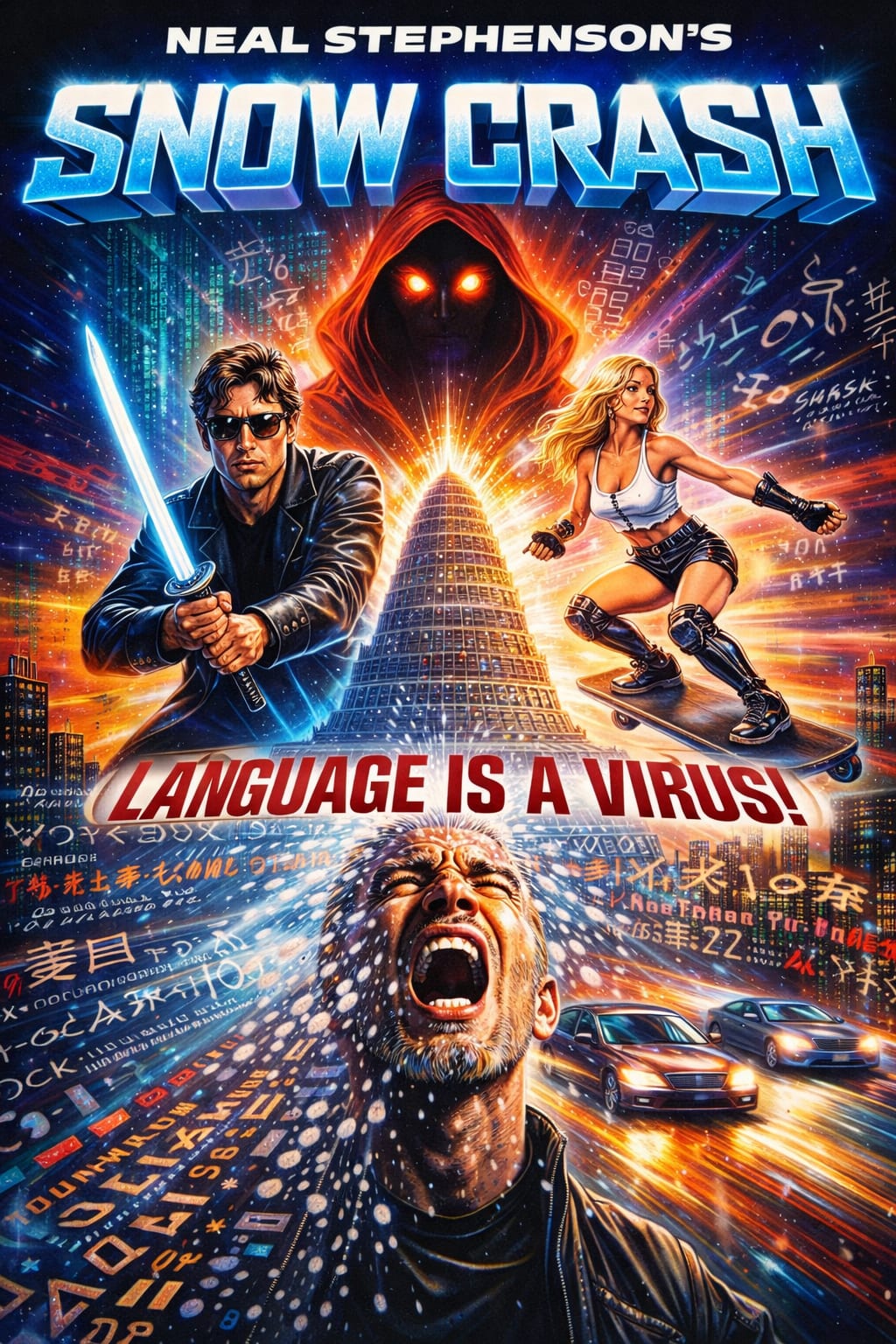

From Babel to Code

Neal Stephenson’s ‘Language Virus’ and the Paradox of Human Speech in the Age of LLMs

Abstract

This article argues that the central intellectual provocation in Neal Stephenson’s *Snow Crash* is neither the Metaverse as a virtual geography nor the novel’s satirical political economy, but the idea of language as a virus: a transmissible code capable of poisoning cognition, reshaping bodily behaviour, and reorganising social order. Stephenson links this viral model to the Tower of Babel as a myth of linguistic fracture and control, then projects it into a modern world where computer languages become the operational substrate of intelligent machines. The contemporary paradox is that large language models, built on formal code and computational syntax, increasingly mediate everyday human expression. Rather than machines corrupting a pure natural language, the argument developed here proposes the reverse: natural human language is itself unstable, illogical, and socially dangerous, and humans increasingly require technological filters to write, speak, and reason coherently. In an emergent environment where utterances are recorded, searchable, and algorithmically judged, language becomes less disposable and more accountable. The article concludes by interpreting this ‘global library’ condition as a new stage of linguistic civilisation, in which the risk of viral speech persists, yet the possibility of responsible language use expands through machine-assisted memory, verification, and form.

Key words

Neal Stephenson; Snow Crash; language virus; Tower of Babel; computer languages; large language models; linguistic mediation; accountability; digital memory; communication paradox

Introduction

Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash is frequently remembered for its prophetic vocabulary of virtual worlds, corporate enclaves, and a culture where reality has been franchised into fragments. Yet the novel’s most unsettling premise is older than its headlong futurism: language functions like a virus. This is not a metaphor offered for colour. It is a theory of power. In Snow Crash, language appears as a programmable agent that can bypass argument, evade deliberation, and rewrite minds at the level of cognitive reflex. The Tower of Babel becomes the mythic template: a story of a once-shared tongue broken into confusion, not merely to diversify speech, but to limit collective agency and redirect human ambition.

That framework now meets a strange historical inversion. Computer languages, designed as precise and rule-governed instruments, underlie the systems that train and operate large language models. These models do not merely process human language; they increasingly sit between people and their own expression, shaping phrasing, correcting errors, reformulating tone, and filtering what can be said in public. The question is no longer whether a metaverse exists, but whether a linguistic regime is forming in which human utterance becomes dependent on machine mediation.

1. Stephenson’s ‘language virus’ as a theory of control

Stephenson’s fictional virus is compelling because it collapses distinctions that modern life tries to keep separate: biological infection, informational contagion, and ideological conditioning. The novelty is not that propaganda spreads, but that language itself is treated as an executable system, able to trigger effects without the consent of the rational mind. The Babel story intensifies this claim. Babel is not only a lesson in human pride; it is an account of how linguistic order can be disrupted to prevent collective coherence. Confusion becomes governance.

The implication is stark: language is not merely a medium for thought but an infrastructure that can be weaponised. If speech is a code, then control over code becomes control over perception. The mind, in this view, is not simply persuaded; it is reprogrammed.

2. From Babel to LLMs: when code begins to govern speech

The contemporary landscape amplifies Stephenson’s central anxiety in an unexpected direction. The machine substrate of language has matured. Computer languages and computational architectures are the conditions of possibility for the systems that now generate, correct, and circulate speech at scale. Large language models exist “in” code, but their products return to human society as prose, instruction, and decision-support. As this mediation intensifies, educated users increasingly draft emails, essays, reports, and even everyday messages through LLM filters, not only to reduce mistakes but to reduce social risk.

The result is a new Babel dynamic. Instead of divine confusion scattering humans into many tongues, algorithmic mediation pulls diverse expression back toward standard forms: safer, smoother, more legible, more compliant. The collective effect is not merely correction but normalisation. People may soon speak and write as if an invisible editor is always present, shaping what can count as meaningful, professional, and acceptable.

3. The paradox of human language: the machine is not the invader

A central reversal follows. The dominant fear says machines will degrade human language. The paradox proposed here says human language has always been the unstable element. Natural speech is ambiguous, emotionally volatile, prone to exaggeration, contradiction, and symbolic violence. It is precisely because language is imperfect that humans developed institutions of grammar, rhetoric, writing, editing, libraries, archives, and law. Machines do not introduce the need for linguistic discipline; they intensify a long civilisational effort to tame the chaos of speech.

From this angle, the ‘virus’ is not artificial intelligence, but human language itself: socially infectious, cognitively contagious, and capable of cascading into collective dysfunction. The technological filter becomes a prosthesis for coherence. The danger is that the filter may standardise too much. The promise is that the filter may make language less reckless.

4. The world as a single searchable library

A final shift concerns memory and consequence. For most of human history, speech disappeared. It created damage, then vanished into air. The digital environment alters this. Increasingly, words are recorded, indexed, replayed, and recontextualised. In such a world, language cannot be used without traces. The speaker’s past becomes retrievable. The sentence becomes durable. The utterance becomes evidence.

This condition resembles a metaverse only in a deeper sense: not a virtual place, but a total archive, a library of human expression where every phrase can be found again. The ethical effect is profound. If language is remembered, it becomes accountable. If accountability becomes normal, the viral potential of speech may be constrained by consequence rather than by moral exhortation.

Conclusion

Stephenson’s enduring contribution is the claim that language can behave like a virus: a contagious code that disrupts cognition and reorganises social reality. The Tower of Babel supplies the mythic grammar of this claim by staging confusion as a political condition. In the present, the viral model returns through a new medium: computational systems that do not merely transmit language but actively shape it. The paradox is not that machines threaten a pure human tongue, but that humans increasingly rely on machines because natural language is unstable, illogical, and often destructive. Under conditions of continuous recording and searchability, speech becomes less disposable and more consequential. The result is not the end of the viral risk, but the possibility of a new linguistic discipline, where machine-assisted memory and correction can push language toward responsibility and, potentially, towards human development rather than decay.

Bibliography

Stephenson, N. (1992). *Snow Crash*. New York: Bantam Books.

About the Creator

Peter Ayolov

Peter Ayolov’s key contribution to media theory is the development of the "Propaganda 2.0" or the "manufacture of dissent" model, which he details in his 2024 book, The Economic Policy of Online Media: Manufacture of Dissent.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.