Hazardous Products Are Everywhere

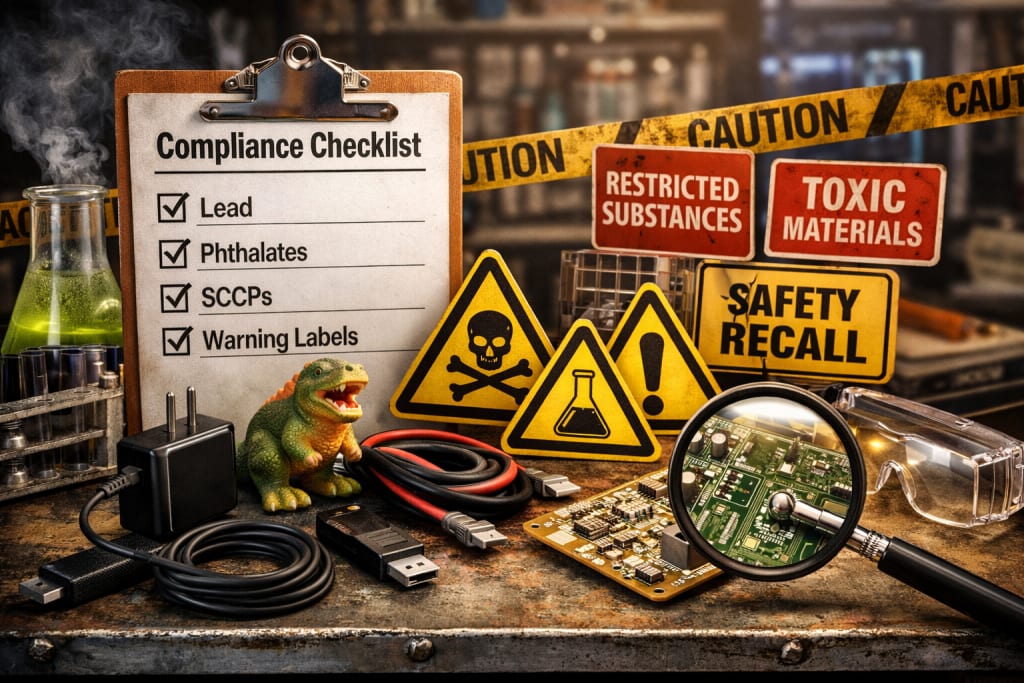

How Compliance Failures Happen (and How to Avoid Them)

Most companies don’t intend to sell hazardous products. They design something useful, source parts from reputable suppliers, and assume that if the product looks fine and works, it’s “safe.” But chemical compliance doesn’t work like that. A product can be perfectly functional and still be considered “hazardous” in a regulatory sense—because it contains restricted substances above legal limits, triggers consumer exposure risks without required warnings, or lacks the documentation needed to prove compliance during an inspection.

If you sell electronics, consumer goods, accessories, or industrial products, this topic is not theoretical. It’s market access. The most common compliance failures are predictable, preventable, and—when they go public—expensive.

What “hazardous product” really means in compliance

In everyday language, “hazardous” can mean “likely to injure someone.” In product environmental compliance, it often means something more specific:

- The product contains a restricted chemical above a legal threshold (even if the product still works).

- The product includes a banned or restricted persistent pollutant.

- The product creates consumer exposure to certain chemicals, and the required warnings or labeling are missing.

- The company cannot demonstrate compliance with credible documentation, and the product fails market surveillance scrutiny.

A single screw coating, cable jacket, ink, adhesive, seal, or solder joint can be enough to put the whole product at risk—especially when a regulator or customer tests a component you didn’t think was “important.”

The four compliance “lanes” where products become hazardous

1) RoHS-style restrictions (common in electronics)

Many hazardous-product cases start with heavy metals or restricted substances in electronic parts. Typical trouble spots include:

- Solder and metal alloys (risk for lead)

- Coatings and finishes (risk for hexavalent chromium or other restricted chemistries)

- Pigments in plastics (risk for cadmium or lead in older colorants)

- Cables and wire insulation (risk for restricted additives and legacy formulations)

The catch: even if 95% of your BOM is clean, the 5% you didn’t control can fail the whole product. And “supplier says it’s compliant” is not the same as evidence.

2) REACH-style restrictions in articles (especially plastics and soft parts)

A huge portion of product chemical risk lives in flexible plastics and “soft-touch” components. The usual suspects are plasticizers and additives used to achieve flexibility, durability, or flame resistance.

- High-risk product elements include:

- grips, gaskets, seals, soft housings

- flexible cables, strain reliefs, molded boots

- coatings, inks, labels, adhesives

These materials may look harmless, but small formulation changes can introduce restricted substances. This is one of the reasons recycled plastics and mixed feedstocks require extra care: you may not control every input.

3) POPs-style restrictions (persistent pollutants)

Persistent pollutants are chemicals that stick around in the environment and build up over time. For manufacturers, the practical takeaway is simple: certain older additive packages in polymers—especially in cables and flexible materials—can create compliance nightmares.

Where POPs risk often hides:

- cable jackets and wire insulation

- flexible housings and protective sleeves

- flame-retarded plastics

- some legacy industrial components

A company may unknowingly inherit this risk through “equivalent” materials, distributor substitutions, or older stock.

4) Warning-based frameworks (like exposure warnings)

Some rules focus less on whether a chemical is present and more on whether consumer exposure is possible and properly communicated. A product might be legal to sell if it carries the right warning and the company has done the right evaluation.

This is where many brands get tripped up:

They assume “not banned” means “no warning needed.”

They don’t assess realistic exposure routes (touch, wear, migration, handling).

They don’t keep records showing how they reached their decision.

Why hazardous-product issues keep happening

Even experienced manufacturers fall into the same traps:

- Documentation gaps

- No complete flat BOM

- No material declarations tied to each part

- Certificates that are outdated, generic, or not product-specific

- “We comply” statements without limits, test methods, or revision control

- Changes that bypass compliance

- Supplier changes resin or additive package

- Factory changes plating line or pigment source

- Procurement approves “equivalent” parts

- A distributor ships an alternate part number

- Engineering tweaks a design and introduces a new adhesive, ink, or coating

- These changes are common—and they’re exactly why compliance needs a change-control process.

- Testing that’s too narrow (or too late)

If you want the fastest risk reduction, focus here:

Cables and wire insulation

A frequent source of restricted additives and legacy formulations.

Flexible plastics (PVC-like feel, soft-touch parts)

High likelihood of plasticizers and complex additive packages.

Coatings, paints, inks, labels

Small mass, big regulatory impact—especially if pigments or curing chemistries are problematic.

Metal finishes and plating

Finishes can introduce restricted substances even when base metal is fine.

Adhesives and sealants

Often overlooked, often proprietary, sometimes high-risk.

Recycled polymers

Great sustainability story—until contamination introduces restricted chemicals.

How to prevent your product from becoming the next “hazardous product” story

Build a compliance-ready BOM (not just an engineering BOM)

Your BOM should connect each part to:

- supplier name + part number

- material type

- finish/coating (if any)

- compliance evidence (declaration, test report, material disclosure)

- revision date and who approved it

- If a part changes, the compliance status must be re-evaluated—not assumed.

- Use risk-based testing

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.