What Sea Turtles See That We Can’t See

We have five senses, but they have superpowers…

“At the time of writing, magnetoreception remains the only sense without a known sensor.” — pg. 320, An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us,” Ed Yong, Penguin Random hardcover (2022)

We know they do it. We can see them do it. Baby turtles, no bigger than a minute. Warblers and hummingbirds, smaller than the baby turtles even as adults. They decide where they’re going, and they just go there.

Without a map folded and unfolded and hopelessly crumpled. Without the guidance of a friendly satellite beaming down instructions from outer space.

It shouldn’t work, and yet it does.

Sure, an unlucky reverse lottery winner sometimes drifts off track. But the lost creature is the rare oddball. If somebody spots an out-of-place bird, they fire up the rare bird alert so we can hop in our cars all loaded down with cameras to see for ourselves.

It’s a rare occasion.

In their millions, the overwhelming majority of them go where they intend to go.

But how? It seems so implausible.

If millions of us hit the road, you’d better believe a lot of us are making a lot of wrong turns.

Consider the leatherback sea turtle. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), this endangered migratory species travels as much as 10,000 miles a year between their feeding grounds and the nest site where they lay their eggs. [Source]

The first time they head out to their feeding grounds, they’re babies all alone. No adult leads them on their way.

“By the 1990s, no one had worked out how inexperienced [sea] turtles could pull off such grand migrations — a state of ignorance… lamented as ‘an insult to science.’ … Ken Lohmann couldn’t understand the fuss. Armed with a newly acquired PhD and the hubris of youth, he thought the answer was obvious: The turtles must use a magnetic compass. It would be a simple matter [to prove]… He had signed up for a two-year project, and ‘my main concern was what I would do for the second year,’ he tells me. ‘That was over 30 years ago. The only part I got right was that they have a magnetic sense.’ … [T]hey [actually] have two.” — pg. 307, An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us,” Ed Yong, Penguin Random hardcover (2022)

Well, it’s complicated, the scientists say. We’re still fighting over it, they say.

There might be a Nobel Prize in it. There might be money. Defense applications.

We humans, as a species, started so far behind the rest of the animal kingdom that we’ve got a lot to figure out. For thousands of years, our feeble sensory equipment forced us to rely on magic stones and the sky above to tell us where we were.

Shorn of our maps, GPS devices, and smartphones, many Americans start by buttonholing somebody else who looks like they know where they’re going.

Sometimes, that works. And sometimes that’s dangerous. Then it’s time to raise our eyes to the heavens.

A rising sun is in the east, and a dropping sun is in the west. The moon does the same, but the moon isn’t always there. So we’re taught — or used to be taught, for Florida has perchance made such teachings illegal — how to spot the Dippers and thus the North Star.

But what if the sky is cloudy?

That’s where the magic of stones come in.

If it isn’t too sassy, I’ll quote from my own book, Crystal Magick, Meditation, and Manifestation: A Crystal Book of Shadows:

The North Atlantic seas are often cold, stormy, and blanketed by clouds. If you can’t see the stars at night or the sun by day, how do you keep from somehow sailing backward and ending up in Canada? Well, all right, at least once I suppose they did sail the wrong way and end up in Canada, but most of the time, the Vikings seem to have got where they intended to go.

So how did they do it?

The Icelandic sagas say they used sunstones... They held the stone up to the sky, and it told them where the sun was hiding behind that cloud bank, and then the sailors could do a little figuring, and they’d know where to go.

But the stone we know today as sunstone doesn’t do that. A mystery.

A piece of Iceland Spar found on a centuries-old wreck gave historians the clue they needed to solve this puzzle. Optical Calcite’s property of splitting one ray into two rays of light can be used to detect where the sun is hiding. Clouds aren’t fooling this little stone.

Another stone, beloved of New Orleans gamblers, is Lodestone (magnetite). Used as a compass for thousands of years, magnetite will always point North if suspended in a frame that allows it to move freely.

And we weren’t the only species to do that — or so we thought.

For decades, we alleged moderns thought the uncanny homing abilities of Homing Pigeons could be attributed to tiny magnetite crystals in their brains.

No, please, stop laughing! We really believed this. Not just humble Bird Talk writers such as myself. Everybody of my generation believed it.

Ed Yong notes that this theory was debunked in 2012. The magnetite we were told was there in pigeon brains… wasn’t. Oopsy. [An online source is here. Read to the end.]

So how do they do it? A disreputable-looking pigeon wants to go somewhere, and they just go, and I want to go somewhere, and I just get lost, and it all feels like magic.

It also feels like one day we’ll figure it out.

Iceland Spar isn’t just a gift of the sun god to help Vikings find their way when the sun god himself is too busy to blast away the clouds. It possesses a real optical property that helped them guide their ships.

Lodestone isn’t just something to drop in your pocket when you’re hoping to find a beatable dice game. It really is a natural magnet.

The turtles keep getting where they’re going. The homing pigeons get there. The migrating birds get there. Even paper wings like Monarch butterflies get there.

One day, we’ll find out how.

And, on that day, as on every other day, it will still feel like magic.

How do their brains do that? How do they know?

An Awesome Encounter with Leatherback Turtles

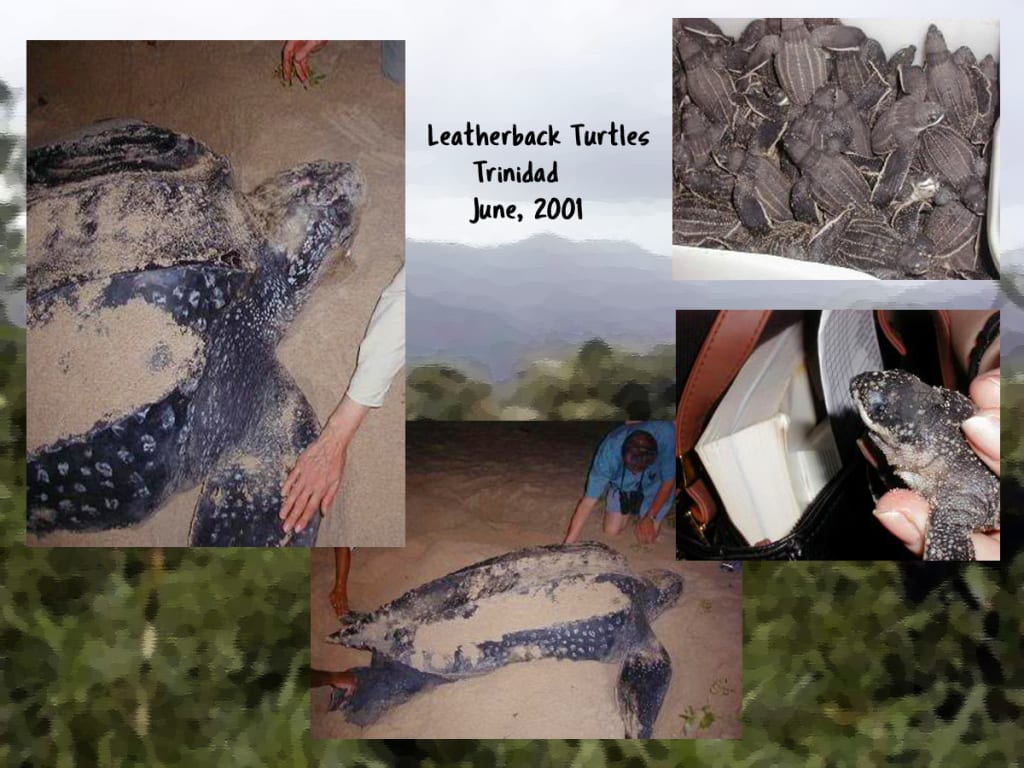

The photographs in the feature image were taken with the first digital camera I ever owned, an Epson something or other, during a visit to Trinidad in June 2001. On this particular evening, we’d been guided to a beach set aside for sea turtles.

The guides confidently predicted that one of the known nests would hatch. (It did.) Because it was a moonless night, they also predicted that a secretive mother would slip in to lay her eggs on the beach.

My equipment was primitive. The Epson which seemed so digital and fancy in 2001 had laughably few megapixels. Blown up to size, the individual photos were too blurry to be used alone for a feature.

Therefore, I created a collage from five images. The background image is a mountain view, suitably blurred with the use of Photoshop’s watercolor filter.

Starting from the upper right and moving clockwise, you can see a large number of baby turtles that hatched in the late afternoon. We were tasked with taking those turtles safely down to the sea before the (literally hundreds) of waiting Black Vultures swooped down to feast.

You can see the one I released into the sea. All together now: “Awwwww.”

After the babies were safely on their way — to the disgust of the Black Vultures — we waited in total darkness.

No lights could be used until the mother turtle was deep into the egg-laying trance. They rely completely on invisible guidance from their magnetic sense to find their home beaches. Otherwise, their enemies would simply watch, wait, and dine on omelets once Mama Turtle headed back out to sea.

In 2001, the no-light rule was easy to enforce. Phones weren’t also flashlights then. Heck, some of them weren’t even phones, just pagers.

Because of the total darkness, and the near silence of her approach, I had no idea how large she was — or how close — until the guide switched the flashlights on. I must have jumped ten feet.

Imagine being from Louisiana, and seeing something the length of a granddaddy alligator at your feet. Except that it was thicker — thus even bigger — than an alligator.

Good thing the egg-laying trance is a real thing, because I’m pretty sure I squealed.

This endangered migratory species is the largest turtle in the world. But that’s just words until you’re within touching distance of one of these gentle giants.

Author's Note

This story was originally published on Feb. 27, 2023 in For Awe, a Medium publication. If you enjoy reading these stories without a paywall, please consider leaving a <3 or a comment. Thanks!

About the Creator

Amethyst Qu

Seeker, traveler, birder, crystal collector, photographer. I sometimes visit the mysterious side of life. Author of "The Moldavite Message" and "Crystal Magick, Meditation, and Manifestation."

https://linktr.ee/amethystqu

Comments