When Books Went to War

The Enduring Fight for Literacy and Critical Thought through the Ages

Our book club choice this month was Molly Guptill Manning’s Books That Went to War: The Stories That Helped Us Win World War II. It weaves a compelling story of how literature was used as a tool to bolster morale, increase literacy, and promote democratic values during one of the world’s darkest hours. The distribution of Armed Services Editions (ASEs) during WWII probably began as an effort to entertain soldiers. It ended up as an organic movement democratizing access to literature and encouraging critical thinkers at a time when authoritarian regimes sought to control information.

There are ongoing debates about book bans and the role of reading in a digital age even today. Manning’s book comes as a timely reminder not to repeat history amid concerns about literacy and access to diverse viewpoints.

The Historical Impact of Armed Services Editions

The ASE program dramatically increased access to books among U.S. troops, many of whom had limited exposure to literature before the war. By distributing over 123 million copies of more than 1,300 titles, the program sparked a surge in readership, providing soldiers with both comfort and intellectual engagement. The books were constructed to meet the practical needs of soldiers in the field—small, portable, and lightweight, with stapled bindings and durable paper to endure rough handling. The unique horizontal layout of the ASEs allowed the books to fit easily into uniform pockets while accommodating a wide range of content, from classic literature to contemporary fiction and political science. These features made ASEs a critical tool for soldiers seeking distraction from the stresses of combat, while their accessibility and diversity helped foster a reading culture that many veterans carried with them after the war. The success of the ASEs also contributed significantly to the rise of the paperback format in the United States, which began in the late 1930s with publishers like Pocketbooks. This format showcased the viability of mass-produced, affordable books that appealed to a broader audience.

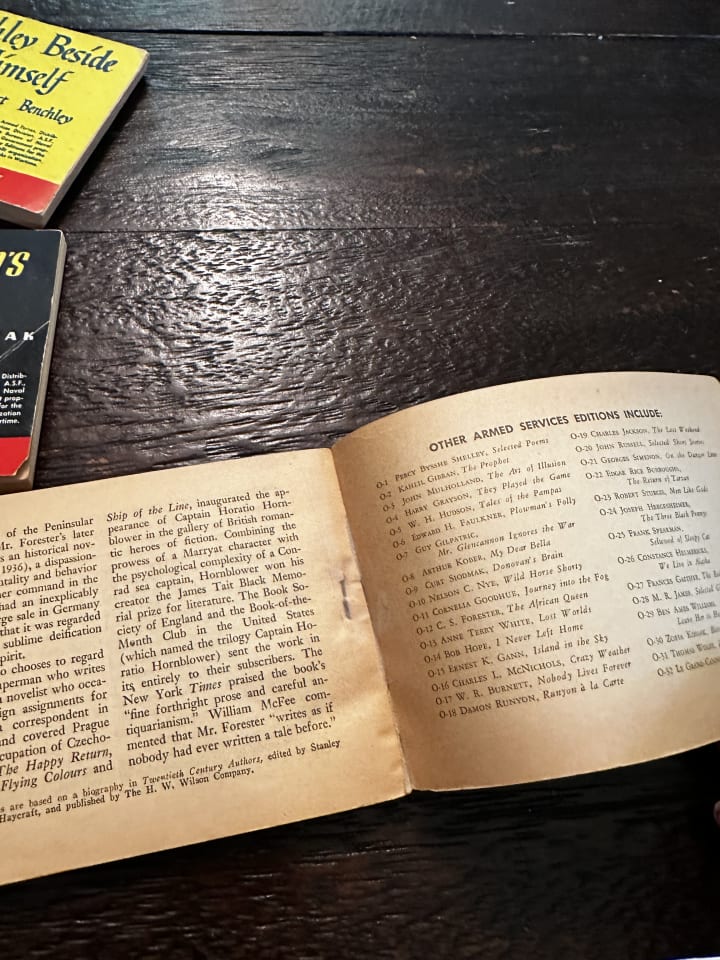

Ginger, one of our creative book club members thoughtfully brought her collection of ASE books to share.

What a wonderful treat it was to use tactile senses in making the connection based on the author description in the book!

As a bookbinder and a humble book artist, I was amazed by the simplicity of the binding with staples, glue, and covers that felt like well-thumbed cardstock. These books innocuously lay on the table, not giving away the power they had over hundreds and thousands of servicemen. The paradox simply boggled my mind; their current muteness had spoken so much to generations before. Yet, we continue to ignore lessons from history.

The program’s impact extended beyond entertainment; it promoted critical thinking by exposing soldiers to complex moral dilemmas and diverse human and cultural experiences. The books did not shy away from addressing challenging social issues, encouraging readers to reflect on broader themes beyond the immediate war effort. Literature provided soldiers with a semblance of normalcy amid chaos, helping them manage their anxiety and fears. As Manning notes, one soldier “lay on the floor of a trench, his body torn by bullets, reading The Count of Monte Cristo.” This act of reading amid danger served as a reminder of the resilience of the human spirit and the importance of maintaining a connection to everyday life, even in the face of overwhelming adversity. This intellectual stimulation helped strengthen critical thinking skills and cultivated a culture of reading that valued deep engagement with literature, which was crucial during a time when totalitarian regimes were using censorship and propaganda to suppress free thought.

Contrasting WWII's Reading Boom with Today's Trends

In today’s world, the context of reading and access to literature has dramatically changed. Unlike the scarcity of books during WWII, the digital age offers an overwhelming abundance of reading materials. E-books, audiobooks, and physical copies are all readily available, which should theoretically increase readership. However, the reality is more complex, as people face numerous competing distractions, such as social media, streaming services, and gaming, which can reduce the time spent reading. The sheer abundance of content has also shifted how people consume information, with shorter, more fragmented reading habits becoming the norm, affecting deep engagement with literature.

While worldwide literacy rates have improved since WWII, the nature of reading and its social significance has evolved. There is a growing emphasis on functional literacy—reading as a practical skill for employment rather than as a tool for personal growth and critical engagement. In contrast, the ASE program was not just about equipping soldiers with basic literacy; it ended broadening their intellectual horizons.

In stark contrast to the values promoted by the ASE program, the German Nazis famously staged book burnings in the 1930s, targeting works that represented ideas contrary to their ideology, including those by Jewish authors, communists, and others deemed "un-German." These public spectacles aimed to rid society of "undesirable" literature and control the narrative, suppressing free thought and promoting conformity. The Nazi regime viewed literature as a potential threat to their authoritarian grip, illustrating the power of ideas to challenge oppression.

The ASE program also faced its own challenges regarding censorship. Certain titles were deemed inappropriate for distribution, reflecting the ongoing tension between the desire for intellectual freedom and the realities of wartime propaganda and moral policing. The reaction to this censorship was largely one of indignation, as many recognized the importance of providing soldiers with diverse perspectives and engaging literature that mirrored the complexities of human experience. Authors, soldiers, and readers alike advocated for a broader range of titles, emphasizing the role of literature in fostering critical thought and resilience.

The Threat of Censorship and the Fear of Repeating History

One of the most significant aspects of Books That Went to War is its underlying message about the dangers of censorship and the power of literature to challenge authoritarianism. The distribution of ASEs was a direct response to the book burnings and censorship practiced by fascist regimes, serving as a counter-effort to promote free access to ideas and protect democratic values. Today, this message remains relevant as book bans and censorship efforts have resurfaced in places like Florida, where certain books are being removed from school libraries due to their content on race, gender, and other sensitive topics.

The fear is that restricting access to literature on controversial subjects may narrow the scope of ideas and viewpoints that students are exposed to, potentially stunting the development of critical thought. Concerns from the past about the dangers of limiting literature and the impact it can have on intellectual freedom have a way of rearing up again. By excluding books that address challenging subjects, society risks revising or sanitizing history, presenting an incomplete picture of the world that prevents future generations from fully understanding historical and ongoing social challenges.

The ASE program embraced a range of perspectives to present a fuller picture of the human experience, while today's book bans may limit this exposure. When topics like racism, historical injustices, or LGBTQ+ experiences are deemed unsuitable for discussion in schools, there is a danger of fostering ignorance about complex social issues. This selective approach to literature can undermine democratic principles by discouraging debate and critical engagement, echoing the methods used by totalitarian regimes to control information and manipulate public opinion.

Literacy, Critical Thought, and the Fight for Intellectual Freedom

The lessons from Books That Went to War remind us of literature’s transformative power and its ability to shape minds and societies. The WWII-era program not only boosted literacy rates but also fostered a culture of reading that valued critical thinking and intellectual resilience. The stakes today are different but no less significant. With the rise of digital media, information overload, and modern censorship, the challenge is to maintain a commitment to deep, thoughtful engagement with literature.

Today’s educational systems must find ways to balance functional literacy with cultivating a genuine appreciation for literature’s broader social and intellectual benefits. Rather than limiting access to diverse perspectives, schools should encourage students to confront challenging ideas and learn to navigate the complex information landscape. This approach will not only promote literacy but also prepare young people to become informed, critical thinkers capable of understanding the world’s nuances. People must have freedom to sift grain from chaff, and a mind trained on multiple perspectives often assists in this habit.

Books That Went to War offers a timeless lesson about the value of literature as a tool for resilience, critical thought, and democratic ideals. Reading also helps defang the power of stupidity. The efforts to distribute ASEs during WWII were a powerful response to censorship and totalitarianism, using books to broaden minds and fortify democratic values. Today, amid ongoing debates about book bans and the role of reading in a digital age, the fear of history repeating itself looms large. As society navigates these challenges, the commitment to intellectual freedom, access to diverse viewpoints, and the promotion of deep engagement with literature remains as crucial as ever. The past serves as a reminder that when books are threatened, the stakes go far beyond the pages—they touch the very foundations of democracy and freedom.

About the Creator

Eyekay

I write because I must. I believe each one of us has the ability to propel humanity forward.

And yes, especially in these moments, Schadenfreude must not rule the web.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.