Einstein in the Shadow of War

Chapter 1: The Letter Never Sent

Zurich, Switzerland — October 1939

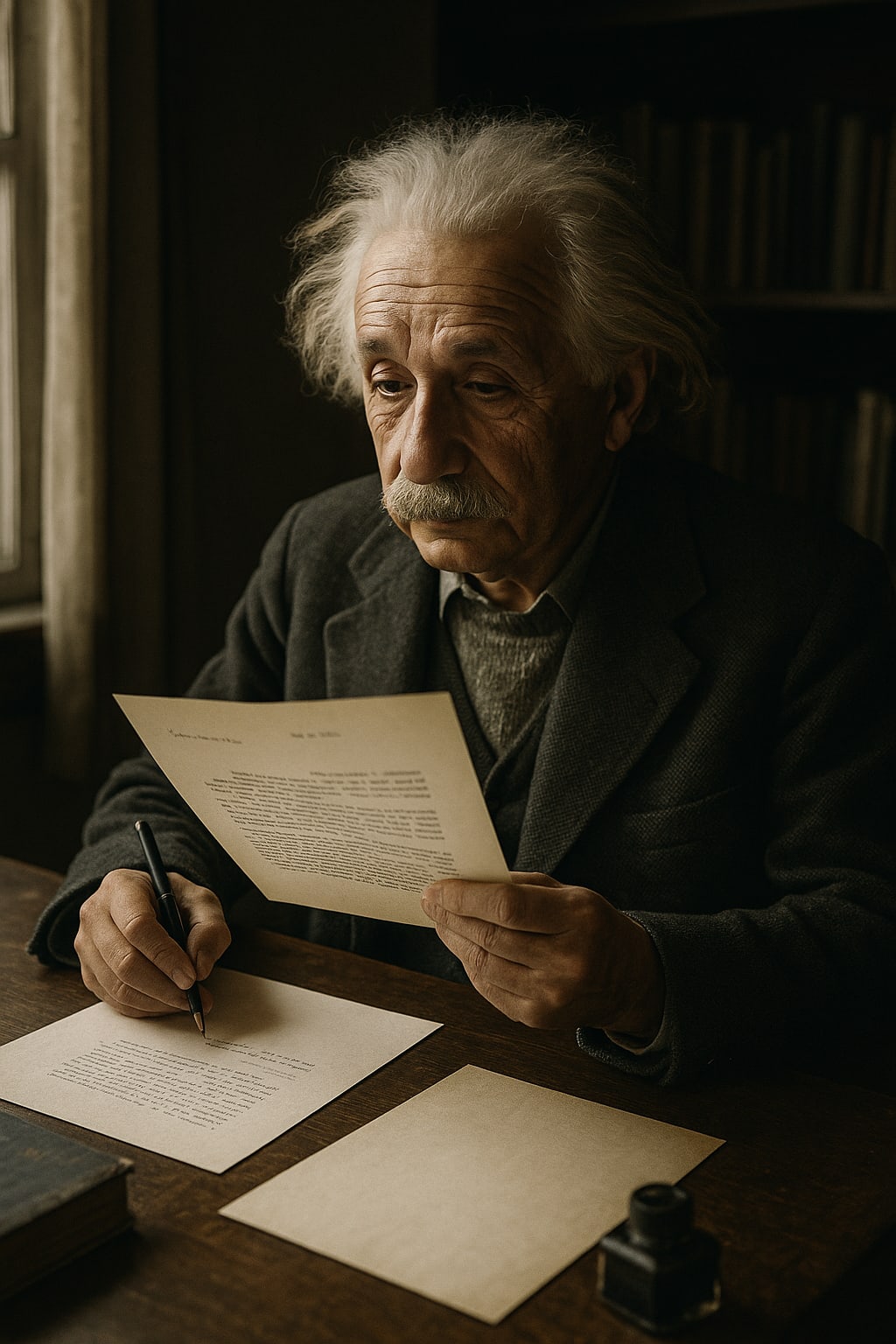

The autumn air in Zurich carried a sharpness that matched the tension humming beneath the surface of Europe. In a modest study filled with the scent of pipe smoke and old paper, Albert Einstein stared at the unfinished letter before him. Its edges curled slightly from the weight of his indecision. Meant for President Roosevelt, the letter warned of the possibility of Nazi Germany developing a nuclear bomb. It was a letter that, in another timeline, would change the world. But here, Einstein had not signed it.

“I will not lend my name to the machinery of war,” he had said aloud to no one, his voice echoing off the walls lined with books on relativity and pacifism.

He had made a choice, months earlier, that diverged from the historical path: he would not go to America.

The decision had shocked many. His colleagues at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton had prepared his office, his residence, and even a position for his loyal assistant Helen Dukas. But Einstein remained in Europe, defiant, principled, and deeply concerned.

“I belong here,” he had said, “amid the chaos and the danger. If I leave, who will speak for the silence that follows the screams?”

In this version of history, Einstein had taken refuge in Switzerland, a nation clinging to its neutrality. He had already escaped the clutches of Hitler's regime once, leaving Berlin in 1933. But unlike other intellectuals who fled west, Einstein chose to stay close to the eye of the storm. He continued to teach and publish, traveling between Geneva, Zurich, and Basel to lecture on physics — and peace.

Now, as Germany invaded Poland and France prepared for war, Einstein’s presence in neutral Europe had turned into a quiet form of resistance. He was not safe. The Gestapo considered him a traitor. Mussolini had denounced him. Even some in Switzerland saw him as a dangerous political figure. But he remained, rooted by the belief that scientific genius could not be separated from moral responsibility.

He folded the letter — unsigned — and placed it back into the drawer. Leo Szilard, the Hungarian physicist who had urged him to write it, would not be pleased.

“They will build the bomb without us, Albert,” Szilard had warned. “We need the Americans to get there first.”

Einstein had only shaken his head. “And what do we become if we race them?”

Outside, church bells tolled the hour. From his window, Einstein could see the golden leaves swirling in the wind, and beyond them, the distant Alps — immutable, eternal. The world was changing, fast. Armies were on the march. Cities would fall. But Einstein believed in another kind of power: the enduring, subversive strength of conscience.

He had found allies in odd places. In Geneva, a group of international scientists — French, Polish, British, even some exiled Germans — had begun to meet clandestinely, forming a kind of “scientific underground.” They hoped to maintain dialogue across borders, to counteract the tide of militarization with collaboration. Einstein was their guiding light, if not their leader.

On this day, one young member of that group — a physicist from Paris named Irène Curie — arrived at his door.

“They have started rounding up the Jewish scientists,” she said breathlessly, coat damp with rain. “Even in Vichy territory.”

Einstein nodded grimly. “We must get them out. The railway to Basel is still open?”

“For now,” she replied.

Einstein’s hands trembled slightly as he poured her a cup of tea. His age was catching up with him. He had been born in the 19th century, a time of monarchs and candlelight. Now the world danced on the edge of atomic fire.

He looked across the table at Irène. “We may not stop the war. But we can save minds. And when the killing ends, we will need minds to rebuild.”

She nodded. “The Americans have the resources, but you still believe Europe can hold on to its soul.”

“I believe Europe must,” he said.

That night, Einstein returned to his equations — a page of tensor notations scattered with ink stains — but he kept glancing at the drawer where the letter sat, unsent. He imagined a world where he had gone to America, had helped the Allies build the bomb, had watched it fall over Hiroshima.

Instead, in this world, he chose uncertainty, danger — and a fragile thread of hope.

As midnight passed, Einstein took out a fresh sheet of paper and began to write, not to Roosevelt, but to Szilard:

Dear Leo,

I cannot in good conscience take part in this arms race. But I will do everything I can to keep Europe’s scientific spirit alive. I hope, in time, you will understand.

Yours,

Albert.

Outside, snow had begun to fall.

About the Creator

Alain SUPPINI

I’m Alain — a French critical care anesthesiologist who writes to keep memory alive. Between past and present, medicine and words, I search for what endures.

Comments (1)

Most valuable content story