THE BANK AT THE CORNER HOUSE

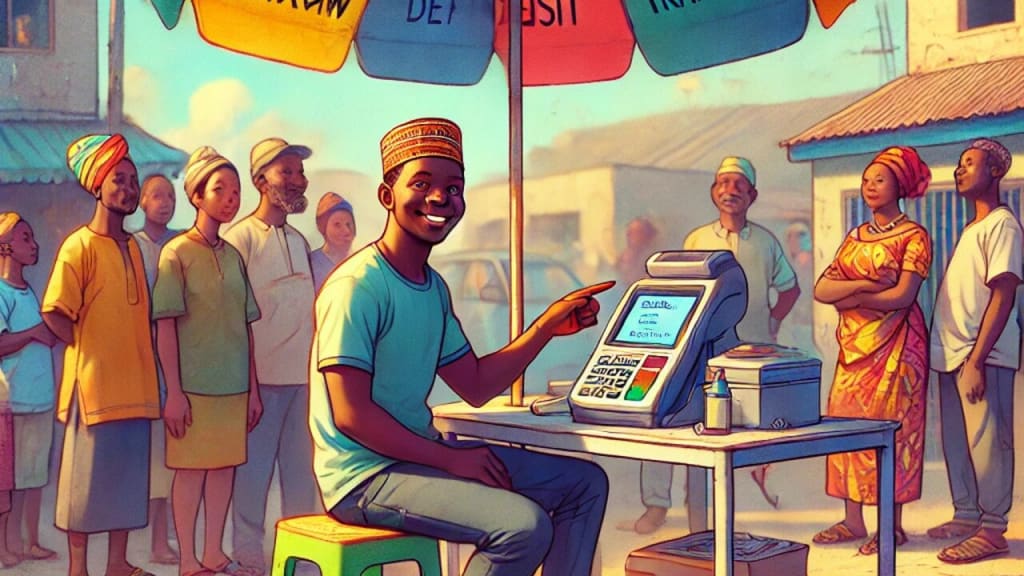

POS Banking System in Nigeria

In 21st century Nigeria, banks had gradually faded into the background of daily life. What was once a symbol of stability and financial security had turned into something many people avoided unless absolutely necessary. Banks in Nigeria had long moved away from being bustling hubs for depositing money or withdrawing cash. Instead, they became a place to resolve issues: correcting debit errors, reversing failed transactions, or dealing with mysterious bank charges that seemed to pop up for services that were rarely, if ever, rendered.

While in many other parts of the world, banks were moving towards seamless, cashless payment systems that offered convenience and security, Nigeria's banking system seemed, ironically, stuck. In the banking halls of major cities like Lagos, Abuja, and Port Harcourt, people still found themselves waiting to make deposits or withdrawals — a reality that clashed sharply with the cashless, virtual banking dreams touted globally. Even ATMs, once a saving grace, had largely lost their utility. Finding one that would dispense more than five thousand naira was increasingly rare; those machines, if they even functioned, were mostly reduced to fancy installations rather than practical tools.

But while banks struggled, something else had filled the gap. At nearly every street corner across Nigeria, you would find the new banking ecosystem — the Point-of-Sale (POS) terminals and their operators. These corner-house POS operators had, in many ways, taken over the roles of traditional banks. Each operator set up under a small canopy, a brightly painted umbrella, or even just a shaded tree with a small signboard that read "Withdrawal, Deposit, Transfer."

The POS businesses offered a unique blend of old-fashioned street commerce and new-age financial services. Here, cash and payments flowed more freely than they did in the banks themselves. For a small fee, one could withdraw money, deposit funds, or transfer amounts in a matter of minutes — no long lines, no malfunctioning ATMs, and certainly no surprise charges. These POS systems had their limitations; they were, after all, designed for quick transactions and convenience, not complex financial services. But what they lacked in sophistication, they made up for in accessibility. In many rural areas, where bank branches were sparse or nonexistent, POS agents became the default bankers.

Ironically, these POS terminals were created in more economically established countries with the simple goal of facilitating payments in stores and small businesses. Yet in Nigeria, they had become a lifeline for millions, evolving from simple payment processors to pillars of daily financial transactions. In other parts of the world, the POS terminal's primary job was to support card payments for purchases, a role it played in the background of daily commerce. But in Nigeria, it had grown to be so much more — an essential service, a reliable alternative, and the beating heart of the community’s financial life.

The legacy of banks in Nigeria had shifted. They were no longer just about transactions and deposits but had morphed into something more nuanced and, frankly, bureaucratic. For the average Nigerian, the bank was now the last resort, a place to solve problems, not manage money.

In the months leading up to the last presidential election in Nigeria, the country experienced an unprecedented period of "cashlessness." This was no government-issued policy or official transition to digital-only payments; rather, it was a consequence of a severe cash scarcity that pushed Nigerians into a struggle just to access their own money.

The crisis began when the Central Bank of Nigeria introduced redesigned naira notes, aiming to control inflation, curb counterfeit currency, and encourage a transition to digital transactions. But the transition did not go as planned. The new currency notes were in short supply, and old notes were being phased out faster than new ones were issued. The sudden currency swap sent shockwaves through the economy, causing confusion, desperation, and, above all, frustration among Nigerians.

In every corner of the country, people were faced with the absurd situation of having money in their bank accounts but being unable to access it. ATM lines stretched down city blocks, with people standing for hours in the hot sun, hoping they’d reach the machine before it ran out of cash. But as the scarcity worsened, many ATMs went dry or limited withdrawals to minimal amounts, often insufficient for people’s needs.

Those who turned to POS agents, hoping for a quicker solution, were in for another shock. With cash so limited, a new, informal "cash-for-cash" system emerged: POS operators, strapped for cash themselves, began charging exorbitant fees for withdrawals. A transaction that would have cost a small fee before now demanded a significant portion of the withdrawn amount. Essentially, people were paying to access their own money, a situation that highlighted the desperation and the unexpected costs of the cashless period.

The scenes were surreal and often heartbreaking. Queues formed not just at banks or ATMs but at small POS kiosks, as people hoped to find even a few thousand naira. For many Nigerians, the frustration ran deep. They were reminded, yet again, of the precarious balance between the formal banking system, which struggled to support them, and the informal economy that offered access but came with steep costs.

During this cashless crisis, digital payments spiked. Those who could, paid with apps, transfers, and mobile wallets. But for the millions of Nigerians without consistent access to digital tools or who relied on cash for daily transactions, the experience was bleak. The ordeal laid bare the gaps in Nigeria’s financial infrastructure and reminded everyone of the power, and vulnerability, of access to cash.

About the Creator

fidel ntui

Step into a realm where every word unfolds a vivid story, and each character leaves a lasting impression. I’m passionate about capturing the raw essence of life through storytelling. To explore the deeper layers of human nature and society.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.