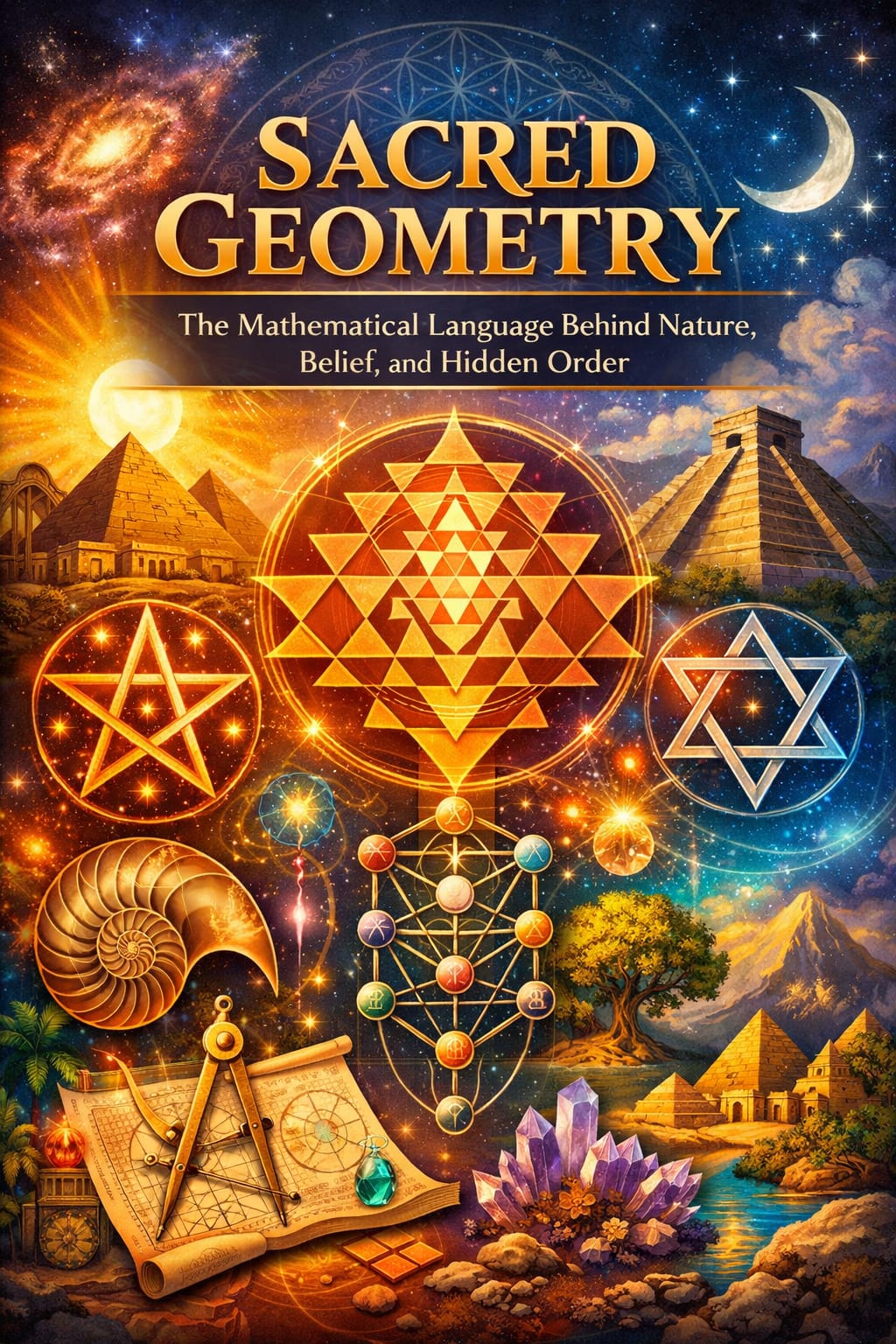

Sacred Geometry

The Mathematical Language Behind Nature, Belief, and Hidden Order

Foundations of Sacred Geometry

Sacred geometry refers to the study of recurring geometric forms, numerical ratios, and proportional relationships that manifest throughout the natural world and across human civilizations. These patterns appear in biological growth, mineral formation, astronomical movement, and the built environment, suggesting that geometry functions as a fundamental organizing principle rather than a human invention. Long before geometry became a formal branch of mathematics, early societies recognized that shape and proportion governed stability, harmony, and continuity in both nature and human life. Observation, measurement, and symbolic interpretation developed side by side, forming systems of knowledge that linked mathematics with cosmology and meaning.

Archaeological and historical evidence shows that ancient cultures employed geometric principles with precision and intention. Stone monuments, ceremonial centers, and urban layouts were designed according to measurable ratios and alignments rather than arbitrary decoration. Egyptian temples followed strict proportional systems based on cubit measurements and cardinal orientation. Megalithic structures in Europe demonstrate awareness of solar and lunar cycles expressed through geometric spacing and alignment. In South Asia, complex diagrams such as yantras were constructed using exact geometric rules and served as visual expressions of cosmic structure. These traditions treated geometry as a language through which order, balance, and continuity could be understood and preserved.

Natural forms further reinforce the role of geometry as an intrinsic feature of reality. The spiral arrangement of seeds in a sunflower follows predictable numerical sequences that maximize spatial efficiency. Shells grow according to logarithmic spirals that maintain proportional consistency as size increases. Snowflakes form hexagonal symmetry due to the molecular structure of water, producing order through physical law rather than chance. Crystals assemble into repeating lattices that reflect internal atomic geometry, resulting in consistent external form. Such patterns arise without conscious design, demonstrating that geometry operates as a structural process embedded within matter itself.

The human body also reflects proportional relationships studied for centuries by physicians, artists, and architects. Skeletal balance, joint articulation, and muscular symmetry depend on measurable ratios that support movement and endurance. Classical systems of proportion used in sculpture and architecture were derived in part from anatomical study, reinforcing the idea that harmony in form supports both function and perception. Geometry in this context does not represent aesthetic preference alone but reflects biological optimization shaped by natural law.

Sacred geometry emerges when these observable mathematical principles acquire symbolic and philosophical significance. Circles come to represent continuity and wholeness because circular motion governs celestial cycles and natural rhythms. Triangles symbolize stability and transformation due to structural integrity and directional force. Ratios such as the Golden Ratio attract philosophical attention because of frequent appearance in growth patterns and visual balance. Meaning arises through the relationship between measurable form and human interpretation, creating systems in which geometry conveys ethical, cosmological, or spiritual insight.

Across cultures and historical periods, sacred geometry has functioned as a bridge between empirical observation and metaphysical understanding. Geometry provided a means of articulating order in a universe perceived as coherent and intelligible. Rather than existing as abstract symbolism detached from reality, sacred geometry developed through careful study of the natural world, architectural practice, and philosophical reflection. This continuity explains its persistence across millennia and its ongoing relevance as a framework for understanding form, structure, and meaning.

Foundations of Sacred Geometry

At its most basic level, sacred geometry is grounded in simple geometric forms whose properties can be measured, replicated, and observed across natural and cultural contexts. Shapes such as the circle, triangle, square, and pentagon are not arbitrary inventions but arise from fundamental mathematical relationships. These forms appear wherever space is organized according to balance, symmetry, and proportion. Because these shapes recur consistently in nature and human design, they acquired layered meanings that extend beyond utility and into philosophy, cosmology, and symbolic thought.

The circle holds a unique position within sacred geometry due to its structural perfection. Defined as a continuous curve equidistant from a central point, the circle embodies unity and completeness through mathematical consistency. Celestial bodies follow circular or elliptical paths, seasonal cycles return in circular progression, and many biological processes depend on rhythmic repetition. As a result, the circle became associated with continuity, eternity, and cosmic totality across cultures. Circular forms dominate ritual spaces, calendars, and symbolic diagrams because they visually express coherence without hierarchy.

The triangle introduces direction and relational balance. As the simplest polygon capable of defining a plane, the triangle provides structural stability in architecture and engineering. This stability contributed to its symbolic association with balance, synthesis, and transformation. Triangular arrangements appear in philosophical systems that emphasize dynamic equilibrium, as well as in religious iconography that reflects threefold principles. The triangle also underlies more complex geometric constructions, serving as a foundational unit for grids, polyhedra, and spatial frameworks.

The square represents order through equal sides and right angles, creating a stable and predictable structure. This form became closely associated with material organization, spatial orientation, and grounded reality. Urban planning, sacred precincts, and architectural foundations frequently rely on square or rectangular layouts because these shapes provide clarity and containment. Symbolically, the square often reflects the structured world, the measurable environment, and the human effort to impose order upon space.

The pentagon and pentagram introduce more complex proportional relationships. The internal angles of the pentagon generate ratios closely related to the Golden Ratio, a mathematical relationship that appears in plant growth patterns and biological symmetry. Because of this connection, pentagonal forms became associated with life, regeneration, and organic balance. The pentagram appears historically as a symbol of harmony between elements and as a representation of the human form inscribed within geometric order.

These primary shapes serve as the foundation for intricate geometric systems such as mandalas, yantras, tessellations, and polyhedra. Mandalas and yantras are constructed through precise geometric rules that govern symmetry, repetition, and proportion. Tessellations rely on the mathematical ability of shapes to fill space without gaps, producing patterns that suggest infinity and continuity. Polyhedra extend planar geometry into three dimensions, offering models for spatial structure and elemental theory.

Sacred geometry approaches these constructions as expressions of mathematical relationship rather than decorative design. Angles, ratios, and spatial relationships determine both form and meaning. Ornamentation remains secondary to proportion, as symbolic significance emerges from the coherence of structure itself. This emphasis on relational mathematics reflects a worldview in which order is not imposed but revealed through careful observation and disciplined construction.

Sacred Geometry in the Natural World

The natural world offers clear and measurable evidence that geometric order is not imposed upon matter but emerges from the laws that govern growth, structure, and motion. Living systems develop according to mathematical constraints that favor efficiency, balance, and continuity. These constraints produce recurring patterns that can be observed, quantified, and modeled, demonstrating that geometry functions as a guiding framework for physical form.

One of the most well documented examples is the Fibonacci sequence, a numerical progression in which each number is the sum of the two preceding values. In botanical growth, this sequence governs phyllotaxis, the arrangement of leaves around a stem. By following Fibonacci spacing, plants maximize exposure to sunlight while minimizing overlap. The same principle appears in seed heads of sunflowers, pinecones, and the spiral growth of shells. These spiral forms follow logarithmic curves that preserve proportional consistency as size increases, allowing organisms to grow without altering structural balance. This pattern does not arise from aesthetic preference but from physical optimization driven by growth mechanics.

Closely related to the Fibonacci sequence is the Golden Ratio, a proportional relationship in which the ratio of a whole to its larger part equals the ratio of the larger part to the smaller. This ratio appears in biological structures where balance and efficiency are required. Skeletal proportions in vertebrates, branching patterns in trees, and certain aspects of human anatomy reflect this relationship. The Golden Ratio also appears in fluid dynamics and atmospheric systems, including spiral storm formations, where rotational forces organize matter into stable yet dynamic structures.

Crystalline structures provide further evidence of geometric order embedded at the molecular level. Crystals form when atoms bond in repeating arrangements governed by electromagnetic forces and spatial constraints. These arrangements produce external shapes that reflect internal symmetry, resulting in predictable geometric forms regardless of scale. Quartz, salt, and snow crystals each demonstrate consistent lattice structures that arise through natural physical processes rather than chance. The external geometry of a crystal directly mirrors its atomic organization.

Snowflakes offer a particularly accessible example of geometric consistency. Each snowflake forms around a hexagonal molecular structure dictated by the bonding angles of water molecules. Variations in temperature and humidity affect surface detail, yet the sixfold symmetry remains constant. This demonstrates how complex visual diversity can emerge from simple geometric rules without disrupting underlying order.

The hexagon also appears in biological engineering through honeycomb construction. Bees construct hexagonal cells because this shape encloses maximum volume using the least amount of material. Mathematical analysis confirms that hexagonal tessellation provides optimal structural efficiency and load distribution. This efficiency supports both strength and conservation of resources, illustrating how geometry governs survival strategies in living systems.

These patterns arise without intention or symbolic awareness, yet they exhibit remarkable consistency across environments and scales. Sacred geometry interprets such regularity as evidence of coherence within the structure of reality itself. Rather than viewing nature as a collection of random events, this perspective recognizes geometry as a stabilizing force that shapes matter through proportion, repetition, and relational balance. The symbolic interpretations associated with sacred geometry emerge only after careful observation of these natural processes, grounding meaning in measurable structure rather than abstraction.

Ancient Civilizations and Geometric Knowledge

Egypt and Mesopotamia

Ancient Egypt presents one of the earliest and most enduring examples of geometry applied as a sacred science. Architectural remains demonstrate that geometry functioned as a governing principle rather than a secondary design choice. Temples, pyramids, and ceremonial complexes were laid out according to precise measurements that aligned with cardinal directions and astronomical events. Surveying techniques relied on standardized units such as the royal cubit, allowing builders to reproduce proportional relationships with remarkable consistency across centuries. These measurements were not merely practical. Orientation toward the rising sun, circumpolar stars, and solstitial points linked sacred structures to cycles of time, death, and renewal.

The pyramids of the Old Kingdom exemplify this integration of geometry, astronomy, and cosmology. The Great Pyramid of Giza is aligned with true north to an accuracy that rivals modern surveying methods. Its base forms an almost perfect square, and its proportions encode relationships between height, perimeter, and slope that reflect deliberate mathematical planning. The pyramid shape itself expresses symbolic meaning through geometry. The square base represents the ordered terrestrial world, while the triangular faces rise toward a single apex, visually uniting earth and sky. This form embodies the concept of ascension and transformation central to Egyptian funerary belief.

Temple architecture followed similarly rigorous principles. Processional pathways, pylons, hypostyle halls, and sanctuaries were arranged along axial lines that reflected cosmological order. Proportional grids governed wall reliefs, statuary, and spatial divisions, ensuring visual harmony and symbolic coherence. Geometry structured ritual movement through space, guiding participants from the outer world toward increasingly restricted and sacred interiors. In this context, geometry functioned as a mediator between the human realm and the divine order believed to sustain creation.

In Mesopotamia, geometric knowledge developed alongside advances in astronomy, agriculture, and administration. The civilizations of Sumer, Akkad, Babylon, and Assyria produced extensive mathematical records preserved on clay tablets. These texts reveal a sophisticated understanding of arithmetic, geometry, and numerical systems based on a sexagesimal structure, which remains influential today through the division of time and angles. Geometry supported land measurement, architectural planning, and the calculation of areas and volumes, but its most significant application lay in celestial observation.

Mesopotamian scholars closely tracked the movements of the sun, moon, and visible planets, recording cyclical patterns that informed calendar systems and ritual timing. Geometric calculations allowed for the prediction of eclipses, seasonal transitions, and planetary positions. Ziggurats, the monumental stepped towers of Mesopotamia, were constructed as elevated platforms that symbolically connected earth and sky. Their tiered geometry reflected cosmic stratification, while orientation and elevation supported astronomical observation and religious function.

Unlike purely decorative architecture, Mesopotamian sacred structures expressed order through scale, proportion, and alignment. Geometry provided a framework through which the heavens could be mapped onto the terrestrial landscape. This mapping reinforced the belief that human society functioned within a larger cosmic system governed by measurable laws.

Both Egyptian and Mesopotamian traditions demonstrate that sacred geometry emerged from disciplined observation rather than abstract speculation. Mathematical precision, astronomical awareness, and symbolic interpretation developed together, forming integrated systems of knowledge. Geometry served as a means of stabilizing human life within an ordered universe, allowing sacred space to mirror the structure of the cosmos itself.

Greece and Philosophical Geometry

In ancient Greece, geometry moved beyond practical measurement and became a central pillar of philosophical inquiry. Greek thinkers treated geometry as a means of accessing universal principles that governed nature, ethics, and knowledge itself. Mathematical study was not separated from philosophy but understood as a pathway toward intellectual and moral refinement. Geometry offered a discipline through which order, proportion, and intelligibility could be examined with rigor and clarity.

The Pythagorean tradition represents one of the earliest systematic attempts to unite number, form, and meaning. Pythagoras and later members of the school held that number constituted the underlying substance of reality. Musical harmony provided a key example, as simple numerical ratios corresponded to consonant musical intervals. This discovery reinforced the belief that harmony in sound, structure, and behavior arose from mathematical proportion. Geometry, in this framework, expressed ethical balance as much as spatial form. A well ordered soul was understood to reflect the same numerical harmony found in nature.

Pythagorean teachings emphasized geometric figures as expressions of cosmic order. The tetractys, a triangular arrangement of ten points, symbolized completeness and the generative structure of the universe. This figure embodied numerical relationships that governed music, space, and time. Such symbols were not treated as abstractions but as representations of natural law, revealing an intimate relationship between mathematics and metaphysics.

Plato further elevated geometry within philosophical discourse. In the Academy, geometry was regarded as essential preparation for the study of philosophy. Plato argued that geometric reasoning trained the mind to apprehend eternal truths rather than transient sensory appearances. For Plato, geometry revealed forms that existed independently of material manifestation. These ideal forms provided the blueprint from which physical reality derived structure and intelligibility.

In the dialogue Timaeus, Plato proposed that the classical elements were composed of specific geometric solids. Fire was associated with the tetrahedron, air with the octahedron, water with the icosahedron, and earth with the cube. The dodecahedron was linked to the structure of the cosmos as a whole. These associations were not arbitrary. Each solid possessed distinct geometric properties that corresponded to perceived qualities such as stability, mobility, or fluidity. Through this model, physical substance was understood as an expression of geometric archetypes rather than inert matter.

Greek architectural theory also reflected philosophical geometry. Proportion, symmetry, and harmonic ratios governed temple design, sculpture, and urban planning. Mathematical relationships guided visual balance and structural stability, reinforcing the belief that beauty emerged from measurable order. The Parthenon exemplifies this integration of geometry and aesthetics through carefully calibrated proportions that create visual coherence and structural integrity.

Geometry in Greek thought functioned as a bridge between the intelligible and the visible. It provided a language through which abstract principles could be expressed in material form. Truth was not perceived as subjective or relative but as discoverable through disciplined reasoning and mathematical insight. Beauty was not a matter of ornament but the visible expression of proportion and order. Within this intellectual tradition, geometry became inseparable from the pursuit of knowledge itself, shaping Western philosophy for centuries to come.

India and East Asia

In South Asian traditions, geometry assumed a profound spiritual and cosmological significance, extending far beyond practical measurement or decoration. In Hindu and Buddhist practice, mandalas and yantras served as structured visual representations of the cosmos, encapsulating principles of balance, symmetry, and hierarchy within carefully calculated forms. These geometric diagrams were designed to guide meditation, ritual engagement, and spiritual insight. Mandalas, often circular and concentrically organized, map the journey from the periphery of mundane reality toward the spiritual center, reflecting the interconnectedness of all levels of existence. Yantras, typically composed of interlocking triangles, squares, and lotus petals, functioned as focal points for concentration, offering a framework in which meditation could unfold with precision and depth.

Among these geometric forms, the Sri Yantra stands as one of the most intricate and symbolically rich. Composed of nine interlocking triangles that radiate outward from a central point, the Sri Yantra embodies the union of masculine and feminine principles, as well as the process of creation and cosmic manifestation. The upward-pointing triangles traditionally represent active, dynamic energy, while downward-pointing triangles symbolize receptive, stabilizing forces. The intersections of these triangles create forty-three smaller triangles, each representing a distinct aspect of existence. Beyond its spiritual symbolism, the Sri Yantra demonstrates remarkable mathematical accuracy, with ratios and alignments that reflect harmonic proportions similar to those found in natural growth patterns and sacred architecture. Constructing or meditating upon the Sri Yantra was considered a method of harmonizing the mind with cosmic order and understanding the structure of reality at both material and spiritual levels.

In East Asia, geometric principles were integrated into philosophical and cosmological systems with similar attention to balance and cyclical movement. Chinese thought emphasized the harmony of opposites, exemplified in concepts such as yin and yang, and the orderly rotation of celestial bodies. Geometry provided a visual and structural language to express these principles. Architectural designs, including imperial palaces, gardens, and ritual complexes, adhered to precise axial alignments and proportional relationships to ensure harmony between human activity and the surrounding natural and cosmic environment. City planning followed analogous principles, with grids and cardinal orientation reflecting an understanding of spatial order aligned with the cycles of the heavens.

Temples, pagodas, and ritual sites in East Asia were constructed with ratios and modular units derived from geometric observation. Symmetry, repetition, and measured intervals guided both aesthetic form and spiritual function. By embedding geometric principles in sacred space, practitioners could experience the universe as a coherent, intelligible system, reinforcing philosophical ideas about interconnectedness, balance, and the cyclical nature of time.

Across South and East Asia, geometry operated simultaneously as a practical tool, a visual language, and a symbolic framework. Whether in the design of a yantra, the layout of a city, or the structure of a temple, mathematical proportion was inseparable from spiritual meaning. These traditions illustrate that geometry is not merely an intellectual exercise but a method for aligning human perception and action with the deeper patterns of the cosmos.

Cultural and Historical Crossroads

Sacred geometry is a universal phenomenon that transcends geographic, temporal, and cultural boundaries, revealing consistent principles of proportion, balance, and cosmology across independent civilizations. When examining the architectural and artistic achievements of ancient societies, remarkable parallels emerge despite limited or no direct contact between them. The pyramids of Egypt, with their precise alignment to cardinal points and carefully calculated proportions, exemplify a sophisticated understanding of scale, symmetry, and celestial correspondence. Across the Atlantic, the stepped pyramids and ceremonial platforms of the Maya and other Mesoamerican cultures reflect strikingly similar attention to proportionality, orientation, and cosmological symbolism. These structures often encode numerical relationships linked to solar and lunar cycles, suggesting that geometric precision was integral to ritual and cosmological observation in both regions.

In South Asia, the construction of Hindu and Buddhist mandalas demonstrates a parallel application of geometric principles, albeit in a symbolic and meditative context rather than monumental architecture. The Sri Yantra, composed of interlocking triangles radiating from a central point, mirrors the same emphasis on proportional harmony and cosmic order observed in pyramidal structures. While the form differs from pyramids or Mesoamerican temples, the underlying concept is consistent: geometry is used to map the cosmos, regulate space, and express metaphysical relationships between the human and the divine.

Comparative study reveals that similar geometric concepts appeared independently across continents because human perception consistently identifies order in nature and the cosmos. Proportions derived from observation of planetary motion, celestial alignments, and natural growth patterns informed architecture, ritual design, and symbolic art. This convergence suggests that geometric insight is not culturally isolated but arises naturally from human cognition and the necessity of organizing complex phenomena. The repeated use of circles, triangles, squares, and harmonic ratios demonstrates a shared understanding that certain forms are inherently expressive of balance, stability, and harmony.

These cross-cultural connections highlight the universality of sacred geometry as both a practical and philosophical tool. While the materials, aesthetic styles, and symbolic interpretations vary, the mathematical and proportional logic is remarkably consistent. By examining structures and symbolic forms from different regions, modern scholars can trace a continuum of human engagement with geometric principles, revealing the persistent human drive to reflect cosmic order in tangible form. The study of these convergent developments underscores that sacred geometry is not merely a regional or historical curiosity but a global language of proportion, perception, and meaning, offering insight into how civilizations across time have sought to understand and harmonize with the universe.

Sacred Geometry in Art and Architecture

Sacred geometry has profoundly influenced art and architecture throughout human history, shaping both the structural integrity and symbolic meaning of creative works. In Gothic Europe, cathedrals exemplified the integration of geometry with religious and philosophical ideals. Architects employed proportional systems to govern every aspect of construction, from the layout of the nave to the precise spacing of columns and the placement of stained-glass windows. Vaulted ceilings, pointed arches, and flying buttresses were designed using mathematical ratios that ensured both stability and aesthetic harmony. Beyond structural necessity, these proportions reflected a symbolic order, guiding worshippers’ perception of sacred space and conveying cosmic balance through visible form.

Islamic architecture developed a distinct expression of sacred geometry through complex geometric tiling and interlacing patterns. These designs often avoided figurative representation in religious contexts, instead emphasizing abstraction to convey the infinite nature of creation and the unity of the cosmos. Patterns such as eight-pointed stars, interlocking polygons, and tessellated surfaces demonstrate precise repetition and rotational symmetry. Geometric ornamentation extended to walls, domes, and floors, creating environments that reflected harmony, order, and spiritual contemplation. The consistent repetition of forms across scale reinforced the perception of a coherent universe in both the material and spiritual senses.

During the Renaissance, artists and architects revisited classical theories of proportion, applying geometric principles to painting, sculpture, and urban planning. Figures such as Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer explored the mathematical relationships that govern natural and human forms, integrating these principles into composition, perspective, and spatial organization. The Golden Ratio, linear perspective, and modular grids guided the placement of elements in a painting, ensuring balance and visual coherence. Architectural works of the period, including churches, civic buildings, and palaces, similarly reflected harmonious proportions derived from geometry, producing structures that were both functional and aesthetically unified.

Sacred geometry in art and architecture served as more than a technical tool. It provided a framework through which beauty, harmony, and meaning could be codified and communicated. The use of proportion, symmetry, and mathematical relationships allowed creators to encode philosophical and spiritual ideas directly into material form. From the soaring heights of Gothic cathedrals to the intricate tiling of Islamic mosques and the carefully measured compositions of Renaissance masterpieces, geometry functioned as a bridge between the tangible and the conceptual, revealing a worldview in which order, balance, and coherence were inherent to both the physical and symbolic dimensions of human experience.

Sacred Geometry and Modern Occultism

In modern occult traditions, sacred geometry operates as both a symbolic language and a structured framework for spiritual exploration. Geometric forms are used to convey metaphysical principles, mediate spiritual experiences, and map the relationships between human consciousness and the cosmos. Unlike decorative geometry, the geometric figures employed in these traditions are designed to encode complex ideas, from the harmonization of elemental forces to the structuring of ritual space and consciousness.

Western esoteric systems, particularly those emerging from Renaissance Hermeticism, Kabbalah, and ceremonial magic, employ geometry as a visual and practical tool. The pentagram, a five-pointed star, has long been central to ceremonial magic. Each point traditionally represents one of the five classical elements: earth, air, fire, water, and spirit. Its geometric precision allows it to function as both a symbolic microcosm of the human body and a tool for focusing intention. Ritual use often involves drawing or visualizing the pentagram to create symbolic protection, establish energetic boundaries, or align practitioners with cosmic order.

The hexagram, formed by two interlocking triangles, represents polarity and integration. In alchemical and esoteric symbolism, it conveys the unity of opposites: masculine and feminine, active and receptive, material and spiritual. The hexagram appears in magical diagrams, ceremonial tools, and meditative visualizations as a means of structuring energy, balancing forces, and guiding transformative processes. Its geometric interrelation of triangles provides a visual model for harmonizing dualities within the practitioner’s consciousness.

Complex diagrams such as the Kabbalistic Tree of Life integrate geometry, numerology, and cosmology to map spiritual ascent, ethical development, and psychological understanding. The Tree’s ten spheres, or sephiroth, are connected by twenty-two paths, creating a geometric network that corresponds to stages of consciousness and archetypal principles. Practitioners use the diagram as a meditative tool, tracing pathways and visualizing connections to explore personal development, ethical alignment, and metaphysical insight. Geometry here functions as a cognitive map, translating abstract spiritual principles into spatial and visual form.

Contemporary occult practice often emphasizes disciplined engagement with these geometric structures. Visualization, ritual circle construction, and symbolic drawing are not left to intuition alone but require rigorous attention to proportion, alignment, and relational balance. The use of geometric frameworks in meditation provides mental focus, structural containment, and coherence, allowing practitioners to engage with abstract metaphysical concepts in a controlled and reproducible manner.

Modern interpretations of sacred geometry vary widely. Some approaches exaggerate mystical claims or detach from historical and mathematical foundations, while historically grounded systems maintain that geometric forms serve as symbolic mathematics rather than instruments of literal supernatural power. Understanding geometry as an organizing principle rather than magical machinery is essential for responsible study. This perspective honors both the historical integrity of esoteric traditions and the practical role geometry plays in structuring ritual, meditation, and symbolic exploration.

Sacred geometry in modern occultism demonstrates that mathematical and symbolic order can serve as a bridge between the material, psychological, and spiritual dimensions of experience. By engaging with these forms attentively, practitioners can explore patterns of consciousness, harmonize internal and external forces, and cultivate a disciplined awareness of structure, proportion, and symbolic meaning within a complex and layered worldview.

Scientific Perspectives and Fractal Geometry

Modern science has revealed that geometric principles extend far beyond classical Euclidean forms, providing insight into natural complexity through the study of fractals and nonlinear systems. Fractal geometry examines structures that repeat similar patterns across multiple scales, a property known as self-similarity. These patterns appear throughout nature: the branching of trees and blood vessels, the jagged contours of coastlines, the formation of mountain ranges, and the structure of clouds all demonstrate fractal organization. Despite their complexity, these forms often arise from remarkably simple mathematical rules, revealing that intricate patterns can emerge without conscious design or intervention.

Benoît Mandelbrot, the mathematician credited with developing modern fractal theory, demonstrated that natural systems frequently generate irregular shapes that resist traditional geometric classification. By applying iterative processes, fractal mathematics models the irregular yet patterned forms observed in nature, bridging the gap between chaotic appearance and underlying order. For example, the spiral phyllotaxis of plants or the recursive branching of river systems exhibits measurable ratios and repetition that can be described mathematically using fractal principles. These observations confirm that natural complexity is not random but follows inherent organizational rules that can be quantified and predicted.

Sacred geometry and modern scientific perspectives converge in their recognition that form and proportion structure reality, although they approach the topic through different lenses. Sacred geometry interprets geometric relationships symbolically and philosophically, emphasizing their aesthetic, spiritual, and ethical significance. Circles, triangles, spirals, and other figures are seen as manifestations of universal harmony and cosmic principles, connecting human perception with metaphysical insight. Science, by contrast, examines these patterns empirically, seeking to describe and model the mechanisms by which complexity arises, from molecular structures to planetary systems.

The intersection of these approaches highlights the universality of geometric order. Both traditions, ancient and modern, demonstrate that observable form is not incidental. Whether through symbolic meditation, ritual construction, architectural design, or scientific modeling, geometry functions as a tool for understanding the coherence underlying apparent chaos. By recognizing the repeated, self-similar structures in both living and nonliving systems, researchers and practitioners can discern the principles governing growth, stability, and interconnection.

Fractal geometry thus provides a scientific lens through which sacred geometric insights can be appreciated in a measurable and replicable way. It reinforces the ancient observation that proportion, symmetry, and repetition are not merely aesthetic choices but are inherent to the structure of natural reality. By bridging empirical observation with philosophical interpretation, the study of fractals and nonlinear systems demonstrates that geometric patterns operate at every level of existence, from microscopic cellular structures to planetary formations, confirming that geometry remains a foundational principle of both nature and human understanding.

Recommended Reading: #commissionearned

Sacred Geometry: Philosophy and Practice by Robert Lawlor

This book provides a rich, historically grounded exploration of geometric principles as they appear in nature, architecture, art, and human culture. Lawlor traces the use of geometric ratios and forms from ancient civilizations through the mathematical and philosophical traditions that shaped Western thought. Readers encounter detailed explanations of the Golden Ratio, logarithmic spirals, and the squaring of the circle as both mathematical constructs and symbolic motifs. The text includes practical geometric constructions that readers can work through to deepen their intuitive understanding of proportion and form. Lawlor’s work situates sacred geometry within philosophical frameworks developed by thinkers in Egypt, Greece, India, and Renaissance Europe, illustrating that geometry has long served as a bridge between empirical observation and metaphysical insight. Rather than presenting geometry as mere ornamentation, the book treats it as an underlying language of coherence that operates across scales of physical and conceptual reality. Its disciplined approach makes it especially valuable for readers interested in the structural relationships that connect cosmos, culture, and consciousness.

Michael Schneider’s book demystifies the recurring geometric patterns and numerical sequences that appear throughout nature and human history. The author uses accessible language to explain how shapes such as triangles, spirals, and polyhedra manifest in biological growth, architectural design, and cultural symbolism. Schneider draws connections between the Fibonacci sequence, the Golden Ratio, and the proportional systems that inform artistic and scientific traditions across cultures. By presenting geometric archetypes as bridges between mathematics and lived experience, the book encourages readers to see pattern as both a descriptive tool and a source of wonder. It situates geometry within a broader web of human knowledge, showing how geometric ratios informed ancient monuments and influenced artistic endeavors during the Renaissance. The inclusion of clear diagrams strengthens comprehension and helps readers internalize abstract concepts through visual reasoning. For those new to sacred geometry, this book offers an engaging synthesis of natural pattern, cultural history, and mathematical insight.

Occult Geometry and Hermetic Science of Motion and Number by A. S. Raleigh

Raleigh’s work bridges traditional occult philosophy with geometric and numerical interpretation, offering a compelling perspective for readers interested in the symbolic dimensions of form. The text combines two classic works on geometry, motion, and number theory from a Hermetic viewpoint, emphasizing how shapes and ratios reveal deeper truths about nature and consciousness. Concepts such as the triangle, cross, sphere, and pentagram are presented not only as geometric figures but also as symbolic keys to understanding the structure of reality. Through lessons on squaring the circle, hexagram formation, and the relationship between motion and number, the book encourages disciplined engagement with symbolic mathematics rather than speculative interpretation. This volume aligns closely with the exploration of sacred geometry, as it treats geometry as a language of structure and meaning, linking physical form with metaphysical insight. Readers will find that the author situates geometry within ancient wisdom traditions, including Hermeticism and Pythagoreanism, illuminating how number and form were historically understood as inseparable. This book offers a practical complement to more academic treatments by framing geometric inquiry as a method for inner exploration and symbolic understanding.

Monas Hieroglyphica by John Dee

John Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica represents one of the most enigmatic and historically significant attempts to unify geometry, astrology, and metaphysics in a single symbolic system. Written in the sixteenth century by the Elizabethan scholar and court astrologer, the text elaborates on a composite symbol that Dee believed embodied the unity of all creation. The emblem combines astrological glyphs, geometric form, and numerical relationships to express a holistic vision of cosmic order and spiritual evolution. Readers encounter a rigorous exposition of symbolic mathematics that reflects the Renaissance pursuit of universal knowledge grounded in both empirical observation and occult philosophy. Dee’s work is deeply connected to sacred geometry, as it treats shape and proportion as expressive of cosmological principles rather than as arbitrary decoration. The text challenges readers to interpret geometric symbolism within the broader context of celestial influence, alchemical transition, and philosophical reflection. This work remains a touchstone for studying the historical intersection of geometry with esoteric thought.

The Book of Thoth by Aleister Crowley

Aleister Crowley’s The Book of Thoth examines the symbolic architecture of the tarot deck through intricate geometric and mythological analysis. While not strictly a geometry textbook, the work interprets the tarot’s structure through ratios, spatial metaphors, and symbolic form that closely relate to sacred geometry and esoteric cosmology. Crowley integrates principles of ceremonial magic, astrology, and Hermetic Qabalah, offering a layered account of how geometric symbolism encodes metaphysical principles. The book is structured to guide readers through both theory and application, allowing geometric form to mediate the interpretation of consciousness and archetypal patterns. Many tarot cards themselves are based on symbolic relationships resembling geometric constructs, such as sequences and networks that mirror proportional systems. This text complements studies of sacred geometry by illustrating how symbolic form can function as a bridge between internal experience and external structure. It remains a significant resource for understanding the interplay between geometry and occult philosophy.

Sacred Geometry: An A-Z Reference Guide by Marilyn Walker PhD

Marilyn Walker’s reference guide provides a comprehensive alphabetical exploration of geometric figures, concepts, and historical figures relevant to sacred geometry. The guide allows readers to investigate specific terms and traditions with precision, making it ideal for targeted research or extended study. Entries cover geometric shapes, notable mathematicians, and the cultural contexts in which geometric interpretation evolved. Each entry balances symbolic interpretation with historical grounding, showing both the mathematical relationships and their cultural or spiritual significance. Illustrations clarify complex visual forms and support deeper comprehension. This reference assists readers in navigating the interdisciplinary nature of sacred geometry, connecting mathematics with philosophy, art, and religious practice. It functions as a practical companion for those seeking structured and disciplined study of geometric principles.

The Kybalion by Three Initiates

The Kybalion encapsulates core principles of Hermetic philosophy that have influenced occult traditions throughout the twentieth century and beyond. Although it is not exclusively about geometry, it articulates foundational ideas about correspondence, vibration, polarity, and rhythm that resonate with geometric interpretations of structure and symmetry. The principle of “as above, so below” parallels the geometric notion that proportional relationships repeat across levels of existence. Hermetic philosophy presented in this book positions geometry as a metaphorical and practical language for understanding how patterns manifest in both the microcosm and macrocosm. Readers learn to see geometric form as a means of structuring metaphysical concepts, ritual, and meditation. The text enriches the study of sacred geometry by situating proportional relationships within a broader philosophical and cosmological framework. It provides historical depth to modern occult systems and underscores the symbolic significance of form in understanding both the universe and consciousness.

Continuing Study with Discernment

Sacred geometry is a field that rewards patience, careful observation, and disciplined engagement with both text and practice. Its study benefits from consulting multiple sources, comparing interpretations, and examining historical and mathematical evidence rather than relying on surface-level explanations. Public libraries provide an invaluable resource in this regard, offering free access to academic texts, historical manuscripts, scholarly journals, and curated databases. Librarians serve as knowledgeable guides, helping readers navigate complex material, identify authoritative publications, and distinguish credible scholarship from speculative or sensationalized accounts. Engaging with physical texts also allows for the study of detailed diagrams, proportional constructions, and annotations that are often lost or misrepresented in digital formats.

While free online resources can serve as useful introductions or starting points, they require careful scrutiny. Many websites blend symbolic interpretation with conjecture, omit essential historical context, or present claims without verifiable sources. Cross-referencing online content with well-documented publications, peer-reviewed research, or recognized academic editions protects against misinformation and encourages critical thinking. Observing this discernment ensures that study remains rigorous and meaningful rather than anecdotal or superficial.

Independent research allows readers to explore sacred geometry in a way that is both intellectually and spiritually enriching. Delving into original texts, architectural studies, natural patterns, and philosophical treatises encourages a deeper appreciation for the principles that govern proportion, harmony, and structure across the cosmos. Careful study also reveals the interconnections between cultures, disciplines, and historical periods, highlighting the universality of geometric insight.

Approaching sacred geometry with curiosity, rigor, and an awareness of source credibility preserves the integrity of a tradition that has shaped human thought for millennia. It encourages a methodical and reflective engagement with forms, ratios, and patterns, while fostering an understanding of their symbolic, scientific, and philosophical significance. By combining disciplined reading, observation, and critical evaluation, students of sacred geometry can cultivate knowledge that is both reliable and transformative, honoring the depth of a field that continues to inspire inquiry and wonder across generations.

About the Creator

Marcus Hedare

Hello, I am Marcus Hedare, host of The Metaphysical Emporium, a YouTube channel that talks about metaphysical, occult and esoteric topics.

https://linktr.ee/metaphysicalemporium

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.