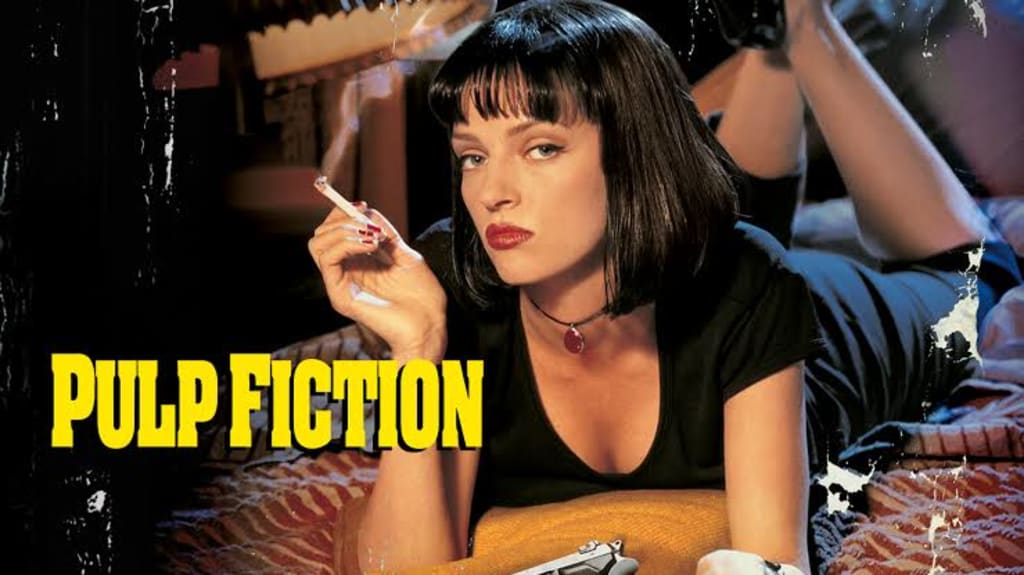

Charming Classic - “Pulp Fiction”

Levar’s Film Reviews

“I’m trying Ringo. I’m trying real hard to be the shepherd.” - Jules

At the 2014 Cannes Film Festival, Quentin Tarantino gave a press conference, in recognition of the 20th anniversary of Pulp Fiction, for which he won the Palm d'Or in '94. During the conference, Quentin was his usual candid and uniquely articulate self, directing a scathing attack on modern cinema. Specifically speaking about the practice of digital filmmaking, he stated; "cinema as I know it, has died." He was talking about the tragic abandonment of 35mm film cameras, which have historically been used to shoot movies, giving cinema a distinctive visual quality that differentiates it from other mediums. Quentin's view is that using digital cameras is a step back in the art of filmmaking and that having digital projection in cinemas, is like watching "television in public". Aside from his talent for directing, these types of unabashed opinions are partially what have led Quentin to be the force he is in Hollywood.

As a lover of great cinema, it's difficult not to have an immense respect for Quentin Tarantino, both as a filmmaker and an auteur. His encyclopedic knowledge of cinema and love for the art form, are inspiring for someone with a great passion and appreciation for the best of it. I wrote here of my views towards the director's multicultural and inclusionary aspects to his filmmaking. Growing up, watching often mature cinema (as Quentin frequently references having himself been exposed to), it was refreshing to see feature-films include racial variety in textured ways. This may seem redundant or confusing to some, others have argued that his cultural and racial awareness is shallow. My view is that including variety within films in honest ways, can never be worse than being inauthentically exclusionary.

In Pulp Fiction Tarantino perfects a signature style of directing. He continues the method set up in his first film Reservoir Dogs, by merging literary and filmic practices, dividing the story into defined chapters, but does so with a non-linear narrative. This is impactful for several reasons; it's a complex way of telling a tale, but one that leaves you wanting to keep revisiting the film, to fully grasp the experience. Simply put, it's innovative storytelling.

The first time you watch this, you feel as though you've been a part of a different kind of film experience. To divulge each, minute intricacy, or even deconstruct all of the characters and events, would literally require a book, as opposed to a blog post. This is more of a dissection of the over-arching narrative and a commemorative revisiting of what makes it outstanding.

For those who have yet to see Pulp Fiction (shame on you!), the film is divided into four main story arcs: a robbery in a diner, two gangsters making a hit, a prizefighter on the run and an evening escorting a mobster's wife. These are essentially the main stories, but each intertwine and overlap with some characters appearing in several threads.

The opening scene "The Diner" follows Tim Roth and Amanda Plummer as 'Pumpkin' and 'Honey Bunny', a romantic couple, discussing whether or not to rob the cafe they're currently dining in. This scene is cleverly used at the film's beginning and end, to bridge staggered events together. It also does well to set the tone of the film; do not presume to expect the ordinary here, because that is exactly what will not occur!

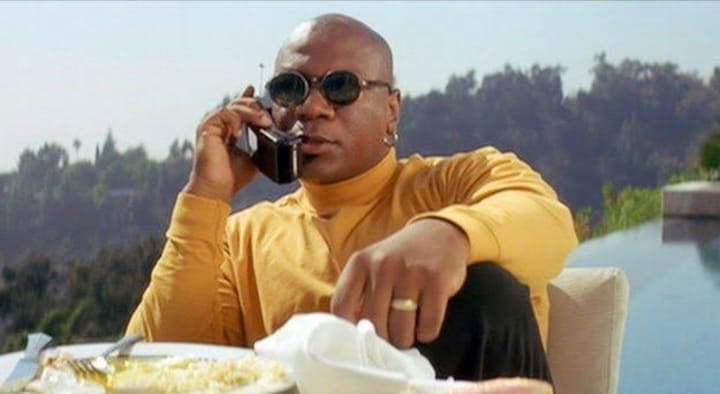

After the opening credits we're introduced to Samuel L. Jackson and John Travolta, who star as 'Jules Winnfield' and 'Vincent Vega' respectively. They're two hit men, on their way to pick up a cinematic 'MacGuffin', a package with contents that are never explained during the film. Much has been made of this package and what it signifies. For the sake of the story it's not really important, other than to know it's of clear value and significance. The collection of the package is being done on the orders of Jules' and Vincent's boss, 'Marcellus Wallace' (Ving Rhames). He's had to resort to violence by sending them to an apartment, of what appear to be postgraduate students, who've not held up their end of an illegitimate bargain. The two hitmen are the anchors of the narrative, with one or the other appearing in most of the separate story threads.

What brings this above the realm of clever and into the realm of extraordinary however, is the way in which Quentin has the characters develop as morality tales, akin to individual Aesop Fables. They do this primarily via communication with each other, in everyday ways, just as you would with colleagues. You'd be forgiven for initially thinking to yourself, 'what's going on?', as the camera follows the two men talking about burgers, foot massages, people and events, of which we have no idea about. But it makes the audience feel as though they could be a fly-on-the-wall, not in a scene with actors, but a part of actual events.

This is an interesting way to learn about characters in film. Instead of being told what type of personalities they have, via conventional cinematic tools such as action or violence, they're revealed in ways that don't feel scripted, but much more organic. Quentin makes us wait for the action and violence, it doesn't define the characters, just as violence rarely, wholly defines people in real life. As simple as this sounds, it's not a something that all directors have the ability to draw out of their actors. Woody Allen can be said to be a director with the patience to also reveal his characters in ways that are more of a norm within theatre. For this reason, a reverberating feeling of pastiche and a 'fourth wall' is established early on here.

Paralleling this are the events of Bruce Willis' ageing prizefighter, 'Butch Coolidge'. With Al Green's 'Let's Stay Together', playing during the character's introduction, the juxtapositions that work so well here are subversively established. It would be easy and formulaic to have a menacing score or some type of stereotypical song, playing during a scene involving a Faustian contract. However, these are characters who listen to the best types of love songs, while plotting dirty deeds. Butch is meeting with none other than the above mentioned, Marcellus Wallace and is being paid large sums of cash to rig the fight he is due to box in. Marcellus tells the fighter that his time has come, it's the end of his career and to bow out of the fight in the fifth round. Even when an envelope containing bundles of cash is passed over to Butch, you get the strong sense that it's Marcellus, who is getting the better end of the bargain. This sense of the just and unjust and equilibrium, are at the heart of Butch Coolidge's tale. Beginning with a scene stealing moment from Christopher Walken as an officer who establishes Butch's past, we learn that a gold watch, passed down through four generations of Coolidge men, all of whom served as soldiers in war, becomes a moral compass for the character.

Butch's story sits neatly in the middle of the film, yet underscores the overall theme of redemption. The key point is that Butch, who's paid to cheat in a fight, doesn't do so and is now willing to kill in order to get away. The gold watch, Butch's most prized possession, is of such significance, he risks his life to recover it, being the second person in the film, not to hold up his end of a Marcellus Wallace agreement. But now with the opportunity to rid himself of his antagonist and not killing him, finds himself nullifying the Faustian bargain he'd previously signed up to.

Ironic fortuitousness is evident here and present throughout Pulp Fiction. It also surfaces in subsequent chapters; 'Vincent Vega and Marcellus Wallace's wife', and 'The Bonnie Situation', but always in fresh and engaging ways.

Tasked with escorting Mia Wallace (Uma Thurman) to dinner for an evening, Vincent Vega must mind his somewhat unrefined and addictive tendencies to be civil, polite and gentlemanly towards the wife of a man he knows has men maimed and killed on a whim. Mia is young, retro and has a playfulness that can leave men unsure whether it falls into the category of friendliness or flirtatiousness. So for Vincent, whose primary role of the evening is to escort and "take care of" this lady, he finds himself in the pinnacle of bad scenarios when she ends up mistaking a bag of heroin for a bag of cocaine, with near fatal consequences. As we know however, Quentin Tarantino adds a wealth of development to his characters, establishing relationships with supporting characters of whom we are unaware will become crucial to later events. Here this takes place with none other than Vince's drug dealer, Lance (Eric Stoltz). Vincent turns to him in his time of need to save both Mia's (and invariably his own) life. The irony being the drugs came close to killing Mia, but the drug dealer is the saviour of the day.

So the importance of relationships become more and more apparent with each scene and furthermore the grounding that comes from the supporting characters, highlights why Tarantino's fantastical set of events never feel completely implausible. It's a world where you feel the main characters are a part of it, not steering it. In "The Bonnie Situation" we're introduced to 'The Wolf' (Harvey Keitel) who is the go to man to clean up messy situations of an untoward nature. After Vincent accidentally kills an informant in the back of Jules' car, they need a place to stash the car out of broad daylight and clean up the mess, both figuratively and literally. Jules calls 'Jimmy' (possibly Tarantino's best acted cameo to date) and parks in his garage. The problem however is that they have a short window before Bonnie, Jimmy's nurse wife, comes home from her night shift. "The Bonnie Situation" in many ways is used as a chapter to underline Jules' recent, 'divine intervention' desire, to leave his occupation as a hitman and this world of unpredictability and chaos. After The Wolf comes, cleans up and solves yet another Vincent oriented problem, the two hitmen find themselves seated and having breakfast in the very diner that Honey Bunny and Pumpkin had decided to rob at the beginning of the film.

Nowhere is fortuitous irony more present in the film than in this last scene, which highlights the brilliance of Pulp Fiction as a complete piece.

After deciding not only to steal from the cash register but to collect all of the valuables, purses and wallets from the many morning diners, Pumpkin approaches Jules with wallet aloft and other hand clutching a pistol. Jules uses this encounter as a time for self reflection, to be reflexive about himself as a man and his aimless life as a hired killer. Unravelling his usage of the biblical passage Ezekiel 25:17, which he previously used as a montage before 'bustin' a cap in a motherfucker's ass', he now realises that this is the opportunity to buy his way out of a life of death and into a true life of righteousness.

Quentin uses this as a means to reinforce the fact that criminality is ultimately devoid of gloss. As interesting as the majority of his criminal characters are, none escape their illegitmate and/or iniquitous passtimes without due justice. The time spent watching this film, enduring its language, being immersed in its occasionally uncomfortble mix of brutality and permeating wit, is all flagged and flanked by a scene that says; none of this is good, but that doesn't at all mean it cannot be brilliant.

Watch the Trailer here: Pulp Fiction Trailer

About the Creator

Lev. Life. Style

I’m fascinated by culture’s ability to shape thought and behaviour. I value creativity as a means of aiding wellbeing and growth. Film, analysis, travel and meaningful discussion, are personal passions that I’m grateful to share.

Lev

Comments (1)

Quentin's take on digital filmmaking is bold. I get his love for 35mm, but digital has its perks too. And his views on inclusion in films are thought-provoking. Do you think his style in Pulp Fiction could be replicated today, or has the industry changed too much? Also, how do you feel about his criticism of digital projection? Is it really like watching TV in public?