Mrs. Sherlock Holmes and the Murder of Ruth Creuger

The woman who solved the case the NYPD could not

On February 13, 1917, seventeen-year-old Ruth Creuger, a recent high school graduate, told her sister Christine that she had some errands around their Harlem neighborhood in New York. Ruth left the house at 11 in the morning but never returned.

Christine’s worry grew, and she called their older sister Helen at work. Helen postulated that Ruth had gone ice skating since one of her errands included getting her skates sharpened. Despite offering her sister reassurances, Helen left work early to retrace her sister’s steps.

Most of the businesses Ruth had visited that day had already closed when Helen reached them, and Ruth wasn’t at the ice rink. Helen raced home, hoping that she and Ruth had missed each other, but Ruth still hadn’t made it home. Helen called her father’s business partner, Mr. Brown, who sent a telegram to the girls’ parents in Boston, where they were vacationing: Come home quickly. Ruth has disappeared.

Mr. Brown arrived at the Creuger’s Harlem apartment and tried to reassure the sisters before phoning the police. Early the following morning, Henry Creuger and his wife returned home to find Ruth still missing in the frigid New York winter.

Henry Creuger, a prominent business executive, angered that the police hadn’t begun searching for his missing daughter yet, contacted the newspapers. Two days after Ruth’s disappearance, her picture appeared on the front page of the New York Evening World amid news of Germany and the impending first World War.

When the mail arrived, the family searched for a ransom note, but to their relief and terror, they found none. Frustrated with the police’s inaction, Henry Creuger hired a private detective and gave him the layout of Ruth’s plans for the day she went missing: to the bank to deposit a check, the motorcycle shop for ice skate repair, and the stationery shop.

Two days after Ruth vanished, a pair of detectives arrived at the Creuger’s apartment. Detectives Lagarenne and McGee were a shoo-in as body doubles for Laurell and Hardy.

While the detectives questioned the family, Helen investigated on her own. She went to all the places she knew Ruth frequented and discovered a lead the police didn’t yet know. The man at the motorcycle shop said Ruth headed east after picking up her skates.

The following morning, Mr. Creuger, accompanied by his business partner, Mr. Brown, went to the Fourth Branch Detective House and demanded that police search every square inch of his Harlem neighborhood for his missing daughter.

Detectives Lagarenne and McGee assured the troubled family that their investigation was well underway and their most significant lead was the motorcycle shop. Police dug into the background of its owner, Alfredo Cocchi, as he was the last person to see Ruth. However, Mr. Cocchi was clean, and the police had no reason to suspect him of wrongdoing.

The detective then began questioning Mr. Creuger about his missing daughter’s character. They had a witness placing Ruth and an older man in a cab heading to the subway. Was it possible that Ruth had eloped?

Mr. Cruger, angered by the detectives’ line of questioning, assured them that his daughter hadn’t run off with a man. He was sure his daughter was a victim of something foul.

Before Mr. Crueger and his business partner, Mr. Brown, left, the detective cautioned them to say nothing to anyone, especially the press, about the cab, as they hadn’t yet followed up on it. However, the police’s investigation insulted Henry Creuger. When the press called the following day, Creuger mentioned the cab driver to the reporter.

The following morning, Maria Cocchi visited the Fourth Branch Detective House to report her husband, Alfredo Cocchi, missing. Maria was surprised to learn that the police had searched her husband’s motorcycle shop for the missing Ruth Creuger. Alfredo Cocchi hadn’t mentioned it to his wife, something Maria and the police found suspicious.

Friends and family lauded the character of Alfredo Cocchi. They were adamant that he had nothing to do with Ruth’s disappearance and that he had fled to avoid persecution over his Italian birth.

Unable to locate Cocchi, the police searched for Ruth’s wristwatch and class ring at local pawn shops but came up empty-handed. By Sunday, the church Ruth attended had sprung into action, distributing thousands of flyers citywide with Ruth’s photo. Several leads followed, but none led to Ruth.

Several days later, reporters located the cab driver who claimed to have taken Ruth to the subway with an older man, but he told a much different story than was initially thought. The lead fell apart, leaving investigators with nothing.

A week after her disappearance, Detectives Lagarenne and McGee felt the investigation for Ruth was pointless and tried to convince Police Commissioner Woods that Ruth had run away. However, Woods, having once been employed as a reporter, knew this type of story could blow up in their faces and instead placed 50 full-time detectives on Ruth’s case, following up on nearly 700 tips.

Two weeks after Ruth went missing, the police spoke to Miss Shelly, a telephone operator in Ruth’s building, who reported that Ruth had made two calls the day she disappeared. The first was at 1:07 p.m. to her friend Roseline and the second at 1:09 p.m. to a fraternity house at Columbia University. However, neither Roseline nor her mother remembered receiving a call from Ruth.

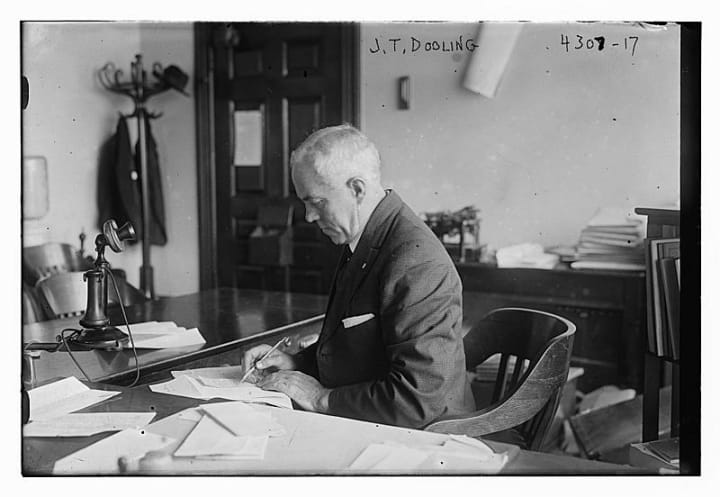

John T. Dooling, the new District Attorney, contacted Roseline’s mother, who gave him a list of boys’ names Ruth knew. One name stood out; Seymour Many. Ruth and Many were childhood friends and kept in touch through letters. Many claimed that Ruth had told him of a young man she’d met while skating who attended Columbia. However, Ruth’s father hadn’t approved because a mutual acquaintance hadn’t introduced the pair. The young man’s name was Richard Butler. When pressed to bring in Ruth’s letter, Seymour Manny said he had destroyed it, as he did with all letters he received from young women.

Dooling interviewed Richard Butler the following day, who provided a list of his activities the day Ruth went missing, down to 15-minute increments. While it appeared Butler had an ironclad alibi, his rounds about the city brought him blocks of where Ruth had been the day of her disappearance. Still, Dooling had no evidence to hold Butler.

Seventeen days after Ruth disappeared, Henry Creuger held a press conference that he had obtained a new lawyer to help search for this daughter. A woman standing apart from the huddled family, dressed in mourning black, took to the podium, introducing herself as Grace Humiston, who set some ground rules. Any correspondence or leads from the press were to go through her, not the family.

In 1903, Mary Grace Quackenbos was a law student at New York University because the more prestigious Columbia didn’t admit women. So driven was Grace that she completed her three-year law degree in two and was one of twelve women in her graduating class. In 1905, Grace passed the New York Bar and began her career as an attorney, a position she shared with only 1,000 other women in the United States.

During her career, Grace’s clients consisted mainly of poor immigrants who spoke little English and were illiterate. She also hired as many women as possible to assist her in her practice.

By June, four months after Ruth went missing, Grace had dived deep into the investigation, but leads had all but dried up, yet Grace was sure that Cocchi’s motorcycle shop held the key to finding Ruth. She sincerely believed that police corruption was involved. She just had to prove it.

Grace brought in a private detective and good friend, Julius Kron, to aid her in her investigation. They hatched a plan; Grace would look into Ruth, and Kron would dig into Cocchi’s past.

Immediately, Grace found herself at Cocchi’s motorcycle shop. Neighbors reported Cocchi’s strange behavior; the day after Ruth Crueger went missing, Cocchi closed his shop for three days and fired the boy who assisted him.

Grace tracked down the boy, names Herbert. She asked him to draw a map of Cocchi’s shop. As Herbert drew, he spoke of the last time he saw Cocchi.

Herbert arrived at the shop like he always did, but the shop was closed. Surprised by this, the boy went to the cellar and found Cocchi. He fired the boy on the spot. The following day, Herbert spied Cocchi’s name in the paper and ran to the shop. Cocchi demanded that the boy buy two more newspapers. When Herbert returned, Cocchi took the papers and locked himself in the cellar.

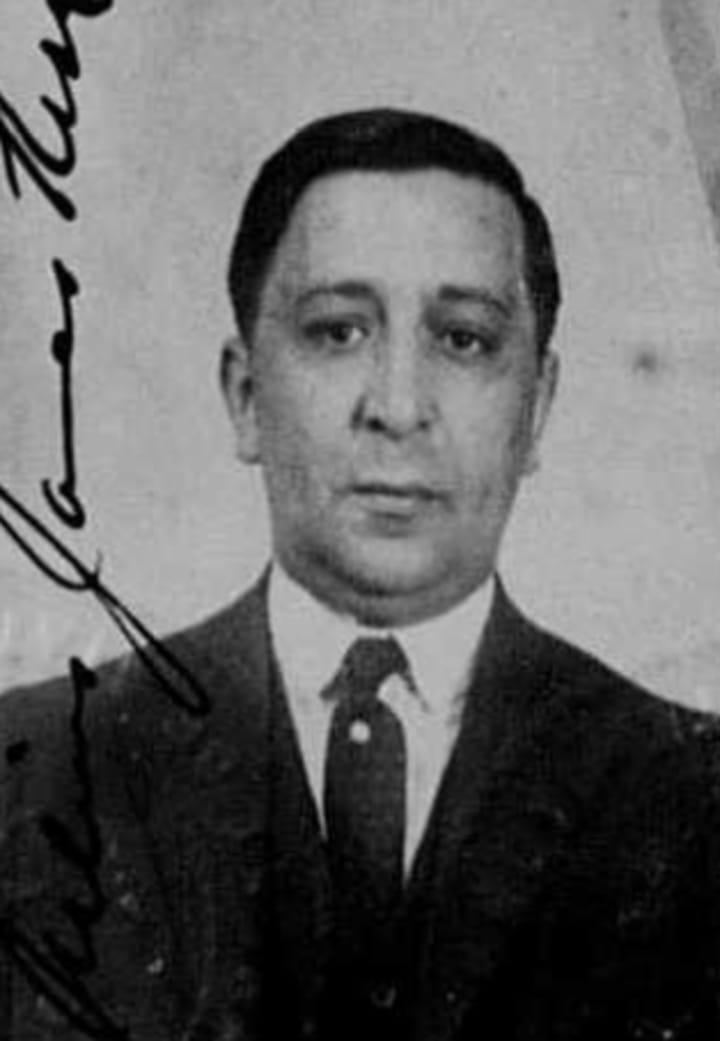

After she visited with Herbert, Grace discovered a mob of reporters gathered outside her office. Italian authorities had found Alfred Cocchi’s in Bologna, Italy. Cocchi maintained he knew nothing of Ruth Creuger and that he had left New York to evade his harpy of a wife, not the law. The timing of the two incidents was nothing more than a coincidence.

A few days later, Police Commissioner Woods called Grace to tell her that investigators had found Ruth in Mount Vernon, living with a man. Mr. Creuger and Grace hurried to the location only to find that the woman was not Ruth, much as Grace had feared.

Kron phoned Grace later that night and informed her that Cocchi had a history of inappropriate behavior with young women and girls. Rumors circulated that the shop’s basement was a hub for criminal activity. An old landlord of Cocchi’s claimed he brought girls to the shop and sold them for a few hours to the highest bidder. Kron had discovered several sexual assault complaints that went nowhere because the families wanted to avoid scandal. However, Commissioner Woods had received one such sexual assault report. Whether this assault didn’t make it into Cocchi’s file or the police disregarded, it is unknown. When police first questioned Cocchi, he had deep scratches on his arm and face, which he claimed were from a row with his wife, Maria.

As Grace looked over her file on Cocchi, she commented the police had let a predator go free. Kron assured her they would see him imprisoned, but Grace knew they needed more evidence. They needed to get into the cellar. Grace hatched a plan.

She placed Kron in the garage as a motorcycle repairman, something he knew nothing about, which made him sweat. He’d been undercover many times, but not like that. But Maria Cocchi was desperate for help in the shop and hired Kron on the spot. However, she shut him down whenever he got close to the cellar. If Kron ever needed anything kept down there, Maria Cocchi retrieved it herself.

Grace tried another angle. While Kron worked the shop angle, Grace hired a female detective to rent a room from Maria Cocchi to keep tabs on her at home.

However, Kron’s luck changed five days after taking the job in the motorcycle shop. Maria Cocchi allowed Kron entrance to the cellar when he claimed he needed to weld something. Maria let him go into the basement alone while she watched the shop. Kron made a quick mental note of the cellar’s layout; workbench along one wall, rags on the floor, a large tool chest in the corner, and the powerful odor of motor oil. Korn scanned for anything that seemed out of place but could find nothing amiss. Yet, his exploration of the cellar roused Maria’s suspicions, and she kicked him out of the store.

That same week, an inmate at The Tombs in Manhattan named Stephen Smith claimed Alfred Cocchi had paid him to haul away a large mound of dirt from the cellar. With this testimony, Grace tried to gain a search warrant for the basement, but the judge denied it.

Disheartened but determined, Kron snooped outside the shop when he spotted a coal chute leading to the cellar from street level. Since the pipe wasn’t technically on the Cocchi’s property, Kron shimmied down it and found a door at the bottom covered in freshly dug earth. Kron ordered a digging crew and lights.

As the crew worked, they removed the door covering a six-foot by six-foot hole that blasted through the concrete foundation. They continued digging and found a series of heavy rocks hiding large metal signs identical to those in the motorcycle shop, along with a newspaper dated February 16th, proving the hole was fresh. With this information, Grace returned to the judge and demanded a new warrant to recheck the cellar. Meanwhile, Maria Cocchi hired a lawyer to stop Grace, which had her running back and forth between the court and the shop while workers stood around, waiting to get back to digging.

Eventually, the city demanded Grace leave Cocchi’s shop, and Deputy Police Commissioner Scull released a statement that there was no connection between Alfredo Cocchi and Ruth Creuger’s disappearance. “There is no such thing as abduction,” Scull told the press. “No one has ever disappeared in such a manner in New York,” agreed Commissioner Cooper.

Not long after, The New York Times reported that 1,000 to 1,500 girls disappeared annually from the city. Concerning those numbers, Ruth Creuger’s disappearance wasn’t remarkable. Of the missing, around 80% were recovered, lowering the number to about 200–300 per year.

At this time, fears of a white slavery ring circulated, giving rise to the Mann Act, which made it a felony to transport sex workers across state lines. The hope was to deter would-be kidnappers from luring vulnerable young women into sex work.

Yet, the Crueger family was adamant that Ruth hadn’t run off. Something nefarious had happened to their daughter.

With one day left on her warrant, Grace threw a Hail Marry. She would hire a building inspector to survey the cellar. No judge could block an inspector. An inspector would know if there was some structural change to the area, and then they would know where to dig, hopefully extending the warrant.

The following day, the building inspector arrived, and Grace ushered everyone into the basement. Kron had noticed Mrs. Cocchi’s absence from the area as she watched their movements hawk-like from the shop. Grace informed Kron that Mrs. Cocchi had sold the shop to an auction house, and that she had purchased the building that morning. They could dig wherever they liked for as long as they wanted. But that wouldn’t be necessary.

Immediately, the inspector honed on a section of the cellar’s floor. Grace ordered that the workers dig there. Later that day, workers cradled Ruth Creguer’s remains in a cardboard box, lifting her from Cocchi’s basement for the first time in four months. Along with Ruth, Grace found her watch and ice skates.

When news came to Commissioner Woods that Ruth’s skeletal remains had been discovered in Cocchi’s basement, he sent a cable to Italy telling authorities to ‘Hold Cocchi.’

While the Italian government refused to extradite Cocchi, he stood trial for murder on his home soil for the death of Ruth Creuger.

New York Mayor John P. Mitchell wrote a letter to the Creuger family defending the police investigation and Commissioner Woods. One can imagine how that letter went over with Mr. Creuger.

Ruth’s family laid her to rest in Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York, on June 18, 1917. The funeral was a private affair attended by Ruth's family and Grace Humiston.

Police Commissioner Woods recommended Mayor Mitchel appoint a Commissioner of Accounts to investigate the failure of the police in locating Ruth Crueger. Mayor Mitchell chose Leonard M. Wallstein to head the commission. Wallenstein was accountable to no one but the truth. Previously, he had investigated the city’s coroners and discovered that around 50% were not licensed doctors but were milkmen, plumbers, and musicians.

As the inquest began, Henry Creuger wrote a letter to the Mayor that stated:

“The work of the department has been marked by great stupidity, if not inspired by ulterior motives. They refused to send out a general alarm until the lapse of twenty-four hours, and they said Cocchi was a reputable businessman.” Henry Creuger called the department out on their brutality in trying to tarnish Ruth’s character igloo of locating her. Instead, “[t]he much boasted efficiency of the Police Department was proved to be a hollow mockery by the persistent work of the woman.” Many men of the time would rather have been compared to a dog than say a woman had overshadowed their deeds. Creuger called for the removal of Commissioner Woods and said that any investigation “by the present Commissioner would not be worth the paper they report was written on.”

During the investigation into police misconduct, Maria Cocchi produced a ‘get out of jail free’ card given to Alfred Cocchi by Baily Eynon, a motorcycle cop. While these types of cards were not uncommon, Cocchi’s card stood out by what Eynon had written on the back: Take care of Alfred Cocchi. He’s OK. Billy Eynon.

Maria Cocchi testified police were always at the motorcycle shop, speaking in whispers to her husband. It was discovered that Cocchi and several officers ran a grafting scam, fixing tickets for sizeable sums of money. Here, the officer who’d written the citation and the fixer, Cocchi, split the money. In return for his service, the officers made complaints against Cocchi disappear, such as the sexual assault reported years earlier. The police also made a half-hearted search of Cocchi’s basement at the outset of the Ruth Creuger investigation.

Back in Italy, Alfred Cocchi was tried twice for the murder of Ruth and found guilty. On October 29, 1920, he was sentenced to 27 years.

Sources

Library of Congress: Research Guides. ‘Ruth Cruger Murder: Topics in Chronicling America.’ https://guides.loc.gov/chronicling-america-ruth-cruger-murder

Ricca, Bradm (2017). Mrs. Sherlock Holmes: The True Story of New York City’s Greatest Female Detective and the 1917 Missing Girl Case That Captivated a Nation. St. Martin’s Press.

About the Creator

Cynthia Varady

Award-winning writer and creator of the Pandemonium Mystery series. Lover of fairy tales and mythology. Short stories; book chapters; true crime. She/Her.

Comments (1)

This story is so sad. Must've been terrifying for the family when Ruth went missing.