Barnard's Star b: A Frozen Super-Earth Right Next Door

Could this icy world help unlock the secrets of the galaxy?

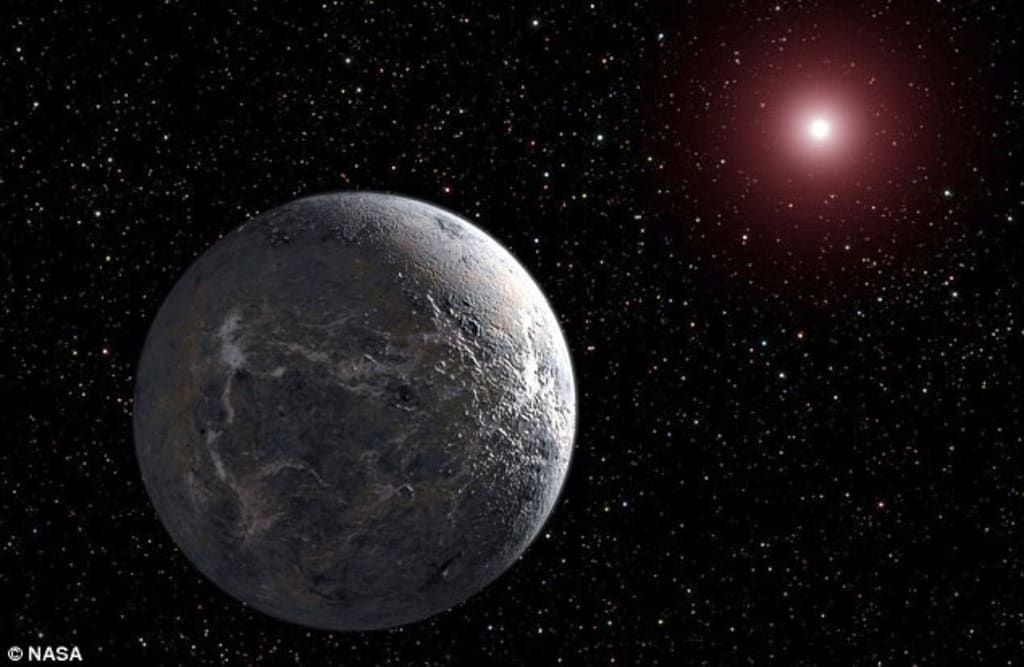

Astronomers have discovered evidence of an exoplanet orbiting Barnard’s Star, the closest single red dwarf to our Solar System, just 5.96 light-years away. The planet, named Barnard’s Star b, has a mass about 3.2 times that of Earth and completes one orbit every 233 days.

The discovery, led by Ignasi Ribas from the Institute of Space Sciences in Spain, was published in Nature. Using more than 700 observations collected over 20 years, the team employed the radial velocity method with a 99.2% certainty to detect the planet.

Although Barnard’s Star b is quite close to Earth in cosmic terms, its conditions are far from friendly. Orbiting well outside the habitable zone — at a distance five times beyond where liquid water could exist — the planet’s surface is estimated to have a frigid average temperature of -170°C, making it more of a “frozen hell” than a second Earth.

Even so, the discovery is significant. Barnard’s Star is a low-mass red dwarf, just 1/7 the mass of our Sun and emitting only 2% of its energy. These types of stars are common in the galaxy and have incredibly long lifespans, raising questions about whether other red dwarf systems might host more hospitable planets.

Currently, Barnard b is unlikely to support life as we know it. However, scientists suggest that over time, as the star cools and becomes less active, the planet’s atmosphere might stabilize, increasing its habitability — though humanity would have to wait a very, very long time to see that happen.

While the planet doesn’t transit its star from our point of view — making direct imaging difficult — researchers hope to study it further using powerful telescopes like Hubble and James Webb.

In addition to Barnard b, the team spotted signals suggesting up to three other potential exoplanets in the same system, though more data is needed for confirmation. According to researcher Alejandro Suárez Mascareño, the discovery highlights that the "neighborhood around Earth is full of small-mass planets."

Since the 1990s, over 5,700 exoplanets have been found, but only a few are within the habitable zone. While Barnard b itself might be frozen and barren, it represents a critical step toward understanding the diversity of planetary systems in the universe.

Perhaps most importantly, it reminds us that even icy worlds can hold clues about the origins of life — and that the search for our cosmic neighbors is far from over.

While Barnard’s Star b may not be the perfect candidate for life as we know it, its discovery plays a crucial role in expanding our understanding of planetary systems beyond our own. The fact that it orbits a red dwarf — the most common type of star in the Milky Way — gives astronomers insight into what the majority of planetary systems might look like in the galaxy.

In recent years, red dwarfs have become a major focus in the search for exoplanets. Their smaller size and lower brightness make it easier to detect the subtle wobbles caused by orbiting planets. However, red dwarfs also tend to be highly active in their early stages, emitting powerful solar flares that could strip atmospheres from nearby planets. This makes the study of older, quieter red dwarfs — like Barnard’s Star — even more important, as they may host planets with more stable conditions.

What makes Barnard’s Star b especially intriguing is its proximity. At just under 6 light-years away, it’s the second-closest known exoplanet to Earth, after Proxima b. This close distance makes it an ideal target for future observation. If humanity ever develops faster and more advanced spacecraft, Barnard b could one day be part of a real interstellar mission — even if just for robotic exploration.

In the meantime, astronomers are eager to learn more using the tools already available. Space telescopes like James Webb (JWST) are designed to peer deep into exoplanetary systems and potentially detect atmospheric signatures — such as water vapor, carbon dioxide, or even biosignatures like methane. Though Barnard b may not currently have an atmosphere, studying it can still teach us how planetary atmospheres are lost or evolve over time.

Some theories even speculate that Barnard b might have subsurface oceans, especially if it's geologically active. Just as Jupiter’s moon Europa has a thick icy crust hiding a liquid water ocean beneath, Barnard b might have a similar hidden layer. If so, it could be a candidate for hosting microbial life in environments shielded from the freezing surface and harsh cosmic radiation.

The broader implication of this discovery is philosophical as much as scientific: planets like Barnard b may be commonplace, not rare. The Milky Way could be teeming with rocky worlds, each at different stages of development, and some might be far more hospitable than we expect. Finding planets around stars like Barnard gives researchers valuable data points to refine models of planet formation, habitability, and even the potential longevity of planetary systems.

So, while Barnard’s Star b won’t be anyone’s dream vacation spot anytime soon — unless you enjoy -170°C and zero atmosphere — it helps lay the groundwork for a better understanding of our galactic neighborhood. Every new planet discovered brings us closer to answering one of humanity’s biggest questions: Are we alone?

And if we’re not — will the first signs of life be found on a planet just six light-years away?

Only time (and better telescopes) will tell.

About the Creator

Eleanor Grace

"Dream big.Start small.Act now."

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.