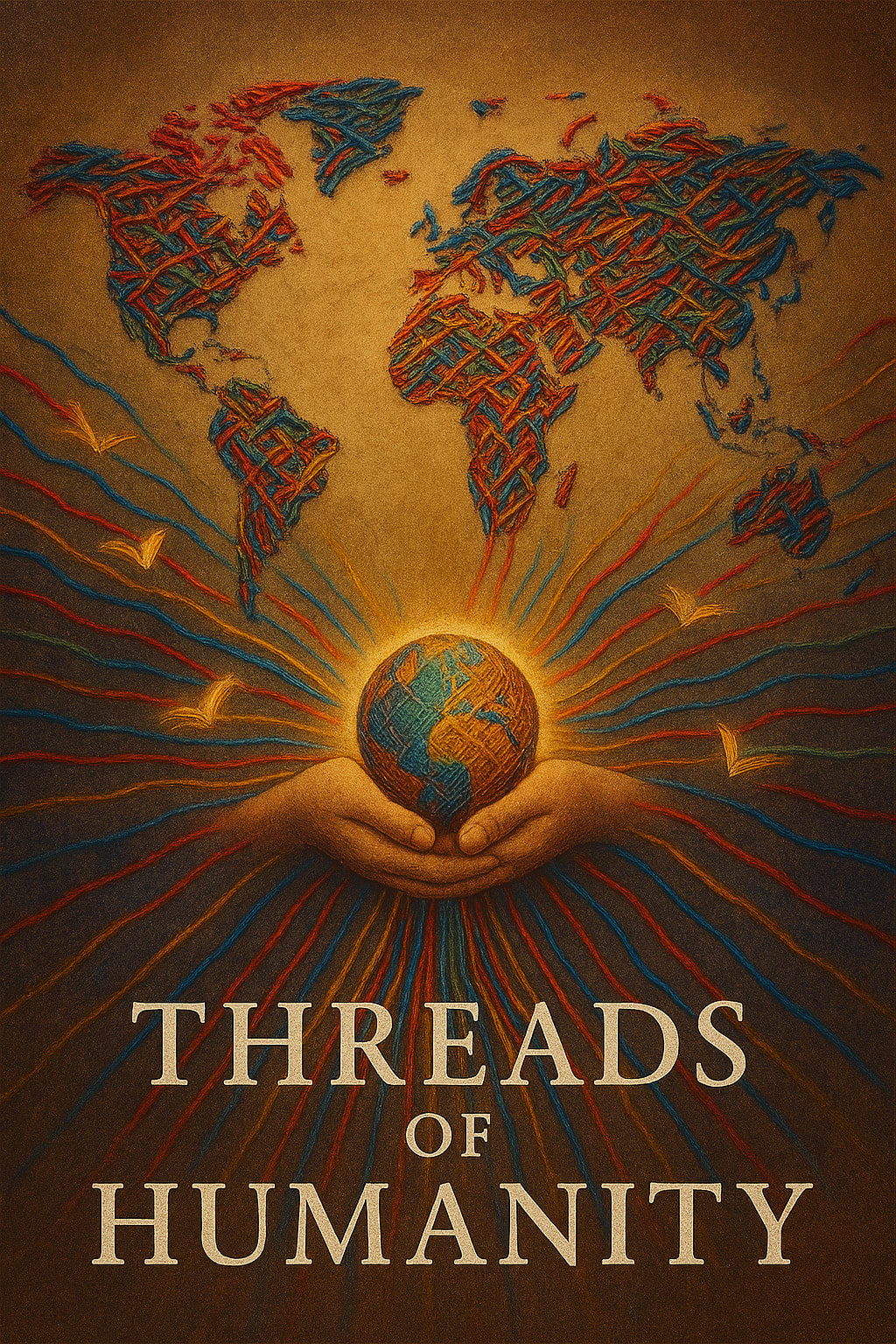

"Threads of Humanity"

showing how cultures connect us

When I first decided to travel across the world with nothing but a backpack and a camera, I thought I was simply collecting stories. I thought I would be a witness, a passerby, someone who observed the world and captured its beauty through my lens. But as I stood in the middle of a bustling market in Marrakech, surrounded by the sound of bargaining, the scent of spices, and the heat of the desert sun, I realized something else entirely. I wasn’t just observing—I was becoming part of something bigger.

The idea for my documentary had been simple at first: to capture “human connection.” It sounded poetic enough for a funding proposal, but I had no idea what it meant in practice. My first stop was Morocco, where I followed an elderly weaver named Hassan into his small workshop.

The room smelled of dyed wool and desert dust. His hands, worn and strong, moved rhythmically over the loom as if they had memorized this dance long ago. I asked him, through a translator, why he still wove rugs by hand when machine-made ones sold for cheaper. He smiled, a slow, wise smile, and said,

“A machine can make a rug, but it cannot put a story in it. Each thread remembers the hands that touched it, the thoughts that shaped it.”

His words stayed with me as I filmed the loom’s wooden frame clacking, the threads slowly forming intricate geometric shapes. Hassan showed me a finished rug, a riot of reds and blues. “This one,” he said, “is for a wedding. It carries blessings for the couple. When they walk on it, they will be walking on the hopes of everyone who helped make it.”

From Morocco, I traveled east to India. In Varanasi, I sat by the Ganges at sunrise, watching the river reflect gold and orange as hundreds of people gathered for their morning rituals. Nearby, women washed clothes, monks chanted, and children splashed in the water. A boatman named Ravi offered to take me across the river. As we floated, I asked him why so many people came here every day.

“The river reminds us,” he said, dipping his hand into the water, “that we are all part of the same flow. You and I, stranger, we are drinking from the same current.”

That night, I recorded the ceremony of lamps — dozens of priests lighting fire bowls and swinging them in unison. The flames danced against the dark river, a ritual that had been performed for centuries. Watching it, I felt something stir deep inside me — as if I was witnessing not just a ceremony, but a thread connecting past and present, strangers and kin.

In Peru, I climbed to a village in the Andes where the air was thin and the sky close enough to touch. There, I met Rosa, a woman who dyed alpaca wool using plants she grew herself. She showed me how the greens came from leaves, the purples from cochineal, the yellows from flowers. Her hands were stained from years of work.

“These colors are alive,” she told me. “They fade if we don’t care for them, just like our traditions.”

She wrapped a finished shawl around my shoulders and said, “Now you carry our mountain’s story with you.”

Each stop became a thread — Morocco, India, Peru — each person a weaver in their own way. The footage I gathered was breathtaking: children in Senegal playing drums as if their hands were born knowing the rhythm, a family in Mongolia sharing salty milk tea in their ger, elders in Japan folding origami cranes for peace.

But it wasn’t until my final stop in Greece that I truly understood the heart of my journey. I stayed with an old fisherman named Theo on a small island in the Aegean Sea. Each morning, he took me out on his boat as the sun painted the water pink. One evening, after sharing a simple dinner of grilled fish, I asked him what he thought about the world beyond his island.

He gazed out at the horizon and said,

“The sea has many waves, but it is one water. People are like that too. We think we are separate, but we are not. If something touches one wave, it touches them all.”

When I flew back home months later, I sat in the editing room with hours of footage and hundreds of notes. At first, I tried to separate the stories — one chapter for Morocco, one for India, one for Peru. But it didn’t feel right.

That’s when I realized what Hassan had meant on that very first day. Each story was a thread, yes — but they were not meant to stand alone. They were meant to be woven together, forming something larger, something whole.

When the final documentary was done, the opening shot was simple: a single thread stretching across the screen. Then another crossed it. And another. Slowly, as the narration began, the threads wove together until they formed a globe.

“We are not just observers of the world,” my voice said in the narration, “we are part of it. Each life, each culture, each tradition is a thread — and together, we are the fabric of humanity.”

When the lights came up at the film’s first screening, there were tears in the audience. Not because the film was sad, but because it reminded them of something easy to forget in a world so divided: that no matter where we are from, we are connected.

And as I stood there, watching strangers smile at each other, I knew the journey wasn’t just about filming the world — it was about feeling it.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.