — and evidence suggests they might — then this little moon could host its own alien ecosystem. Microbes could be floating in its subsurface sea, feeding on hydrogen and carbon compounds, just as life began on Earth billions of years ago.

Cassini’s Legacy: A Taste of the Ocean Beyond

During its daring flybys, Cassini effectively “tasted” Enceladus’s spray. By analyzing the composition of the particles, scientists discovered molecular hydrogen (H₂) — a telltale sign of hydrothermal reactions. On Earth, such reactions between hot rock and water produce energy that microbes eagerly consume.

That single detection turned Enceladus from “intriguing” to “potentially habitable.” While Cassini couldn’t directly detect living organisms, its data strongly suggest that the moon meets all three key conditions for life: liquid water, organic chemistry, and a source of energy.

When Cassini ended its mission in 2017 by diving into Saturn’s atmosphere, it left behind a mystery far greater than anyone expected: could Enceladus’s ocean actually be alive?

The Future: Missions to Uncover the Mystery

Scientists around the world are now designing missions to return to Enceladus — not just to fly through its plumes, but to study them in exquisite detail or even land on the surface.

One of the most promising proposals is NASA’s Enceladus Orbilander, a spacecraft that would first orbit the moon, then touch down near its south pole. The Orbilander would sample the freshly fallen plume material, searching for biosignatures — chemical traces that could only be produced by living organisms. These might include complex organic molecules, unusual isotopic ratios, or even simple amino acids arranged in patterns suggesting biology.

Another concept, led by international teams, envisions sending a cryobot — a robotic probe capable of melting through the ice to reach the hidden ocean directly. It’s an audacious idea, but one that could answer one of humanity’s oldest questions: Are we alone?

Why Enceladus Matters

Enceladus has redefined what “habitable” means. Before Cassini, scientists believed life required a planet close enough to its star for liquid water to exist. But Enceladus orbits nearly a billion miles from the Sun, its ocean kept warm not by sunlight, but by tidal heating — the gravitational flexing caused by Saturn’s immense pull.

This discovery proved that life might not depend on distance from a star at all. It could exist in dark, hidden oceans beneath the icy shells of moons — worlds that outnumber planets in our solar system.

A Tiny Moon With a Big Message

Enceladus reminds us that the universe is full of surprises. A small, icy moon barely larger than England might hold the ingredients — or even the presence — of life itself. Its shimmering plumes are more than just frozen spray; they’re messages from a hidden ocean, whispering that the story of life might be far more universal than we ever imagined.

Someday, perhaps soon, a spacecraft will catch one of those icy particles and tell us definitively whether something swims beneath that frozen shell. Until then, Enceladus continues to inspire — a brilliant beacon of mystery, 1.4 billion kilometers from home.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.