The Equations of Fate

Chapter 3: The Prague Accord

March 1934.

The chill of late winter lingered in the air as Albert Einstein arrived in Prague, his steps slow but determined. This time, he was not just a physicist or a philosopher of peace—he was an emissary between old and new worlds. The cafés still bore the scent of roasted coffee and aged wood, but the conversations had changed. Scientists, students, refugees—everyone whispered about the shifting tides in Europe.

Einstein had been invited by Edvard Beneš, the new President of Czechoslovakia, to address a secret meeting of European intellectuals, politicians, and artists who were seeking an alternative future—one where fascism could be opposed not only by arms, but by ideas. It was a concept that Einstein had long championed: knowledge as resistance.

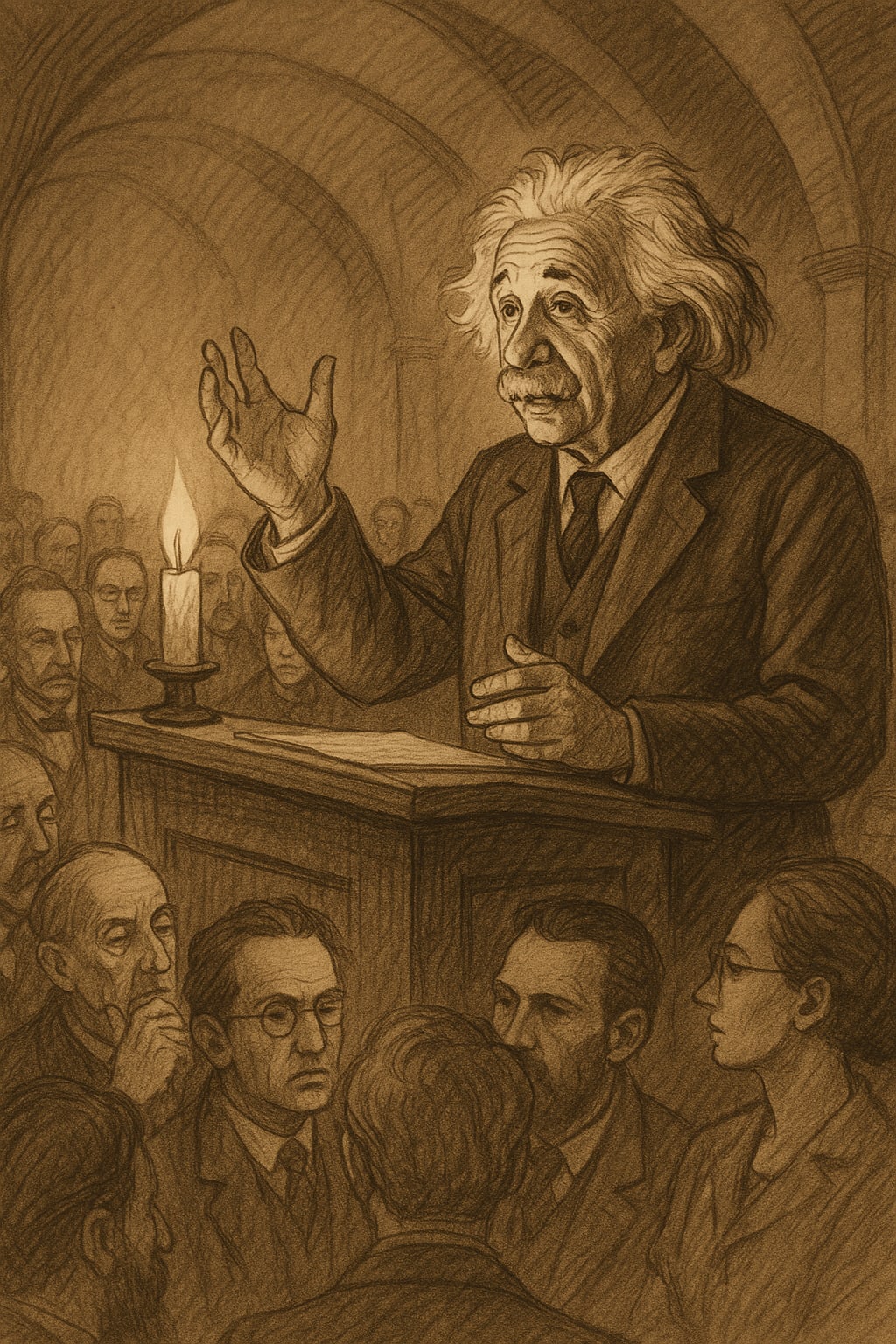

He entered the candlelit conference room of the Charles University under tight security. The audience was eclectic—philosopher Bertrand Russell had come from England, Thomas Mann from Switzerland, and Simone Weil from France. Even the reclusive Romanian sculptor Brâncuși had sent a wooden sculpture titled "Hope" to grace the entrance. Every chair, every gesture, every silence, brimmed with expectation.

Einstein stood before them, not as a politician, but as a beacon. His address began softly, but his voice rose with a tremor of passion.

“When politics stifle humanity, and bombs are designed with the minds of poets, we are no longer in a battle of nations, but of truths. Our responsibility is not to overthrow regimes with force, but to disarm their lies with clarity.”

The speech echoed in the vaulted ceilings. He spoke of a federation of European peoples bound not by borders, but by shared respect for reason, art, and peace. “An equation is not German or Czech,” he said. “A melody is not Jewish or Aryan. Let us remember: tyranny thrives not on the strength of guns, but on the weakness of forgotten beauty.”

The Prague Accord was born that night—not a treaty, not a law, but an understanding. The intellectuals would not flee to silence, nor retreat to isolation. They would publish, teach, compose, and sculpt. Underground newspapers emerged across Europe, their pages filled with reasoned rebuttals to fascist doctrine, scientific treatises smuggled into universities under siege, paintings depicting freedom hung in secret exhibitions.

Einstein returned to Zurich, but the Accord traveled faster than trains. Students in Budapest formed reading circles based on his speeches. A German opera house premiered an allegory of Galileo’s trial as a protest. And when Spanish Civil War volunteers painted Einstein’s face on the walls of Barcelona, it was not as a scientist—but as a symbol of defiance.

Yet all was not hopeful. Back in Germany, Hitler’s regime was tightening its grip. The Nazi Party had begun labeling scientists like Einstein as traitors, banning their books, and interrogating their former students. A professor in Göttingen was arrested merely for owning a copy of Relativity: The Special and the General Theory. In retaliation, the Nazi Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, declared Einstein an “enemy of the Reich,” and his theories “a Jewish infection of the German mind.”

Einstein responded with irony. In a letter published anonymously in international newspapers, he wrote:

“If an idea frightens tyranny, it is not the idea that must be extinguished, but the fear that must be understood.”

The chapter closed with a strange turn: word reached Einstein that a young physicist named Werner Heisenberg had made contact through intermediaries. Once a rising star of German theoretical physics, Heisenberg now struggled with the contradictions of working under a regime that demanded scientific advancement for war. His message was cryptic, but clear: “There are cracks, even in granite.”

Einstein’s reply was sent in coded form through the Prague circle. It contained no equations, no references to physics—only a line from Goethe:

“Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it. Begin it now.”

The seeds were sown. Ideas, now sharper than bullets, began to spread like fire in dry brush.

The next chapter would unfold not in a university hall or parliament—but on a clandestine train bound for Paris, carrying a violin, a journal, and Einstein himself.

About the Creator

Alain SUPPINI

I’m Alain — a French critical care anesthesiologist who writes to keep memory alive. Between past and present, medicine and words, I search for what endures.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.