Reflections

Looking into the world of an endangered spider monkey.

There were several moments in which I questioned my sanity when I took nothing but my filled backpack and camera with me to spend the final weeks of the year in the middle of the Panamanian jungle. Because I was a naïve college sophomore, my parents feared it was actually a secret cult that was just miraging itself as a primate rehabilitation sanctuary. While the cult theory never came to fruition, they were right that it was not everything it appeared to be.

But I was desperate. Desperate to help, to be a part of the solution, to protect wildlife. So, after four flights and one frantic trip to certify my passport, I finally arrived in the Chiriquí province of Panama. In the airport, one of the senior sanctuary interns greeted me and we drove one and a half hours to the center; our surroundings quickly went from strip malls and cement to a long and winding dirt road shrouded under the forest canopy. Arriving was a surreal experience: looking out into the estuary, meeting my twelve new roommates and coworkers, hearing the calls of the howler monkeys, and seeing the two nearby tamarinds that were currently calling a cage a home.

I was also shifting my ideas of where I lived; for the next sixteen nights, my bed would be a hammock placed between two beams located across from the “kitchen”. Favorite dishes that we cooked were fried plantains and banana pancakes--Savanna made the best pancakes (the secret ingredient was vanilla almond milk). Most of the produce in the area was reserved for the intakes: five howler monkeys, two tamarinds, one capuchin, and a spider monkey named Luna.

Even though each residing animal had their own unique personalities, Luna was different. Everyone knew it, too. Her curiosity was striking when she looked at you, and she was sharp. One December morning she noticed an intern’s CamelBak. Without skipping a beat, she used her prehensile tail to grasp and swing from the branches and walls of her cage to quickly commit the crime of grand-theft-hydration pack. While watching her, I noticed something extraordinary. Not only was she climbing and playing with its straps across her, but she had figured out how to drink from the water-dispensing tube.

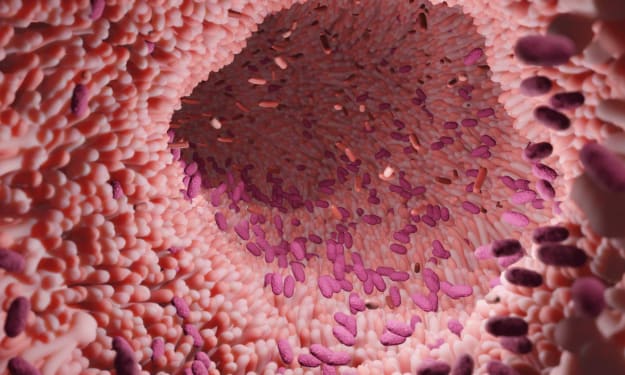

Spider monkeys are known for their smarts. Scientific studies have shown that they are the third most intelligent nonhuman primate, making them smarter than gorillas. There are seven different species of spider monkeys, and Luna was a black-faced spider monkey. Because of habitat destruction, being hunted for food, and the exotic pet trade, this species is listed as endangered. Over the past 45 years, their populations have dropped 50%.

By the time I arrived, Luna’s story had turned more into lore. No one knew for sure where she came from, but she was most likely a discarded pet, or possibly an orphan of a bushmeat kill. All of their backgrounds had the same commonality: human interference, whether direct or indirect. One howler monkey was electrocuted by a telephone pole and was the lone survivor of her family; she was blinded by the incident and would never return to the wild. The two tamarinds were displaced after being owned as pets when they were young and becoming too aggressive once they reached sexual maturity.

The exotic pet trade is a part of a thriving underground economy and second only to the weapons and drugs black market. According to the Humane Society of the United States, it is a 15-billion-dollar business in the United States alone. With the rise of the internet and Instagram, a new fuel has been added to the trade through “cute” pictures of people owning wild animals.

It can also be used as a free advertising platform for false sanctuaries. In these situations, well-meaning individuals come to these places to visit with the animals and take pictures with them. These pictures can go viral and lead more people to add it to their “bucket list”. What many animal-loving tourists don’t realize is that this industry is built on exploitation rather than conservation, and many (if not most) of these attractions are detrimental to the specific animal’s health and to their overall species’ health.

But where we were was different. We weren’t posting on social media about a 15-minute encounter with an exotic animal. We were staying there for weeks and volunteering our entire days to the care and rehabilitation of these monkeys. We were researchers, writing down data on their time in the trees and how they were interacting with any wild monkey troops nearby. We hiked five miles a day to and from Luna’s enclosure. We woke up at 4 AM to scorpions in our boots and prepared the monkeys’ specific and scientifically backed meals. We were adding to the conservation efforts of these species, not supporting their entrapment...right?

As I would later learn, this same place was referred to as the “scam sanctuary” by the locals.

There are many details that were dicey at best about my and my fellow interns’ experiences. The “research” we were doing was never coherently documented or preserved by the owners who claimed to be conservation researchers themselves. Previously released capuchins could be seen roaming the grounds looking for food or attention from us. Two dogs were also residents and would interact with the monkeys during their enrichment time--this interaction and trust of dogs could ultimately lead to their death in the wild. The primate food was not placed in sanitary containers and could easily hold bacteria. Safety did not appear to be a priority; there wasn’t a vehicle at the sanctuary to take us into town if anything were to happen, say, an unseen scorpion in the boot.

After I had left Panama, rumors surfaced that the owners had stolen the monkeys from a locally founded sanctuary. Many of us began to question how much they were actually actively working to re-wild the animals or find more permanent places for them. I learned stories of interns being forthcoming with concerns about the rehabilitation plans for the monkeys, but they were immediately shut down or berated for their comments.

And Luna, a social creature by nature, was alone. Pent up in her enclosure, she often looked for ways out and had a reputation of escaping. Her body had marks from where she would try to fit through the metal chain links.

I would be remiss to leave out that the manager was spectacular, smart, and clearly cared deeply about each person and animal at the sanctuary. The two local employees were also highly respected and adored by both interns and monkeys alike. It was higher-up where things became less clear.

The owners promised us their sincerest efforts to protect and care for their intakes while working towards an eventual release into the wild. An idyllic scenario where their future was what we all had hoped and worked for.

But that’s the thing about promises: they are too freely given out and too easily broken. In a shockingly brief Facebook post to the past and present interns, we were informed that the sanctuary had closed, and the government was now going to decide the future of the remaining monkeys. ‘Remaining’ because the several of the howlers had died due to a disease from a wild troop.

Luna was scheduled to be released into the nearby Darien rainforest.

While this had been our hope for so long, many of the interns had the same question: was she ready? And if she was, why hadn’t it been organized beforehand? The sanctuary offered tours and everyone wanted to see the rare and beautiful endangered spider monkey. How much money had she brought in? Was she simply a commodity to the center?

Our society promises us happiness through a never-ending cycle of buying products, distancing us evermore from the wild inside us. Purchasing exotic pets, swimming with dolphins, paying to see a “rehabilitating” spider monkey...they all show we yearn to be a part of this wild. But what if instead of the need to own the wild, we opened up ourselves and owned our own wildness? What if we worked to reconnect with nature rather than exploiting it? These all-too common opportunities don’t connect us to that creature’s world, its ecosystem, its wild; it takes that away. The value of nature is not from what we gain from it, but from its miraculous existence.

I am not sure if I will ever learn the ‘truth’ behind the history of our small sanctuary in the middle of the jungle. I often wonder if I helped at all, or had just simply given up my (at the time) life savings to a place that was more concerned with being well-off with money rather than the well-being of the monkeys.

But what I think about the most is Luna. When I look at this photo and I see my reflection in her eyes, I think of humankind’s love of wildness and wildlife. How our insatiable desires manifest themselves and how they can lead to destruction. The forest behind the linked metal calls out in muffled tones, and she looks to me. I wonder what she would say to me. I wonder what happened to her, where she is, and if she’s still alive. Was she ever released into the rainforest? Spider monkeys can live upwards of thirty years; how much of that time was spent where she was meant to be?

I didn't do much editing to the photo, other than bringing out some of her wrinkles and her eyes. Luna is pretty perfect the way she is.

There is irony and an oxymoron here. Wild, captured. Luna was a captive to humans after being threatened and personally impacted by us. Yet, I hope this image speaks more to the hope of a newfound connection with the wild and what the future may hold. Not only for Luna, but for humankind.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.