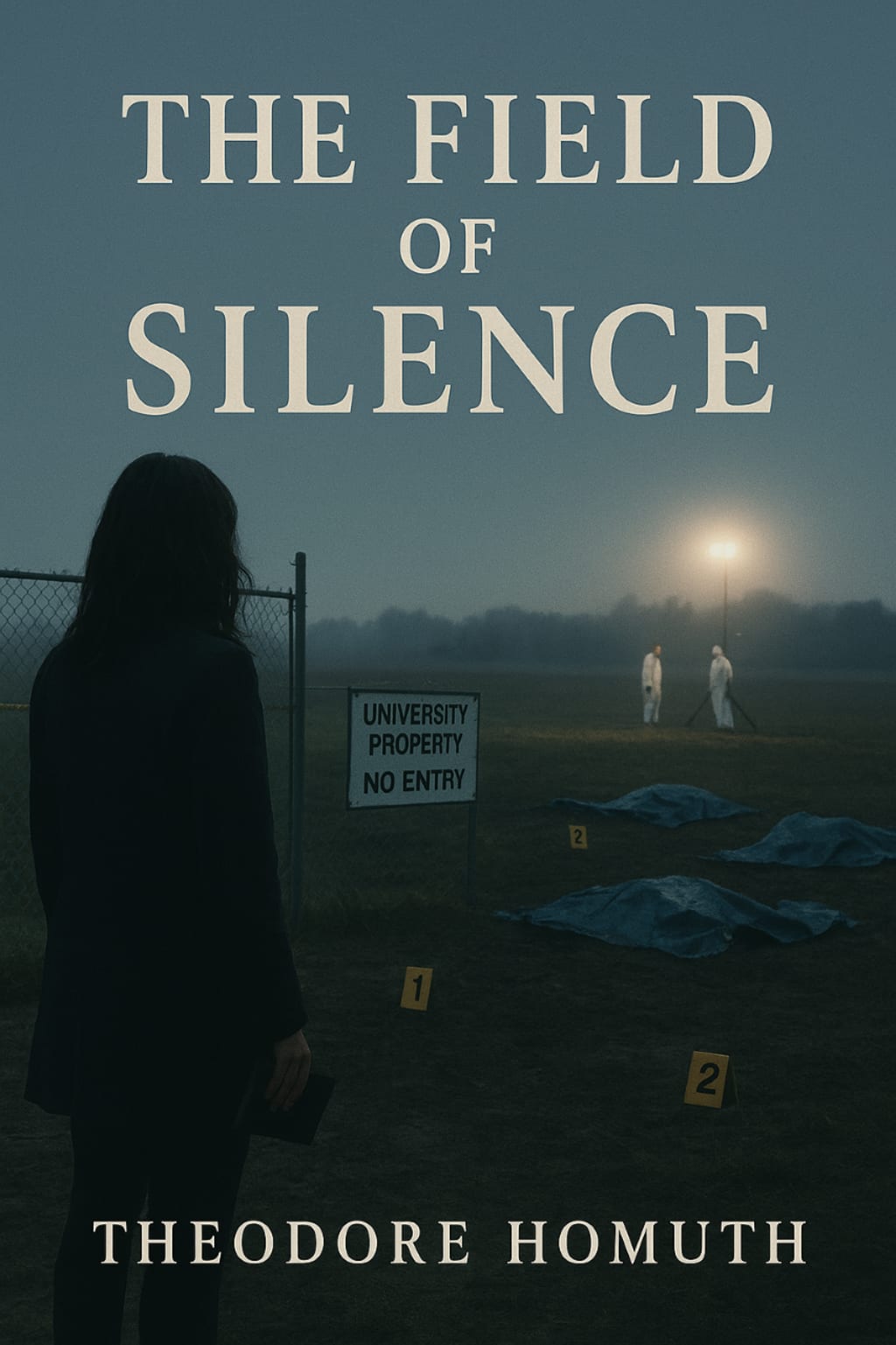

The Field of Silence

Based on True Events (AI Cover)

The Field of Silence

(Based on true events)

The first thing they tell you when you visit the Kell Site is don’t step off the marked path.

The second is don’t ask where the bodies come from.

Officially, it’s called the Kell Forensic Anthropology Research Field, a patch of fenced farmland just outside Woodstock, Ontario, where donated human remains are studied as they decompose in controlled conditions. Unofficially, among law enforcement and the university interns who work there, it’s called The Field of Silence. The nickname started as a joke, but by the end of 2022, no one was laughing anymore.

I. The Donation Program

On paper, the program was transparent. Donors could sign a form through the Ontario Human Research Authority, consenting for their bodies to be used “in the advancement of forensic and environmental sciences.” It sounded noble. Clean. Scientific.

But in early 2023, local journalist Erin Voss began looking into a set of leaked internal memos from the University of Western Ontario’s Department of Forensic Science. They referenced something called “Batch 47–Unidentified.” The wording suggested these weren’t voluntary donors.

Voss filed a freedom-of-information request. It was denied.

That’s when she drove out to Woodstock and stood at the edge of the Kell Site for the first time — a half-acre of mud, steel fencing, and quiet wind moving through the sumac. She expected white lab tents and students in hazmat suits. Instead, she found a gravel road, two cameras on poles, and a hand-painted sign:

NO ENTRY WITHOUT AUTHORIZATION — PROPERTY OF THE UNIVERSITY.

A month later, she received an anonymous message through her encrypted email tip line:

“You’re asking about Batch 47. I was there. You should talk to Lena Harrow before she disappears.”

II. The Intern

According to school records, Lena Harrow was a graduate assistant from Guelph, 26 years old, specializing in forensic entomology — the study of insects on decomposing bodies. Her thesis proposal was approved in late 2021. She started fieldwork at Kell in May 2022.

Three months later, her research logs stopped.

In interviews with her classmates, Voss learned that Lena was methodical and a bit of a perfectionist. “She’d stay out there after dark,” one student recalled. “Counting blowfly larvae by flashlight.”

Her supervisor, Dr. Robert Kell, founder of the site, described her as “dedicated, but emotionally volatile.”

When Voss pressed for details, he ended the call.

III. The Logbook

In October 2023, a former groundskeeper from the site — speaking under condition of anonymity — handed Voss a small black field notebook wrapped in a ziplock bag. On the cover:

Harrow – Batch 47.

The entries began like any research log: temperature, humidity, rate of insect activity, soil acidity. The tone was clinical, almost detached — until Day 18.

Day 18 – Subject 47A. New bruising visible under right clavicle. Purple-green patterning not consistent with postmortem artifact. No pooling. Possible perimortem trauma?

Day 19 – Notified Dr. Kell. Told me to adjust pH data, disregard discoloration. “Old tissue artifacts,” he said. Doesn’t look old.

Day 22 – Early morning. Site camera offline. Heard sound — faint gasping? Checked logs; no wildlife entry. Don’t know what I heard.

After Day 22, her handwriting shifted — hurried, jagged.

Day 25 – Soil sample shows residual traces of a sedative compound. Not typical embalming chemicals. Tested twice. Confirms benzodiazepine derivatives. These bodies weren’t dead when they arrived.

IV. The Silence

When Voss cross-referenced hospital records and coroner’s reports, she found a disturbing overlap: several unclaimed bodies listed as transferred to “university-affiliated research facilities” had been previously admitted to Fairview Care Centre, a privately operated long-term care home outside Ingersoll.

Four of those deaths occurred within the same 48-hour period.

All were marked “DNR – natural causes.”

None were autopsied.

Fairview’s director declined comment. The university denied any connection, citing “confidential research partnerships.”

But someone at the care home was talking. A nurse, who’d quit two months prior, told Voss off-record that late at night, “transport vans with blacked-out windows” would arrive at the rear loading bay. The drivers wore university badges. No morgue paperwork was visible.

“They weren’t picking up donors,” she said. “They were picking up patients.”

V. The Final Email

Through a subpoena filed later by Voss’s paper, a copy of Lena Harrow’s final university email was obtained. Sent July 18, 2022, at 11:42 PM to Dr. Kell, subject line: “This isn’t research anymore.”

“Robert,

I’ve tested three samples now. Two show active sedatives. There’s no chance these people were clinically dead when processed. We need to notify the OPP immediately. If the university buries this, I’ll go to the media myself.

—L.”

There was no reply.

Forty-eight hours later, she was reported missing by her roommate.

VI. The Night Watchman

Security footage from the Kell Site during that same week was “accidentally corrupted,” according to university IT logs. Only a single frame survived: 1:26 a.m., July 19. A figure, female, wearing a lab coat, walking between tarp-covered research plots.

At the far edge of the image, a man stands beside a white transport van. His face is turned away from the camera.

That van, according to vehicle registry, was leased by the university’s Department of Applied Human Research.

VII. The Recovery

Six months later, a spring thaw exposed what appeared to be human remains in a drainage culvert bordering the site’s western fence line. Local authorities ruled them “inconclusive due to environmental degradation.”

The coroner’s report described “partial skeletal remains of a young adult female.” No DNA record was publicly released.

Unofficially, two forensic students told Voss that the recovered bones matched the dimensions listed in Harrow’s student medical file.

The report was quietly sealed under provincial research exemption law.

VIII. The Interview

In March 2024, Voss met Dr. Kell in person. They spoke in his office at Western — an orderly room filled with academic plaques and sealed specimen jars. He was calm, articulate, and entirely unruffled.

Voss: “Did you know about the sedative compounds found in the Batch 47 samples?”

Kell: “Miss Voss, decay produces strange chemistry. It’s a messy process.”

Voss: “Lena Harrow believed those subjects were alive when they arrived.”

Kell: “Lena was under stress. The field can warp perception. You see what you expect to see.”

Voss: “And what about the missing footage? The van?”

Kell (smiling): “Curiosity can be dangerous in our line of work. Sometimes it kills the cat before the autopsy.”

After that meeting, he refused all further contact. Three weeks later, he retired.

IX. The Leak

In August 2024, an anonymous FTP link was sent to multiple news outlets across Canada. The folder contained nearly 4GB of internal documents: transfer records, donor logs, and correspondence between Kell and Fairview administrators.

One file stood out — labeled “Project Lumen: Phase I.”

The proposal described a joint study between the university and a private biotech subsidiary seeking to “observe neural activity during end-stage consciousness.” The document referenced “human subjects in controlled terminal decline” and requested access to “nonresponsive but vital participants.”

Handwritten in the margin of one page:

Field integration to commence June 2022.

—R.K.

X. The Cover-Up

The university issued a statement calling the documents “fraudulent fabrications.” Fairview Care Centre shut down “for renovations.” No criminal charges were ever filed.

Voss’s story ran in The Chronicle under the headline:

“THE FIELD OF SILENCE: What Really Happened at Ontario’s Only Body Farm.”

Within a week, she received three separate legal threats and one anonymous envelope containing a single Polaroid photo.

The image showed a stretch of muddy ground at night, illuminated by a flashlight beam.

In the center of the frame: a pair of latex gloves and a torn research badge.

The name was still visible: HARROW.

XI. The Aftermath

The Kell Site was decommissioned in early 2025. The university bulldozed the fencing, filled the plots with gravel, and planted wild grass. Officially, it’s now a “wildlife restoration reserve.”

But satellite imagery taken six months later shows something strange — an irregular patch of darker soil in the center of the field, roughly the size of a shallow grave.

Some nights, farmers nearby claim they hear alarms — faint beeping from underground sensors that should no longer exist. Others say the cameras on the old fence posts still turn toward them when they pass by.

No one goes near the site after dark.

XII. The Final Note

When The Chronicle published its follow-up piece, the editors added a brief addendum at the end — a quote from Lena Harrow’s recovered notebook, scrawled across the final page in uneven ink:

“Science tells us death is the end of consciousness.

About the Creator

Theodore Homuth

Exploring the human mind through stories of addiction, recovery, and the quiet places in between.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.