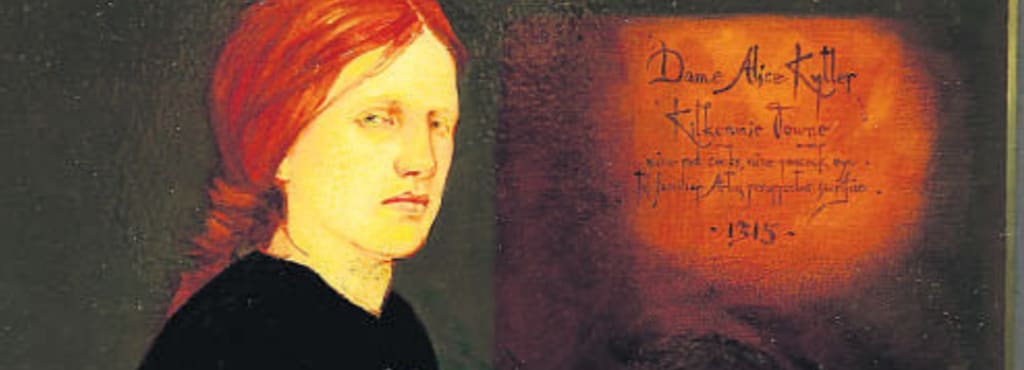

Alice Kyteler: Ireland’s First Witch Trial and the Origins of European Witchcraft Persecution

She most certainly wasn't a real magical witch, but Alice Kyteler apparently had husbands who died mysteriously...

In 1324, long before the infamous witch trials of Salem or Bamberg, a wealthy Irish noblewoman named Alice Kyteler became the central figure in one of Europe’s earliest recorded witchcraft trials. Her story is a revealing look at medieval attitudes toward power, gender, and fear of the occult.

A Woman of Wealth and Influence

Alice lived in Kilkenny, Ireland, during the late 13th and early 14th centuries. She came from a well-off family and enhanced her position by marrying four wealthy men in succession. Each of her husbands died under suspicious circumstances, leaving Alice with considerable wealth and land.

Her ability to accumulate power — especially as a woman — stirred resentment, especially among her stepchildren (who she apparently screwed out of inheritance money) and other rivals. They accused her of using sorcery and manipulation to control her husbands and take their fortunes.

The 1324 Accusations

That year, Alice faced formal charges of heresy and witchcraft. Her chief accuser was Richard de Ledrede, the Bishop of Ossory, who was determined to make an example out of her. The accusations included:

- Offering sacrifices to demons

- Brewing potions to harm or enchant others

- Holding secret nocturnal rituals

- Practicing astral projection or flight

The case became a media spectacle of its day, with powerful religious and social undertones. It was one of the earliest times a European court officially tied heresy to witchcraft, a connection that would later define centuries of witch hunts.

The Dark Side of “Witches’ Potions”

The trial touched on fears that would define witch lore for generations—especially the use of potions to control minds and bodies. Folklore and historical records describe various kinds of so-called "witches' brews," often made with deadly or hallucinogenic plants:

Love or Obsession Potions: Using plants like mandrake or belladonna, these were said to cause infatuation or emotional control — though at the cost of the victim’s free will.

Flying Ointments: Applied to the skin or consumed, these concoctions used henbane, belladonna, and other tropane alkaloid plants to cause hallucinations or “out-of-body” experiences.

Death Potions: With ingredients like arsenic or wolfsbane, these were meant to kill or paralyze.

Possession or Binding Brews: Said to trap a soul, bind a will, or sedate a victim.

Forgetfulness Potions: Believed to wipe memories, hide crimes, or make victims pliable.

Most of these so-called recipes were part folklore, part pharmacology, and part hysteria—based more on fear than science.

Escape and Aftermath

Alice Kyteler never stood trial. She fled — likely to England — and disappeared from the historical record. Her servant, Petronilla de Meath, was not so lucky. After being tortured, she confessed to aiding Alice in her alleged rituals and was burned at the stake. Petronilla became the first person executed for witchcraft in Ireland.

Legacy

Alice’s case set a precedent. It marked a shift from viewing witchcraft as superstition to treating it as a form of heresy — a crime against the church. That framework would be used for centuries to justify torture, executions, and mass hysteria across Europe.

Her trial wasn't just about magic — it was about power, control, and the fear of women who stepped outside traditional roles.

Alice Kyteler’s story lasts not because of definitive proof of witchcraft (there is none), but because it exposes the fragile boundary between law, belief, and misogyny in medieval Europe. Her case helped establish a pattern: accusations fueled by personal grievances, sanctioned by religious authority, and exacerbated through fear. It set the tone for future inquisitions where wealth, independence, or mere eccentricity could mark someone for persecution.

In many ways, Alice was a scapegoat for a society struggling with instability, religious tension, and shifting gender roles. Her escape may have saved her life, but the flames that consumed Petronilla de Meath were just the beginning of a centuries-long war on so-called witches — a war waged not only with fire, but with fear. "Burn the witch!," indeed.

About the Creator

Wade Wainio

Wade Wainio writes stuff for Pophorror.com, Vents Magazine and his podcast called Critical Wade Theory. He is also an artist, musician and college radio DJ for WMTU 91.9 FM Houghton.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.