Einstein's Europe

Chapter 2 : The Café Debates of Zürich

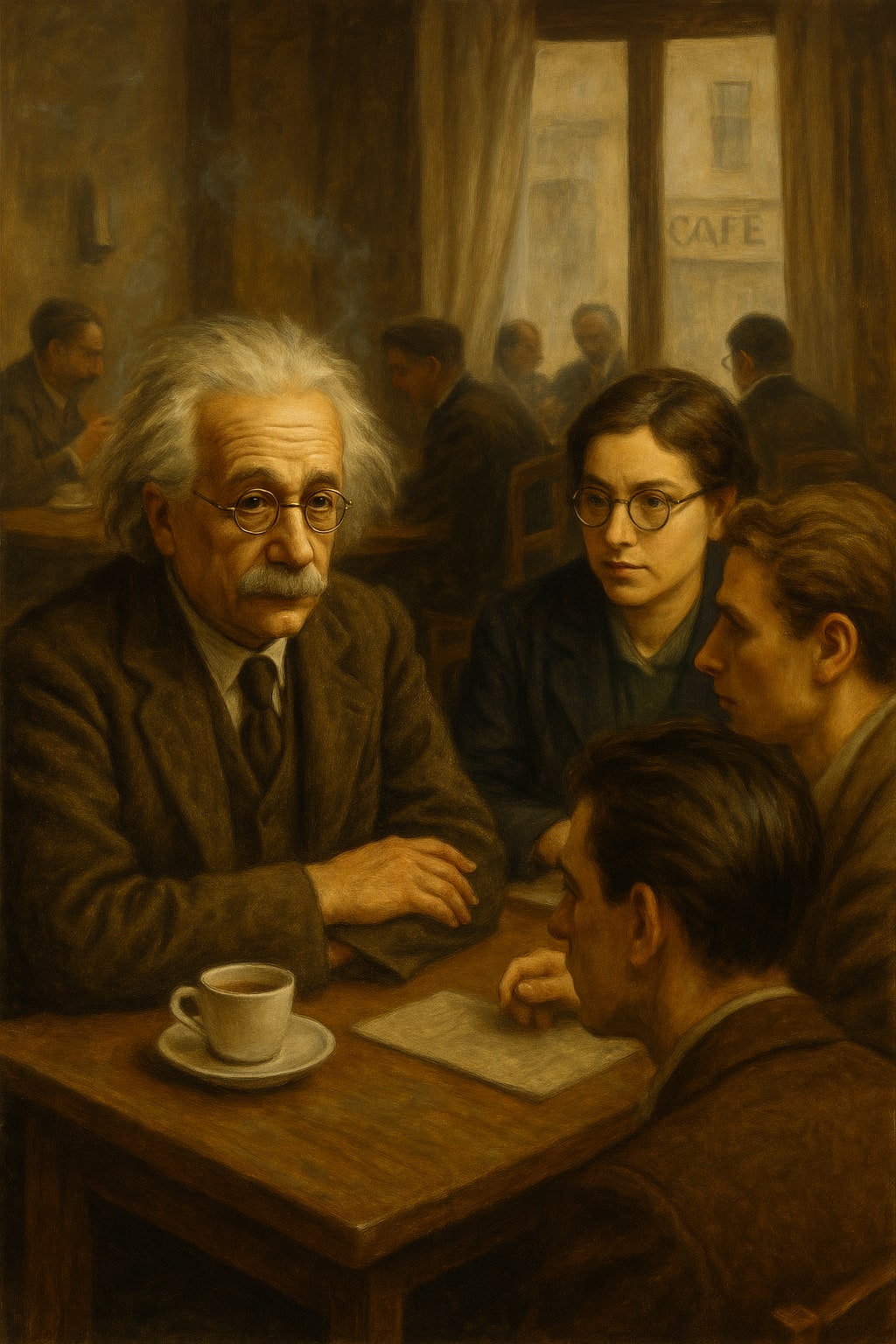

In the spring of 1934, Einstein had settled into a rhythm in Zürich, teaching occasionally at the ETH (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule) and frequenting a modest café tucked along the Limmat River. Its interior was perpetually smoky, the tables often cluttered with books, pipes, and the impassioned hands of those arguing ideas. It was there, in the Café Morgenstern, that a new kind of resistance began to form—not one of arms, but of thought.

Unlike the United States, which was rapidly militarizing its research institutions, Switzerland still clung to neutrality. Einstein, who had turned down Princeton’s invitation to remain in Europe, was convinced that intellect must serve humanity before any nation. He called it the Responsibility of the Mind. This concept became the invisible glue that bonded the circle of young thinkers and dissidents who began to gravitate toward him.

Among the regulars was a Viennese mathematician named Klara Hoch, a fervent anti-fascist who had fled Austria, and the Romanian physicist Andrei Ionescu, whose family had been imprisoned by the Iron Guard. They debated everything from Gödel’s incompleteness theorem to the politics of pacifism. But increasingly, as Germany’s shadow grew longer, their conversations turned to the nature of resistance.

Einstein would sit at the corner table, nursing black coffee and sketching equations on the backs of newspaper margins. He rarely spoke unless prompted, but when he did, the café would fall silent. “It is not enough to be clever,” he once told them. “The world is drowning in cleverness. We need moral courage. That is what they fear.”

What “they” feared was now becoming clearer. The Nazis had not only banned his writings but were persecuting anyone in Germany who was associated with his ideas. Relativity had been branded “Jewish physics,” and a bounty had been publicly placed on his head. But in Zürich, behind the modest façade of the café, a counter-movement was germinating—one that sought not to destroy but to illuminate.

The café itself became a hub. Einstein’s presence lent it a kind of quiet legitimacy, even protection. Students came from Lausanne, professors from Basel, even underground press members from Berlin made their way through the Alps. They called themselves Die Klaren—“The Clear Ones.” Their mission: to preserve and disseminate suppressed knowledge across Europe, using a network of disguised pamphlets, encoded scientific papers, and symbolic mathematics to outwit censors.

It was Klara who first proposed the idea of embedding messages in equations—a tactic inspired by Einstein’s own penchant for hiding philosophical commentary in the structure of his scientific work. A seemingly benign publication on tensor calculus, when decoded, could carry news of resistance efforts or instructions for safe passage.

In one such encoded paper—“On the Perturbations of Temporal Symmetry in Non-Inertial Frames”—Einstein had hidden a plea for the release of a captured Polish physicist. When questioned by a journalist later, he simply smiled. “Mathematics,” he said, “is the only language that dictators cannot understand.”

But not all was noble or safe. In May, the café was raided. A professor from Berlin, masquerading as a refugee, had been an informant. He had turned over a stack of hidden pamphlets and identified Klara as their printer. The arrest was swift. Einstein was not present at the time—he had been meeting with representatives of the League of Nations, hoping to convince them to intervene on behalf of persecuted scientists.

When he returned and learned of Klara’s arrest, he said nothing. That evening, he sat longer than usual at his table. He stared out the window, across the river, into the dark that had become Europe. He did not touch his coffee.

The next morning, he delivered a lecture at the ETH entitled “Relativity and Rebellion.” In it, he drew parallels between scientific paradigms and social change. He spoke not only of light and time but of conscience, of the need to stand in defiance when truth is suppressed. The auditorium, overflowing with students and visitors, gave him a standing ovation.

Outside, a note had been pinned to the café door, likely by someone in Die Klaren:

“Klara ist frei. Die Ideen leben.”

Klara is free. The ideas live.

She had been rescued, it seemed, by a bribe and a sympathetic guard. Einstein never asked who paid, but rumors said it was his royalties from the German edition of his collected papers.

Back at Café Morgenstern, the debates resumed, quieter but more resolute. Einstein knew now that their mission had changed. This was no longer about preserving knowledge. It was about reclaiming the soul of a continent—one equation, one idea, one liberated mind at a time.

About the Creator

Alain SUPPINI

I’m Alain — a French critical care anesthesiologist who writes to keep memory alive. Between past and present, medicine and words, I search for what endures.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.