Sharks Never Stop Moving… Or Do They?

Do sharks really die if they stop swimming? Discover the truth about how sharks breathe, rest, and even 'sleep' while on the move!

Imagine never being able to stop moving – not even for a second – or else you die. Sounds exhausting, right? This is the common belief when people think about one of the ocean’s apex predators, the shark. We all think they need to constantly swim in order to live but is that really the case? Let’s find out.

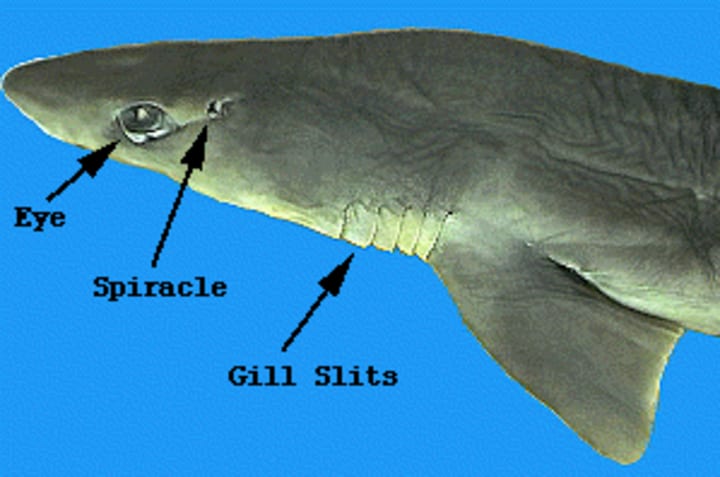

Well, first a bit of introduction about sharks. Sharks are a group of cartilaginous fish consisting of more than 500 species varying in size and shape. From the enormous whale shark to the tiny dwarf lanternshark, they come in all forms. However, they all share common traits such as ribless endoskeleton, dermal denticles, five to seven gill slits, and pectoral fins not fused to the head.

So, do sharks really die if they stop swimming? The answer is—it depends. Not all sharks breathe the same way. Surprising, right? Different species have evolved two distinct methods of breathing, and whether a shark needs to keep swimming or not comes down to how it gets oxygen. These two breathing methods are: ram ventilation and buccal pumping.

RAM VENTILATION

In the video above, you can see the shark swimming with its mouth constantly open showcasing ram ventilation.

Ram ventilation requires sharks to constantly swim. As they move forward with their mouths open, water flows in, passes over their gills and exits through gill slits. Oxygen is absorbed and carbon dioxide is released when water passes over the gills. Ram ventilation is more energy efficient than buccal pumping.

Some shark species can switch between the two breathing methods while others are adapted to only one. There are around 24 species of sharks that rely solely on ram ventilation and are thus called “obligate ram ventilators”. Examples include the great white, hammerhead, mako, salmon, sandbar, thresher, porbeagle, bull and whale sharks.

BUCCAL PUMPING

Buccal pumping is the process of using cheek muscles to draw water into the mouth. Simply put, the shark rhythmically opens and closes its mouth to push water over its gills for respiration. When the shark opens its mouth, the mouth floor lowers, increasing the volume and drawing in water. When the mouth closes, the floor rises, decreasing the volume and forcing water over the gills and out through the gill slits.

This method is used by benthic sharks or sharks that live near the bottom of the sea. Examples include nurse, bullhead, wobbegong, angel, zebra and epaulette sharks.

FACULTATIVE VENTILATION

So far, we know, we can divide sharks into two groups – ram ventilators and buccal pumpers – based on how they breathe. However, some sharks fall into a third category: facultative ventilators. These species can switch between buccal pumping and ram ventilation. Examples include tiger, blacktip reef and lemon sharks.

Most facultative ventilators and buccal pumpers possess spiracles—small respiratory openings located behind the eyes. Spiracles help draw in water, allowing sharks to breathe even when stationary. This adaptation is especially useful for bottom-dwelling species. For instance, wobbegongs, ambush predators that often bury themselves to camouflage, use their spiracles to continue breathing while hidden beneath the sand.

This understanding of shark respiration might spark another question: if sharks — except for obligate ram ventilators — don’t need to swim constantly, do they sleep?

Yes, sharks do sleep. However, the meaning of sleep in sharks is completely different from what it is in humans. Unlike us, they don’t go in a deep, unconscious state while lying on the ocean floor. Instead, shark sleep is a resting phase marked by a lower metabolic rate and reduced activity, allowing them to conserve energy while staying alert to their surroundings.

There is evidence of "sleep" in buccal pumpers. For instance, nurse sharks spend much of their time resting on the seafloor during the day. Sharks like Port Jackson, Caribbean reef, whitetip reef, and lemon sharks exhibit higher metabolic rates and increased activity at night, when it’s their time to hunt.

On the other hand, ram ventilating sharks show very little changes in their activity. These sharks show cyclic diel vertical migrations (DVMs) – a pattern in which they occupy different depths of the ocean at different times of the day. Species like the shortfin mako, blue shark, and whale shark tend to inhabit greater depths during the day and move closer to the surface at night. While DVMs might indicate rest in ram ventilators, they could also serve other purposes.

Another energy conservation strategy used by sharks is the “yo-yo” movement, where they actively swim towards the surface and then passively glide downward. This pattern may help sharks conserve energy or enter a resting phase. However, a study on tiger sharks, which were fitted with cameras and accelerometers, revealed images of prey encounters during these movements. This suggests that yo-yo movement could serve as both a hunting tactic and an energy-saving behavior.

RESTING WHILE SWIMMING

Sharks may be able to rest—or even "sleep"—while swimming. A study on spiny dogfish revealed that swimming is controlled by the spinal cord, and it can continue even without input from the brain. This is due to Central Pattern Generators (CPGs) — neural circuits that produce rhythmic movements without needing constant brain signals. In spiny dogfish, CPGs allow their tails to move in a rhythmic pattern, keeping them swimming automatically.

In simple words, CPGs are like built-in autopilot systems. They are neural circuits or like tiny highways that carry signals between interconnected nerve cells. They help control movements and reflexes even in the absence of any input so sharks don’t have to think about every move just like how we don’t have to think about every step we take.

This auto-pilot swimming mechanism in spiny dogfish and if present in larger sharks as well could indicate that they could rest even while swimming. However, despite relying on CPGs for movement, their brain is still a very important organ as it controls steering, navigation, sensing and responding, decision-making and coordination.

Here’s a video showing a great white shark napping for first time on camera:

REFERENCES:

https://www.elasmo-research.org/education/topics/b_sleep.htm

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00238013

https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/504123

https://www.int-res.com/articles/meps_oa/m424p237.pdf

https://a-z-animals.com/blog/do-sharks-sleep-and-how/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/sharks-apparently-do-sleep-even-with-their-eyes-wide-open-180979707/

https://poseidonsweb.com/some-sharks-have-to-swim-to-survive-but-most-dont/

About the Creator

Shubham Maurya

Exploring the wild, one story at a time. Nature nerd, animal enthusiast, and world wanderer with a passion for the untamed.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.