Vampires of Attention

The Celebrity Exploitation Machine and the Economy of Digital Sacrifice

(a philosophical commentary of ‘’Hollywood Vampires: Johnny Depp, Amber Heard, and the Celebrity Exploitation Machine’‘(2025) Kelly Loudenberg and Makiko Wholey)

Abstract:

This article examines the contemporary transformation of celebrity culture into what Kelly Loudenberg and Makiko Wholey term a ‘celebrity exploitation machine’ in their 2025 study ‘’Hollywood Vampires: Johnny Depp, Amber Heard, and the Celebrity Exploitation Machine’‘. The book does not merely recount the now-infamous legal conflict between Johnny Depp and Amber Heard, but treats the case as a paradigmatic episode in a broader political economy of attention, outrage and affect. The scandal is presented not as an aberration but as a structural feature of a system in which celebrity functions as a raw material to be mined, refined and circulated across media platforms, generating profit precisely through the erosion of truth, privacy and dignity. At the centre of this system stands what may be described as the celebrity-industrial complex: an interlocking network of legacy journalism, social media platforms, influencer cultures, algorithmic ranking systems and monetised fandoms that together produce, amplify and exhaust public figures. In this complex, celebrities are no longer primarily admired or emulated; they are consumed. Their lives are converted into serial narratives, moral melodramas and factionalised wars of interpretation, in which every fragment of testimony, every facial expression and every leaked message becomes a unit of content. The book’s detailed reconstruction of the Depp–Heard trial shows how legal procedure was transformed into a global entertainment format, stripped of juridical context and reassembled as meme, clip, hashtag and partisan slogan. What makes this machine philosophically significant is not only its cruelty but its epistemology. The distinction between fact and fiction collapses not because audiences are deceived, but because deception itself becomes a mode of participation. Loudenberg and Wholey demonstrate how the trial was experienced less as a search for truth than as a competitive game of narrative alignment. Viewers did not ask what had happened, but which version of the story they belonged to. Truth became a matter of allegiance, not evidence, while emotional authenticity was performed through ridicule, rage or ironic detachment. The legal arena was thus repurposed into a theatre of recognition, in which moral standing was measured by virality. The celebrity exploitation machine thrives on this shift from verification to identification. It requires neither accuracy nor closure. On the contrary, the system depends on the endless deferral of resolution. Outrage must be renewed daily, contradictions must proliferate, and reputations must remain perpetually unstable. The figure of the celebrity is thereby transformed into a sacrificial object, repeatedly offered to the collective in order to stabilise fleeting communities of feeling. In this sense, the machine does not destroy meaning; it overproduces it, saturating public space with interpretations that neutralise one another. What remains is not consensus but noise, not judgement but exhaustion. By situating the Depp–Heard case within this broader economy of scandal, ‘’Hollywood Vampires’‘ exposes a cultural formation in which exploitation no longer hides behind admiration, and manipulation no longer needs concealment. The book suggests that the true subject of the trial was never two individuals, but a system that converts human vulnerability into spectacle and monetises moral conflict as entertainment. The celebrity is merely the visible surface of this apparatus; beneath it lies a communicative order in which the very capacity to distinguish between reality and performance is systematically eroded.

Keywords: celebrity-industrial complex, digital sacrifice, attention economy, scandal, fandom, algorithmic media, fact and fiction, moral spectacle

“My father told me something when I was very small to instill confidence in me: ‘Nobody in the world is worth more than you, but nobody’s worth less.’ It is an egalitarian view that I’ve carried around in my life. In America, people think capitalism is freedom. It’s not. It’s only freedom to exploit people.”

Stellan Skarsgård

Introduction: Inside the Celebrity-Industrial Complex

The expression ‘celebrity exploitation machine’ designates a contemporary media formation in which public figures are processed into commodities of attention, scandal, and moral conflict. It names a system rather than a story: a complex interdependence of social media platforms, legacy journalism, public relations industries, advertisers, and networked fandoms that collectively transform celebrity life into a renewable economic resource. Within this celebrity-industrial complex, fact and fiction are no longer stable categories but interchangeable narrative tools, mobilised according to their capacity to circulate, provoke alignment, and sustain visibility. Scandal in this context is not a deviation from normal media practice but one of its most reliable products, because conflict amplifies faster than explanation and outrage sustains attention more effectively than closure.

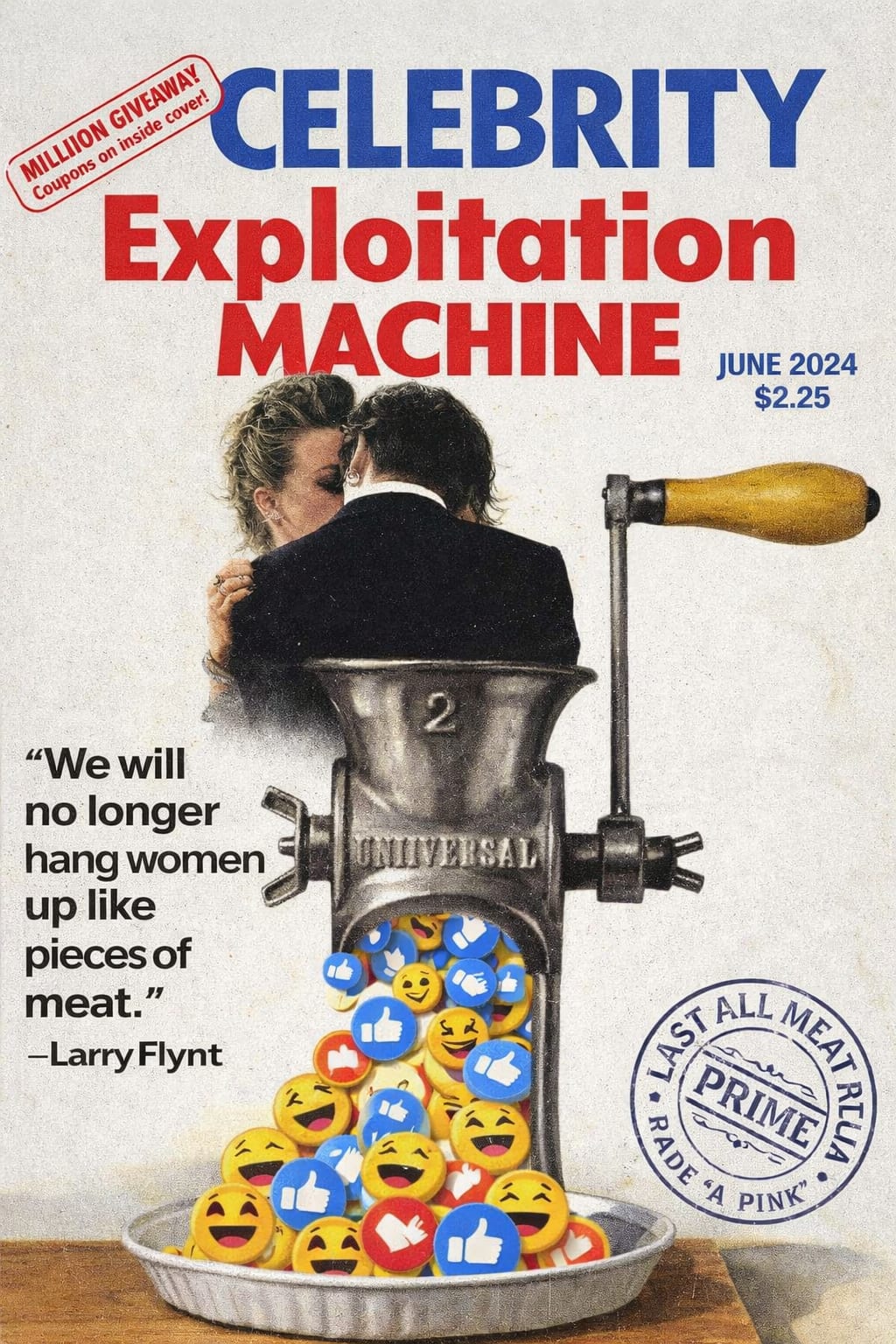

The celebrity-industrial complex can be illustarted by the June 1978 cover of Hustler magazine of a woman literally being ground into meat. While the image originally circulated in a context dominated by second-wave feminism and debates about the subjection of women, today it functions as a broader allegory of celebrity exploitation in which the body being processed by the media machine can no longer be assumed to be exclusively female. The decade in which the cover appeared was marked by expanding feminist politics, symbolised in Britain by the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979 as the first woman prime minister. Against this backdrop, the Hustler image could be read by many feminists as a provocation or even a regression, a pornographic assertion that women were still treated as consumable objects despite social progress. Hustler, founded in 1974 by Larry Flynt as a populist alternative to Playboy and Penthouse, positioned itself as deliberately confrontational, rejecting refined eroticism in favour of blunt shock value. The June 1978 cover depicts oiled legs emerging from a tabletop meat grinder, with minced flesh collecting below. The typography, giveaway slogans, pricing, and the ‘Last all meat issue’ stamp frame the body as a commodity graded and packaged for consumption. At the time, the image was almost universally interpreted as an attack on women’s dignity, especially given the juxtaposition with Flynt’s claim that women would no longer be treated like pieces of meat. Yet the image acquires a different resonance today. In a media environment defined by the celebrity-industrial complex, the grinder no longer processes only women; it processes fame itself. Any celebrity body, regardless of gender, can be fed into the machine of scandal, commentary, fandom, and algorithmic circulation. What once symbolised the sexual objectification of women now reads as a metaphor for the extraction of attention from public figures more generally. Male stars, non-binary influencers, and online personalities are equally subject to dissection, remixing, ridicule, and moral judgement, their images fragmented into clips, memes, and reaction loops. Hall’s theory of representation is useful here, since the image contains multiple layers that shift with cultural context. Detached from its original feminist controversy, the cover can be re-read not only as pornography but as a prophetic diagram of the contemporary attention economy. The body in the grinder is no longer simply a woman reduced to meat; it is the celebrity subject reduced to content. The fetishistic framing of the legs once signalled erotic availability, but now it also signals vulnerability within a system that thrives on exposure and degradation. In this sense, the Hustler cover has outlived its original provocation and become an emblem of a world in which exploitation is no longer gender-specific but structural, embedded in the everyday mechanics of visibility itself.

The idea of the celebrity-industrial complex was first articulated by Maureen Orth in ‘’The Importance of Being Famous’‘ in 2003, where celebrity was described as a symbiotic relationship between individuals who seek visibility and corporate structures that require recognisable figures to anchor brands, headlines, and marketable identities. The celebrity may be elevated for distinctive appeal or pulled into the spotlight through an event that generates sympathy or condemnation, but in both cases the figure becomes a site of intensified media investment. Well-funded distribution systems convert personal life into public narrative, while scrutiny itself becomes a form of capital, capable of producing income, promotion, and momentum for future projects. Attention expands outward to encompass affiliated products, campaigns, and causes, turning reputation into infrastructure. This process is sustained not only by media producers but also by audiences. Fandom operates as a mode of identity formation in which values, gestures, and attitudes associated with a celebrity are adopted as materials for belonging. Participation is no longer limited to watching or reading; it involves interpreting, defending, attacking, remixing, and circulating fragments of a person’s life as if they were ideological tokens. Under such conditions, truth is displaced by alignment. What matters is not what happened, but which version of events one inhabits and promotes.

A revealing reflection on this system appears in a 2018 Vox interview by Eric Johnson with Vanity Fair editor Radhika Jones, where the magazine is described as having played a major role in the creation of the celebrity-industrial complex while also claiming responsibility for holding it to account. Jones acknowledges the tension between access-driven celebrity journalism and investigative scrutiny, noting that in the contemporary media environment access is no longer the ultimate value. The question becomes whether proximity to celebrities brings one closer to truth or merely reproduces the logic of the system itself. Her remarks expose a structural contradiction: the same institutions that helped build the machinery of celebrity are now attempting to interrogate it from within, even as their economic survival depends on its continued operation. This article uses the concept of the celebrity exploitation machine to analyse this contradiction. It treats the celebrity-industrial complex as a communicative order in which personal life is converted into serial narrative, moral conflict into spectacle, and ambiguity into profit. The machine does not merely report on fame; it organises reality around it, draining human experience of context and reissuing it as content calibrated for circulation. In this environment, exploitation is no longer hidden behind glamour but embedded in the everyday routines of media production and consumption.

The next sections retell ‘’Hollywood Vampires: Johnny Depp, Amber Heard, and the Celebrity Exploitation Machine’‘ as a work of celebrity philosophy, drawing on Kelly Loudenberg and Makiko Wholey’s analysis to treat the case not as gossip but as a model of how visibility is manufactured, traded, and weaponised. The emphasis falls on the system: the conversion of private conflict into public currency, the circulation of evidence as entertainment, and the transformation of judgement into a form of collective participation. Individual identities remain secondary to the mechanisms that shape them, because the machine does not require particular people so much as it requires replaceable figures to process. What follows, then, is a reconstruction of their narrative as an anatomy of extraction, showing how fame becomes the medium through which culture thinks, fights, and feeds.

The Vampire Economy: How Celebrity Becomes a Machine of Extraction

Fame appears weightless, like a shimmer above ordinary life, yet it functions as a heavy apparatus that reorganises reality around a small number of visible bodies. The modern city of entertainment, with its banal streets and everyday services, coexists with an invisible infrastructure that converts people into images and images into revenue. That infrastructure is not a metaphorical background to celebrity culture; it is the organising principle of it. The celebrity exploitation machine is the name for this principle: a system that feeds on attention, produces stories faster than understanding, and turns private existence into public property. It operates through a network of intermediaries and institutions that specialise in mediation, interpretation, and monetisation, and it survives because the craving for proximity to the famous is endlessly renewable. Most aspirations collapse before reaching the stage of visibility, but those who do become visible enter a different trap, one in which success becomes a vulnerability and recognition becomes a form of enclosure. The famous person is separated from the ordinary world and placed inside an ecosystem of curated contact, controlled access, flattery, and fear, where nothing is simply lived; everything is potentially content. The machine treats fame as a bargain that always demands payment in the same currency: the self. Public recognition promises security, prestige, and material abundance, but the price is to become legible as a commodity. A public figure is no longer merely a person with a profession; a public figure is a package of meanings that can be bought, sold, revised, and discarded. The body, the voice, the habits, the relationships, the supposed ‘real self’, even the wounds and confessions, become units of exchange in an economy that rewards exposure and punishes ambiguity only when ambiguity fails to circulate. What looks like a life is frequently a portfolio. What looks like personality becomes brand. What looks like intimacy becomes a contract. Even when a person resists this conversion, resistance itself can be processed into market value, because refusal, privacy, and disdain for fame can be stylised as authenticity and sold back to the public as a pose. The machine absorbs every gesture, including anti-commercial gestures, and turns them into proof of uniqueness, which is then leveraged into value. At the centre of this mechanism is not only industry but also ideology. Celebrity does not merely entertain; it becomes a symbolic surface on which political moods and moral debates are projected. A public figure’s personal conflict can be transformed into a proxy for a society’s anxieties, hopes, resentments, and desires for judgement. This is how private pain becomes public theatre. In such moments, the celebrity is recruited as an emblem that is made to represent complex questions that exceed any individual life, and the public is invited to treat a human conflict as a referendum on an era. The machine thrives on this enlargement, because it allows the story to travel beyond its particulars and to acquire the gravity of ‘something larger’. Yet the enlargement is deceptive: it turns social problems into character plots, structural questions into personality tests, and political dilemmas into fandom contests. The larger meaning promised by celebrity drama is often a substitute for analysis, not a path to it.

The conversion of celebrity conflict into mass entertainment becomes most visible when juridical or institutional processes are turned into serial spectacle. Formal procedures that were designed to stabilise truth through rules and evidence are transformed into episodic narratives designed to sustain attention through suspense. The machine does not merely relay the process; it re-edits it, extracting fragments that can be circulated as moral proof. The court becomes a stage, the testimony becomes performance, and the audience becomes a distributed jury that votes through reactions, shares, mockery, and devotion. The event is no longer anchored to a single room; it migrates across screens and feeds, where it is continuously reframed by commentators and reinterpreted by communities. The outcome is a new form of public participation that resembles civic engagement while functioning as entertainment labour. The public is not simply watching; the public is producing the story in real time by choosing what to amplify, what to ridicule, what to sanctify, and what to forget. This is why the question of truth becomes slippery in the celebrity exploitation machine. The machine does not need a stable distinction between fact and fiction; it benefits from the unstable border. Facts circulate when they can be moralised; fictions circulate when they can be weaponised; both circulate when they can be clipped, captioned, memed, and repeated. A statement does not win because it is verified; it wins because it is useful to a side. In such conditions, truth is displaced by alignment. The primary demand placed upon spectators is not to understand but to choose: to decide which narrative one belongs to and to display that belonging. The machine rewards speed, certainty, and emotional legibility, which means it systematically discourages hesitation, complexity, and the slow work of interpretation. Ambivalence becomes suspicious. Nuance becomes disloyal. Doubt becomes weakness. The system does not merely polarise; it trains people to experience polarisation as virtue. The vampire metaphor clarifies what is happening because the machine is extractive by design. It feeds on vitality, attention, and time. It drains the public figure by converting life into consumable spectacle, and it drains the audience by converting moral energy into endless reaction. The machine never reaches satisfaction, because satisfaction would mean closure, and closure would end engagement. Instead, the machine sustains itself through perpetual deferral. Each scandal produces its own afterlife of commentary, reinterpretation, and sequel logic. Every resolution creates new disputes about whether it was real, fair, sufficient, or staged. Every apology invites a counter-apology. Every confession creates a market for analysis. Every piece of ‘evidence’ becomes a pretext for further content. The machine therefore requires a continuous flow of affect, and it secures that flow by keeping the public in a state of interpretive mobilisation, always one update away from final clarity that never arrives.

This exploitation is not only sexual, and it is no longer only gendered in the way older pornographic provocation assumed. The contemporary machine can process any celebrity body, any identity, any persona, because the commodity it seeks is not the body as such, but the body as a carrier of narrative and conflict. Older cultures of spectacle often treated women’s bodies as the primary site of public consumption, but the current economy expands extraction across genders while preserving the logic of objectification. The famous body becomes raw material, whether it is admired, mocked, eroticised, sanctified, or condemned. The machine does not require desire alone; it can feed on hatred, pity, disgust, and moral superiority. A public figure can be consumed through adoration or through punishment, and both forms can coexist in the same audience. The point is not the sentiment; the point is the attention. The machine also reorganises the relationship between fame and merchandise. The famous person is miniaturised into objects, images, and brand surfaces that circulate independently of the person’s actual life. Celebrity becomes detachable, scalable, and portable. An individual can be multiplied into products that outlive the event that made them visible. This multiplication is not incidental; it is the industrial logic of modern celebrity. The person becomes a platform for franchising, and the franchising becomes a form of social presence. The more the person is distributed across objects, the more the person appears ubiquitous, and the more ubiquitous the person appears, the more ‘real’ the person feels as a cultural presence, even as the person as a human being becomes more unreachable. What emerges is a closed loop between idols and idolisation. The system hinges on those who are raised up and those who raise them, those who are displayed and those who demand display. The machine would not function without public appetite, yet public appetite is shaped by the machine’s incentives. People are invited to imagine that participation is empowerment, that reaction is agency, and that the act of consuming celebrity drama is a form of moral involvement. Yet the more people participate on the machine’s terms, the more the machine expands, and the more difficult it becomes to separate genuine ethical concern from the pleasures of spectacle. The celebrity exploitation machine therefore produces a strange moral atmosphere: intense judgement without stable knowledge, passionate allegiance without proportional understanding, and righteous certainty that functions as entertainment. It promises contact with reality while delivering theatre, and it offers a politics of feeling that often replaces a politics of responsibility.

A philosophical reading of this system begins by refusing the comforting idea that exploitation is an exception. Exploitation is the structure. The famous person is not merely harmed by the machine; the famous person is the machine’s most visible fuel. The audience is not merely misled by the machine; the audience is trained into the machine’s rhythms. The intermediaries are not merely opportunists; they are technicians of circulation. The machine is vampiric because it survives by feeding on the vitality of human life and because it requires that life to remain exposed, interpretable, and endlessly reusable. The decisive question is not whether scandal is real or manufactured, but why the system converts any scandal into profit and why participation in that conversion feels, to so many, like belonging.

The Web of Capture: Intimacy, Image and the Mechanics of the Celebrity Exploitation Machine

The celebrity exploitation machine does not operate only through headlines and scandal. Its most decisive work happens in the invisible zones of intimacy, loyalty and psychological alignment, where private relationships are reorganised around visibility and advantage. Fame does not simply surround a person with opportunity; it reconfigures the architecture of trust itself. Old networks of family, friendship and professional continuity dissolve, replaced by a fluid constellation of people whose proximity is measured less by care than by usefulness. The famous subject gradually inhabits a curated social universe in which admiration, access, ambition and dependency are indistinguishable. The result is not simply isolation but enclosure: the shrinking of the world to a single orbit, inside which the individual is continuously mirrored, affirmed and redirected. This enclosure is reinforced by a form of emotional capture. New relationships do not merely attach themselves to the famous person; they wrap around the celebrity identity itself, fusing intimacy with image-management. Conflicts that would otherwise remain personal are converted into scenes that are later mobilised as evidence, leverage or narrative capital. The machine thus turns relational life into raw material. Arguments, reconciliations, excesses, gestures of care or cruelty all become future assets in a story economy that never stops revising the past. The more volatile the relationship, the richer the archive of usable material. What appears as chaos at the level of experience is often, at the level of circulation, an abundance of content. The system thrives on a specific form of psychological technique that might be described as strategic self-fiction. Public figures are taught, formally or informally, to craft personas that feel spontaneous while remaining legible to the media. This practice is less about lying than about staging plausibility. An identity is assembled from arresting details, contradictory traits and rehearsed anecdotes that can be deployed to maintain curiosity. The self becomes a narrative platform, calibrated for quotation, surprise and intrigue. Under these conditions, sincerity ceases to be a stable property of the person and becomes a variable of performance. The machine rewards those who can oscillate between vulnerability and spectacle, between confession and provocation, because such oscillation sustains the attention cycle.

This strategic self-fiction extends beyond interviews into everyday conduct. Social spaces become audition rooms, friendships become networking events, and spontaneity becomes an investment. The celebrity is encouraged to think of encounters not in terms of shared presence but in terms of potential extraction: who might be useful later, who might amplify a story, who might be persuaded to remember something in a particular way. The result is a moral inversion. The virtues that sustain ordinary social life, discretion, loyalty, patience, gradually lose their value, replaced by visibility, momentum and narrative advantage. Even error can be repurposed, because failure, when properly framed, becomes a dramatic asset. The exploitation machine also colonises the formation of the self long before fame fully arrives. Aspirants are schooled in how to make themselves interesting to the press, how to cultivate angles, how to treat their own lives as reservoirs of marketable peculiarity. Craft is secondary; image is primary. The person learns that to exist in the system is to be quotable, clickable and narratable. Education in this environment does not prioritise mastery of a discipline but mastery of circulation. Success becomes a function of how effectively one can insert oneself into existing attention circuits. In this way, the machine produces its own future fuel: individuals who have internalised the logic of exposure before they are even visible. The role of sexuality in this system is illustrative. The body is not merely displayed; it is coded as a signal of ambition, rebellion, intelligence or authenticity. Sexuality is mobilised as a flexible resource that can be aestheticised, politicised or intellectualised depending on the context. The machine does not punish self-exposure; it monetises it. Yet this monetisation does not liberate the subject from objectification. On the contrary, it refines objectification into a style. The subject appears empowered while remaining structurally consumable. What once functioned as transgression is absorbed as branding, and what once signalled vulnerability is reframed as agency, provided it remains profitable. Parallel to this self-production is the industrial manufacture of myth. The celebrity exploitation machine does not merely record life; it writes legends. Childhoods are retroactively shaped into origin stories, habits are reinterpreted as destinies, accidents become symbols. These myths are not imposed from outside; they are co-produced by public figures, their intermediaries and the media that circulate their narratives. The machine prefers stories that imply inevitability, that suggest the person was always meant to become what they have become. In doing so, it erases contingency and labour, replacing them with fate. The public consumes not a biography but a script.

The danger of myth is not that it distorts the past but that it fixes the present. Once a persona hardens into a recognisable type, deviation becomes costly. The individual is trapped by the image that originally generated attention. The more recognisable the persona, the more difficult it becomes to evolve without losing relevance. Image becomes a long shadow that follows the person even when the conditions that produced it have vanished. The celebrity is therefore bound not only to the audience but to a version of themselves that is continually reanimated by others. This is a form of temporal captivity: the present is colonised by archived expectations. As intimacy is instrumentalised and identity mythologised, the boundary between personal crisis and public event dissolves. Breakdown, addiction, conflict and instability are not merely tolerated by the machine; they are actively harvested. The exploitation machine is not moral in the sense of seeking good or evil; it is energetic in the sense of seeking intensity. It requires peaks and crashes, reversals and revelations. Stability is uninteresting. Content arises from disturbance. For this reason, those who attempt to retreat from visibility often find that withdrawal itself becomes a story, framed as mystery, scandal or betrayal. The machine does not allow clean exits, because exits interrupt the flow of extraction. The capture is reinforced by institutional structures that treat the famous person as a financial instrument. Revenue streams are projected into the future, expenses are justified by expected returns, and the person becomes a portfolio that must be managed, optimised and defended. When income falters, the solution is rarely simplification; it is acceleration. More projects, more exposure, more risk. The celebrity is urged to outrun their own exhaustion. The result is a paradoxical situation in which immense wealth coexists with chronic precarity, because the machine demands perpetual motion. The famous subject becomes indispensable to a system that is indifferent to the subject’s endurance.

Finally, the exploitation machine reproduces itself through ritual. Engagements, celebrations, appearances and declarations are staged as communal moments that appear intimate while functioning as broadcast events. Even attempts to control the narrative through privacy, exclusivity or restriction are folded back into the spectacle as proof of importance. The more tightly access is managed, the more valuable access becomes. Scarcity intensifies desire, and desire intensifies extraction. What looks like a personal milestone is often an industrial checkpoint, a moment when the system renews its claim on the individual. In this way, the celebrity exploitation machine operates less like a factory and more like a web. It does not seize; it entangles. It does not simply exploit; it re-educates, teaching people to see themselves as stories, their relationships as leverage, and their crises as assets. It does not destroy individuality in a single blow; it erodes it through attention, affirmation and dependency. The tragedy is not that people are used, but that they learn to use themselves in advance of being used, anticipating the machine’s needs and adjusting their lives accordingly.

Neurontin, Trust and Discretion: Pharmaceutical Governance and the Hidden Logistics

The celebrity exploitation machine does not run only on scandal and spectatorship. Its most decisive work happens in the background, where continuity is protected by a hidden infrastructure of management, secrecy and chemical stabilisation. At the centre stands a fragile economic organism: a single person whose body, reputation, schedule and moods are converted into wages for dozens, sometimes hundreds, of dependants. Under that pressure, the famous subject stops being treated as a human being with limits and becomes an infrastructure that must not fail. Every crisis becomes a logistical problem, every emotional rupture a production risk, and every relapse a threat to payroll. In this system, ‘care’ is easily reframed as ‘continuity’, and the language of wellbeing becomes a vocabulary for keeping the machine running. The point is not simply to help a person recover; it is to stabilise an asset and preserve operability. This is where pharmaceutical governance becomes central. Modern celebrity culture has developed a substitute for ordinary support: a private, mobile, confidential apparatus of medical and quasi-medical control that travels with the star, monitors the star, and responds to volatility in real time. It is presented as compassion, but its structure resembles crisis containment. Instead of withdrawal in a clinic that removes the subject from circulation, the subject is kept in circulation under supervision, with the body managed through prescriptions, sedatives, mood stabilisers and sleep aids that promise control without disappearance. The machine prefers this arrangement because it protects the image, avoids institutional exposure and keeps production on schedule. The ethical problem is not merely overprescription. The deeper issue is that medication becomes a social technology for sustaining a persona. Slurred speech, erratic behaviour, sudden rage, emotional blankness or strange detachment can be recoded as side effects, withdrawal, insomnia, anxiety or the aftermath of ‘strong meds’. Such explanations can be partly true, but they also function as narrative insurance, allowing public disorder to be translated into a therapeutic frame that keeps the wider economy intact. This pharmaceutical layer shifts the internal politics of intimacy. When addiction and instability are managed inside a partnership, intimacy becomes indistinguishable from supervision. One person is encouraged to act as caregiver, monitor, mediator and moral witness at once. That arrangement produces a power imbalance, because the partner who ‘helps’ gains access to the most damaging knowledge: weakness, relapse, desperation, confession, private recordings, medical notes, and the archive of breakdown. Even when intentions are sincere, the structure invites coercion. The caregiver can become the gatekeeper of substances, sleep, movement, communication and reputation. Care becomes leverage, leverage becomes control, and control can be disguised as devotion. At the same time, the machine trains everyone around the celebrity to think in terms of documentation. Arguments are no longer only arguments; they are potential evidence. Messages are no longer only messages; they are future exhibits. Medical notes are not only clinical notes; they are narrative assets. The system rewards those who can produce receipts, because receipts control the story. This is why celebrity conflict hardens so readily into legal conflict: both are extensions of the same attention economy, in which credibility is contested through fragments of private life. The addiction-management regime is also tied to schedules that act like an external authority over the body. When filming, touring or promotional obligations are active, total recovery is postponed in favour of functional performance. Detox becomes something to plan, time and schedule, as if dependency were a calendar item. The logic is simple: the person can be ‘maintained’ now and ‘fixed’ later. Yet later rarely arrives, because later becomes the next project, the next flight, the next obligation. This produces a permanent state of provisionality in which the individual is perpetually ‘almost getting better’, making relapse structurally predictable. The machine then treats relapse not as a moral crisis but as another operational problem to be managed with new prescriptions and tighter supervision. Sobriety itself becomes ambiguous. In ordinary life it often implies a clear boundary; in celebrity life it can be redefined as whatever allows work to continue without public catastrophe. Substitutions are normalised, ‘clean’ becomes flexible, and the measure is not health but employability.

This is where the second system becomes visible: the hidden logistics of trust and discretion. The celebrity exploitation machine survives on a paradox. It demands maximum visibility from its central figure while requiring maximum secrecy about the conditions that make that visibility possible. Publicly, the star must appear coherent, charismatic, and reliably ‘themselves’, even when private life is unstable, chemically managed, and structurally overdetermined by contracts. Privately, everything that might interrupt production must be absorbed, softened, re-labelled, or concealed. Trust means the infrastructure can handle chaos without leaking it. Discretion means the infrastructure can rewrite reality fast enough for the public story to remain intact. Celebrity is not simply an individual but an industrial node. A large production does not employ a single person; it employs a myth, and that myth has a payroll. Delays are expensive, measurable, and punishable, which makes the star both worker and bottleneck, blamed for disruption while remaining indispensable. The contradiction creates a climate of constant emergency: the production must continue and the star must be preserved, even when preservation requires extraordinary measures. The machinery of containment is built from labour designed to be invisible. Luxury housing, private security, drivers, assistants, chefs, and medical personnel are not merely comforts. They are a portable institution whose function is to reproduce a controlled environment wherever the star is sent, so the star can keep working inside a bubble that feels insulated from the world. In effect, celebrity culture exports a private micro-state. Security replaces public order, concierge medicine replaces ordinary healthcare, and household staff replace mundane routines. The promise is comfort, but the deeper purpose is control. The machine cannot tolerate ungoverned time, unobserved conflict or unpredictable exposure. This is why privacy in celebrity life is not simply a right; it becomes a strategic resource, purchased, staged and defended because it protects the flow of value. Yet privacy also creates conditions for the system’s most dangerous dynamics: a closed world where extreme behaviour can unfold without immediate consequence, while everyone around the star is trained to normalise what should be intolerable. When the job is to keep things smooth, crises become ‘incidents’ and damage becomes ‘repairs’. Moral vocabulary is replaced by professional vocabulary. The worse the private disaster, the more important it becomes to appear calm, and the more virtuous it seems to ‘handle it’ without complaint. Discretion becomes a discipline, even when it is functionally denial. Narrative substitution is the machine’s other core technique. When something catastrophic happens, the public cannot be told the truth because the truth threatens the brand, insurers and contracts. An alternative story is manufactured, plausible, banal and easy to repeat. This is not merely public relations but continuity planning. The official story must protect marketability, protect institutions and keep schedules moving. It must also protect the audience’s willingness to keep consuming the persona without discomfort. The public is given a harmless anecdote and the machine continues extracting value from the damaged body and damaged life. Celebrity reality becomes layered: there is the visible narrative of press releases, interviews and curated images, and the hidden narrative circulating among staff, lawyers, doctors and executives. The public narrative may not be false in every detail, but it is designed to be sufficient, sufficient to satisfy curiosity and shut down questions. The private narrative is treated as dangerous knowledge, sealed because leakage triggers lawsuits, cancellation or shutdown.

Loyalty in this system is purchased not only with money but with proximity to power and meaning. People remain close to the star because closeness grants status, access and participation in something that feels larger than ordinary life. The machine exploits that desire by turning staff into disciples. Professional roles bleed into personal roles because the celebrity’s life is a workplace. Boundaries collapse, producing total availability while eroding the distance needed to say ‘no’. In such conditions trust and discretion become instruments of exploitation. Trust means secrecy can be demanded without resistance. Discretion means the inner circle becomes custodian of the lie. Even repair work must avoid ‘raising flags’. Evidence is cleaned, damage is fixed piece by piece, and the logic resembles cover-up while being justified as routine professionalism. The staff member who restores the environment is praised not for asking what happened, but for making the aftermath disappear. The machine teaches a practical metaphysics: what can be made unseen can be made survivable. Accountability is displaced downwards. When powerful people break rules the system reallocates blame. Staff are pressured to provide statements, absorb consequences or remain silent, often through the soft coercion of employment. Those without revenue are expendable; the central asset is protected because the central asset pays. Legal structures reinforce this by turning intimacy into risk management. Contracts, agreements and financial entitlements become the hidden script of relationships. Once wealth and reputation are securitised, personal decisions acquire financial gravity. Emotional bonds are translated into contract problems, suspicion becomes normal, and crises are metabolised rather than resolved. The system cleans the scene, patches the narrative, recalibrates medication, resets schedules and returns the couple or the star to the same space as if nothing happened. The appearance of a ‘reset’ is not evidence of healing; it is evidence of the machine overriding limits. The machine does not ask whether a decision is wise; it asks whether it is workable for continuity. Public embarrassment then completes the loop. When an incident becomes visible, the media reads it as spectacle, audiences consume it, and the internal machine reads it as a crisis requiring new controls. Explanation is demanded and explanation often takes a medical form: medication, withdrawal, insomnia, stress. This may be accurate, but it also serves to keep the star employable by recoding disgrace as treatment. The machine continues extracting value while appearing compassionate. Humiliation becomes content, content becomes renewed attention, and renewed attention becomes salvage value. In this combined view, pharmaceutical governance and logistical discretion are not separate themes but the same mechanism at different levels. Medication keeps the body operable, secrecy keeps the story operable, and both keep the extraction machine running.

Bots and Trolls: The Digital Courtroom of Celebrity Exploitation

Celebrity exploitation did not end when the studio system lost its monopoly on distribution. It simply migrated into a newer infrastructure: platform visibility, algorithmic amplification, and permanent spectatorship. In this environment, reputations no longer rise and fall primarily through performances, interviews, or reviews, but through patterns of online attention that can be manufactured, steered, and weaponised. The celebrity exploitation machine has learned to treat public opinion as a programmable resource. It does not need to persuade everyone. It needs only to generate the impression of overwhelming consensus, then let social pressure do the rest. The core of the contemporary machine is not gossip but coordination. A scandal is no longer merely a story; it is a campaign. The raw material is private life, but the method is industrial: clips, screenshots, selective quotations, and forensic fragments are processed into viral units designed for circulation. Platforms reward this because conflict produces engagement, and engagement produces revenue. The celebrity, whether celebrated or condemned, becomes a reliable generator of attention, and attention becomes the commodity traded by media outlets, fan communities, and opportunistic intermediaries. A person’s intimate life becomes content. A person’s suffering becomes a format. This is the philosophical shift that makes ‘bots and trolls’ so significant. The issue is not simply that cruel messages exist. The deeper issue is that cruelty becomes measurable, scalable, and strategically deployed. Harassment can be coordinated without an official headquarters. It can also be plausibly denied by everyone involved. It thrives in a grey zone where the origin is always uncertain: authentic outrage, fan zealotry, ideological mobilisation, opportunistic clout-chasing, automated accounts, or paid influence. The ambiguity is not a bug but a feature. It allows the machine to maintain deniability while still enjoying the effects. From the perspective of the exploitation machine, online harassment performs three functions.

First, it isolates. When a person becomes a target of a wave, friends, colleagues, witnesses, and casual associates begin to disappear. This is not necessarily because they have changed their beliefs. It is because association becomes expensive. The modern mechanism of intimidation does not require direct threats; it simply raises the cost of solidarity. One accusation, one trending label, one edited clip can make employment risky and social life intolerable. The target loses allies not because allies have been persuaded, but because allies have been priced out.

Second, harassment disciplines speech. The machine does not need to silence everyone. It needs to demonstrate what happens to those who speak. Public punishment becomes a lesson delivered to a mass audience. The spectacle of humiliation tells every observer: avoid this fate. In this sense, the platform is not merely a space of expression; it is a theatre of enforcement. The audience becomes both jury and executioner, not through formal verdicts but through participation in amplification. Each retweet and quote-tweet is a tiny act of power disguised as commentary.

Third, harassment manufactures narrative clarity. Complex events are difficult to monetise because complexity slows consumption. The exploitation machine prefers simple binaries: hero and villain, victim and liar, saint and monster. Online dynamics convert ambiguity into tribal certainty. Once the public is organised into opposing camps, the story becomes a sport. Spectators stop asking what happened and begin asking who is winning. They gather evidence the way fans gather statistics, not to understand reality but to defend identity. The celebrity story becomes a proxy war through which strangers perform their own moral commitments.

This structure explains why modern celebrity litigation becomes a mass entertainment event even when the legal claims involve intimate harm. Courts were designed to resolve disputes through rules of evidence and procedure. Platforms are designed to maximise attention through emotion, speed, and repetition. When a legal battle enters the platform ecosystem, the platform logic tends to dominate. Evidence becomes content. Testimony becomes clips. Documents become memes. The fact that the material is personal is precisely why it circulates: private detail produces voyeuristic thrill, and voyeuristic thrill produces engagement. The exploitation machine depends on this voyeurism, but it also depends on the illusion of moral participation. People do not only watch because they are curious. They watch because they believe they are doing something righteous: defending victims, exposing liars, demanding accountability, protecting men, protecting women, protecting ‘truth’. The machine offers a feeling of civic engagement without the burdens of actual civic responsibility. Clicking becomes a substitute for judgement. Sharing becomes a substitute for proof. Outrage becomes a substitute for deliberation. In this environment, truth is not what can be demonstrated, but what can be made contagious.

Bots and trolls represent the automated edge of this contagion. Even when automation cannot be proven, the suspicion of automation changes how people interpret reality. When a person believes that hostility is manufactured, every hostile message feels like an organised attack, and every supportive message feels fragile. When a person believes that support is manufactured, every supportive message feels like propaganda. Either way, the epistemic ground collapses. The machine benefits from this collapse because uncertainty encourages tribal commitment. If no one can know what is real, the safest position becomes loyalty to a side. This epistemic collapse is intensified by the structure of platforms. Platforms do not show the world; they show a personalised feed optimised for engagement. The result is the sensation that a particular narrative is everywhere. A targeted person sees hostility constantly because the algorithm learns what keeps the person looking. A supportive audience sees supportive content as constant proof that the world agrees. Opponents see the opponent’s worst content as constant proof that the opponent is irredeemable. Everyone experiences their feed as reality. The feed becomes a private courtroom without rules, a tribunal that never adjourns. The exploitation machine has also developed a secondary tactic: evidentiary overproduction. Instead of a single statement, the public is offered oceans of material — texts, recordings, photographs, timelines, and fragments of domestic life. The abundance creates a false sense of transparency. It appears that the audience is seeing ‘everything’, but in fact the audience is seeing a curated selection circulating through hostile interpretation. Excess evidence does not necessarily lead to truth; it often leads to narrative intoxication. People become addicted to ‘new drops’ of content the way they become addicted to episodes of a series. The legal dispute turns into serial entertainment. Each day produces a new clip to react to, a new micro-scandal to argue about, a new moral verdict to perform.

This is where the exploitation machine reveals its most cynical insight: people enjoy moral theatre more than moral understanding. The audience is granted access to private suffering, then invited to translate that suffering into entertainment and identity. A person’s trauma becomes a public puzzle, not for healing but for competition. The promise of ‘justice’ becomes a narrative hook. The desire to ‘believe victims’ or ‘protect the accused’ becomes an aesthetic posture displayed through hashtags. In that environment, the individual at the centre is no longer treated as a human being with a complex life, but as a symbol whose meaning must be controlled. The machine also exploits a more technical vulnerability: missingness. When records vanish, when timelines have gaps, when devices change, when messages cannot be retrieved, uncertainty becomes a new resource for narrative war. Gaps can be read as evidence of fabrication or evidence of tampering, depending on the allegiance of the reader. The absence of proof becomes proof. The inability to verify becomes a reason to speculate. Speculation becomes content. Content becomes revenue. The machine does not require certainty; it requires momentum. In this sense, ‘bots and trolls’ name a broader condition: the conversion of reputation into a battlefield managed by distributed actors, uncertain authorship, and algorithmic reinforcement. The celebrity exploitation machine profits from both outcomes — celebration and destruction — because both generate attention. It does not need stable truth. It needs only an audience convinced that truth is at stake and that participation is meaningful. The victim of the system is not only the person being harassed. The victim is also the public’s capacity to think clearly, because the machine trains people to treat complexity as weakness and cruelty as a form of righteousness. Celebrity exploitation therefore enters its digital phase as a kind of permanent trial. The court of law has dates, procedures, and limits. The platform trial has none. It is continuous, global, and participatory. It runs on fragments, feelings, and factional loyalty. It rewards punishment over patience, certainty over nuance, spectacle over dignity. Bots, trolls, and fan armies are not anomalies in this system; they are its native agents. In the platform age, exploitation is no longer confined to agents, studios, and tabloids. It is crowdsourced, automated, and monetised — an economy in which the commodity is not only fame, but the destruction and reconstruction of the self as entertainment.

From Crocodile Tears to Leaving Los Angeles: Anatomy of a Star-Grinding Machine

In the final two parts of ‘’Hollywood Vampires: Johnny Depp, Amber Heard, and the Celebrity Exploitation Machine’‘ by Kelly Loudenberg and Makiko Wholey, the narrative reaches its philosophical resolution. ‘Crocodile Tears’ and ‘Leaving Los Angeles’ are not simply epilogues to a scandal; they are analytical lenses that reveal how contemporary fame operates as a system of extraction. What began as a personal conflict is reframed as an industrial process in which emotion becomes evidence, judgement becomes entertainment, and retreat itself is absorbed back into the marketplace of visibility.

‘Crocodile Tears’ is less about whether anyone was sincere and more about the collapse of sincerity as a readable category. In a courtroom turned into a global broadcast studio, feeling is no longer private and no longer owned by the person who experiences it. A tear, a tremor, a hesitation, or a sudden stillness is immediately severed from the body that produced it and circulated as proof of whatever story the spectator already believes. The celebrity exploitation machine depends on this severance. It does not require truth; it requires interpretable fragments that can be endlessly replayed and reinterpreted. Emotion becomes a semiotic raw material, stripped of context and refashioned as content. This dynamic produces a culture of amateur lie detection. Spectators are invited to treat themselves as moral technicians, capable of diagnosing authenticity from facial muscle memory and tone of voice. The book’s ending shows that this is not a mistake but a training effect of platform media. Audiences are habituated to reading people the way they read actors: evaluating credibility through performance qualities such as charisma, coherence, and timing. In this environment, the question ‘Is this person telling the truth?’ quietly transforms into ‘Is this person performing in a way I find believable?’. The tragedy is that celebrity labour is itself a training in performance, which means that the very skills required to survive fame are then used as evidence against the famous when they appear in moments of vulnerability. ‘Crocodile Tears’ also exposes how polarisation is not a by-product of scandal but its primary engine. Once a conflict is framed as a binary, spectators are no longer asked to understand but to choose. Teams form, not around shared knowledge, but around shared identity. Evidence ceases to be evaluated on its own terms and instead becomes a badge of loyalty. Each side curates its own archive of proof, circulating fragments that flatter its worldview and ignoring those that complicate it. The crowd becomes a distributed propaganda system, working without coordination yet producing a coherent atmosphere of certainty. The celebrity exploitation machine profits from this because polarisation multiplies engagement. Every post provokes a counter-post, every clip demands a rebuttal, every accusation becomes an opportunity for more content. The cruelty that emerges in this phase is not incidental. It is monetisable. Ridicule, mockery, themed products, and ritualised humiliation become part of the spectacle. The book shows how easily contempt is packaged as playfulness and how degradation is rebranded as humour. The crowd is permitted to enjoy punishment because punishment is framed as justice, and justice is framed as entertainment. The individual at the centre is no longer a person but a screen onto which social frustrations are projected. This is the modern colosseum: a place where spectators do not merely watch suffering but participate in it, purchasing, sharing, and celebrating it as proof of moral alignment.

‘Leaving Los Angeles’ shifts the lens from public destruction to private aftermath, but the philosophical insight remains the same. Withdrawal from the centre does not end exploitation; it only changes its form. Retreat, reinvention, relocation, and attempts at anonymity are immediately reinterpreted as narrative developments. The celebrity cannot simply disappear, because disappearance itself becomes a story. Privacy is translated into ‘hiding’. Silence is translated into ‘strategy’. Creative work is translated into ‘rebranding’. The machine consumes even the refusal to be consumed. This section reveals the paradox of modern fame: it promises unlimited visibility but delivers inescapability. To be famous is not only to be watched; it is to be owned by systems that cannot allow rest. Homes become fortresses, movements become logistics operations, and ordinary acts of living become liabilities. The book’s closing pages make clear that this is not simply a problem for celebrities. It is a problem for culture itself. When the most visible people in society must live as fugitives from their own reputations, the price of attention becomes visible in the body. ‘Leaving Los Angeles’ also confronts the illusion of victory. In the aftermath of a spectacle, one side is declared the winner and the other the loser, but the machine itself remains untouched. It sells triumph and it sells downfall. It profits from vindication and from disgrace. It monetises comeback narratives as readily as it monetises exile. The system is indifferent to outcomes because outcomes do not stop circulation. What matters is that the story continues to generate reaction.

The two final parts therefore function as a single philosophical argument. ‘Crocodile Tears’ shows how the machine trains spectators to consume emotion as evidence and cruelty as participation. ‘Leaving Los Angeles’ shows how even escape is reabsorbed into the economy of visibility. Together they demonstrate that celebrity exploitation is no longer a matter of individual scandal or personal failure. It is structural. It is built into the way platforms reward attention, the way institutions perform virtue, and the way audiences are invited to mistake judgement for understanding. By the end of the book, the reader is left with an unsettling realisation. The celebrity exploitation machine does not merely exploit stars; it exploits the public’s moral imagination. It trains people to treat suffering as spectacle, sincerity as suspicion, and justice as a form of entertainment. In such a culture, there can be no clean endings. There can only be new phases of extraction, in which every tear, every retreat, and every attempt to begin again becomes another unit of value in a system that feeds, endlessly, on human life made visible.

Conclusion: Drinking Blood in the Factory of Fame: Capitalism, Self-Exploitation, and the Rise of Capitalist Realism

This article has argued that the ‘celebrity exploitation machine’ is not a deviation within contemporary media culture but its most coherent expression. What appears as gossip, harassment, fandom, outrage, confession and redemption is in fact a rationalised system for harvesting a single resource: attention. Attention today functions as a form of social energy, renewable yet exhaustible, extracted from human life and circulated as economic value. It is stored as impressions, converted into data, priced as engagement, redistributed through platforms, advertisers, courts, publishers and influencers. In this sense the metaphor of vampirism is not decorative. The system does not observe celebrities; it feeds on them. Their bodies, memories, addictions, relationships, traumas and confessions are transformed into productive surfaces from which symbolic blood is drawn. This blood is not physical. It flows as clicks, views, trending curves, outrage cycles and parasocial loyalty. The industrial logic beneath this economy is unmistakable. Just as nineteenth-century capitalism mechanised physical labour, twenty-first-century capitalism has mechanised visibility. The factory has not vanished; it has migrated into feeds, dashboards, comment sections and courtroom livestreams. Coal and steel have been replaced by affect and recognition. Celebrity culture is therefore not a marginal spectacle but capitalism’s most advanced testing ground, where the extraction of surplus has moved from labour time into lived experience itself.

The first transformation is from attention to extraction. Under the celebrity exploitation machine, visibility is no longer a by-product of achievement; it is the raw material of production. The celebrity becomes a worker whose primary means of production is the self. No longer securely employed by studios, newspapers or broadcasters, the celebrity is reclassified as an independent contractor whose task is to maintain the continuous circulation of a persona. This persona must never sleep. It must post, react, confess, apologise, provoke, disappear, return and reinvent itself at algorithmic speed. Payment is not a salary but relevance. The wage is not income but survival in the feed. Failure is not unemployment but erasure. The industrial relation is concealed beneath the rhetoric of freedom. Platforms present themselves as neutral infrastructures while functioning as employers who deny responsibility. The studio is replaced by the platform, the agent by the feed, the contract by the metric. What appears as autonomy is in fact misclassified labour, a perfect example of bogus self-employment in which the worker is declared ‘free’ while remaining fully subordinated to invisible systems of control.

The second transformation is from extraction to sacrifice. Because the resource being harvested is not time but being, the system requires ritualised offerings of the self. Celebrity culture therefore becomes a sacrificial economy. Public confessions, humiliations, cancellations, comebacks and spectacular collapses are not accidents; they are the liturgy of the attention market. Each scandal refreshes circulation. Each fall replenishes symbolic blood. Crucially, this sacrifice is no longer imposed from outside. It is internalised. The celebrity learns to cut into private life voluntarily, to bleed trauma on demand, to convert breakdown into brand value. This is the new liturgical order of digital capitalism. It does not destroy the soul; it trains the soul to destroy itself in public.

From sacrifice the system advances to self-exploitation. Here the Faustian structure becomes visible. In the classical myth, the soul is sold to Mephistopheles. In the celebrity exploitation machine, Mephistopheles is redundant. The demon is internal. The contract is signed between the person and the persona, between the private self and the public self. The celebrity no longer sells the soul to an external power; the celebrity becomes the power that consumes it. ‘Me and my famous self’ replaces God and Devil. The selling of the soul ceases to be a transgression and becomes a career trajectory. This structure does not belong only to celebrities. Social media extends it to everyone. First one sells friends and followers, converting social relations into metrics. Then one sells oneself, offering grief, anger, ideology, intimacy and outrage as engagement bait. The celebrity is merely the most concentrated form of a general condition in which every subject is invited to become a micro-enterprise of visibility.

At this point the analysis converges with Mark Fisher’s concept of Capitalist Realism. Capitalist Realism is not simply the belief that capitalism is inevitable; it is the atmosphere in which no alternative mode of existence can even be imagined. The celebrity exploitation machine is Capitalist Realism made flesh. It presents self-extraction as freedom, self-destruction as empowerment, and permanent visibility as self-expression. The system does not force participation. It makes participation feel like the only way to exist at all. To be silent is to vanish. To be offline is to be unreal. To refuse the economy of attention is not resistance but social death. Capitalist Realism thus colonises the imagination. Even critique is absorbed as content. Even retreat becomes narrative. Even suffering becomes a resource. What classical Marxism diagnosed as alienation has now reached its terminal phase. The worker is alienated not only from the product of labour but from the labouring self. The individual becomes manager and managed, overseer and exploited, employer and employee within the same psyche. The factory is no longer spatial; it is psychological. The extraction site is the subject. This is why the language of industry fits so perfectly. The celebrity is not simply famous. The celebrity is an industrial form. A production line of images, confessions, scandals and recoveries replaces the assembly line of material goods. The private life of the star becomes a factory floor on which meaning is manufactured, processed and discarded.

The final transformation is therefore from self-exploitation to capitalist industrial form. Celebrity is no longer a cultural ornament but a mode of production. It teaches society how to live under conditions where identity itself is the commodity. It trains audiences to treat suffering as spectacle, humiliation as entertainment, and judgement as participation. It trains subjects to treat themselves as brands, to optimise their own visibility, to experience their lives as potential content. Under Capitalist Realism, the question is no longer whether exploitation exists, but how deeply it has entered the soul. Vampires of Attention names not an industry at the margins of culture, but the core mechanism through which capitalism now reproduces itself: by teaching people to feed on themselves.

Bibliography

Fisher, M. (2009). Capitalist realism: Is there no alternative? Winchester: Zero Books.

Johnson, E. (2018). Radhika Jones on how Vanity Fair shaped celebrity culture. Vox.

Loudenberg, K. and Wholey, M. (2025). Hollywood Vampires: Johnny Depp, Amber Heard, and the celebrity exploitation machine. New York: HarperCollins.

Orth, M. (2003). The importance of being famous. New York: Henry Holt.

Vanity Fair (2018). Interview with Radhika Jones. New York: Condé Nast.

Hustler Magazine (1978). June issue cover. Los Angeles: Hustler Publications..

About the Creator

Peter Ayolov

Peter Ayolov’s key contribution to media theory is the development of the "Propaganda 2.0" or the "manufacture of dissent" model, which he details in his 2024 book, The Economic Policy of Online Media: Manufacture of Dissent.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.