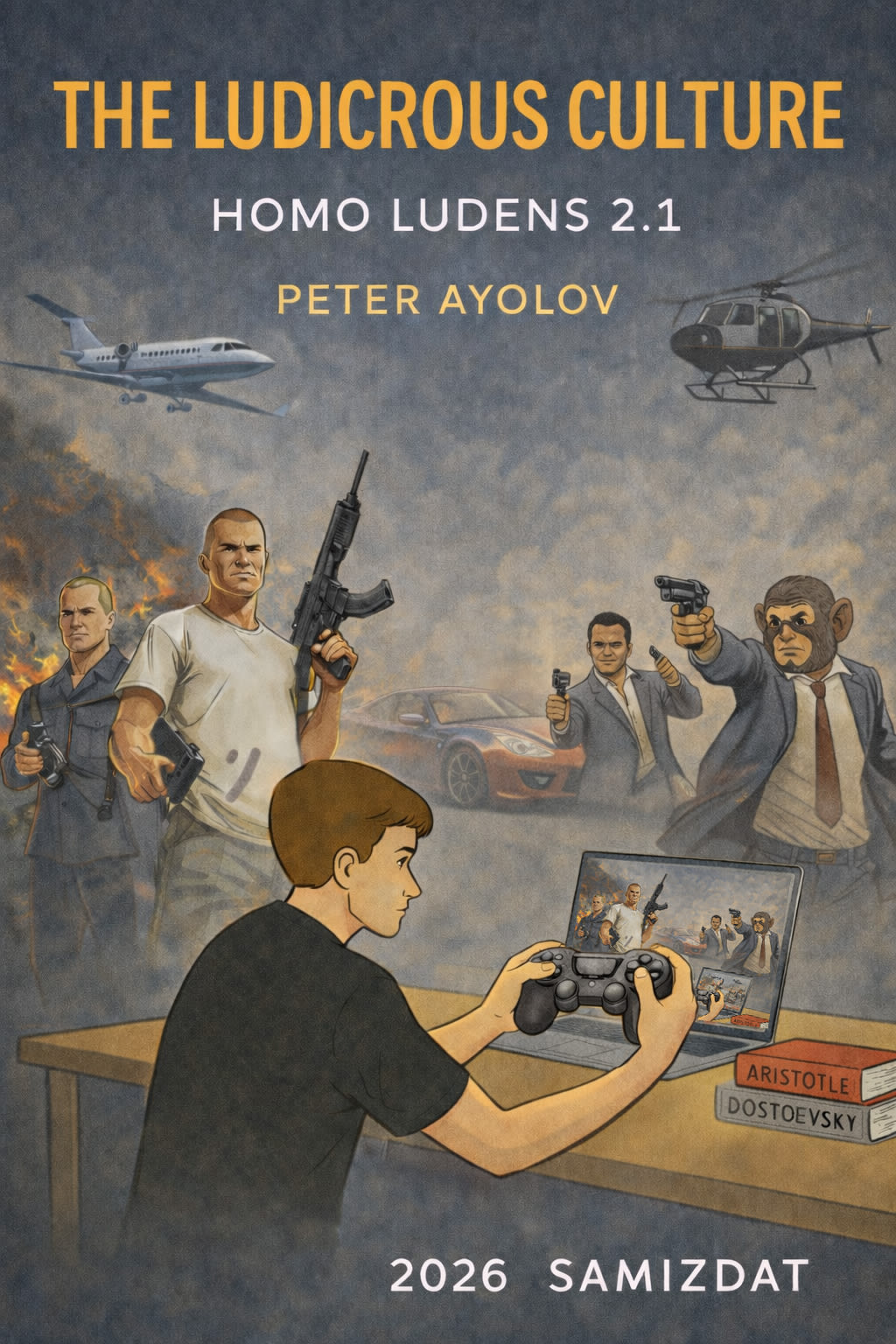

Review of The Ludicrous Culture: Homo Ludens 2.1

Peter Ayolov (2026)

Review of The Ludicrous Culture: Homo Ludens 2.1

Peter Ayolov (2026)

The Ludicrous Culture: Homo Ludens 2.1 is an ambitious and unsettling book. It does not merely revisit the familiar thesis that play is central to culture; it argues that play has become the infrastructure of contemporary life. In doing so, it reframes play from a marginal or liberating phenomenon into a dominant logic of governance, participation, and meaning-making. The book’s central claim—that modern societies have entered a condition of panludism, in which play structures not only leisure but politics, labour, identity, technology, and power—marks a significant conceptual shift in how play is understood within cultural theory.

Rather than celebrating play as creativity, freedom, or resistance, Ayolov insists on confronting its darker transformation. Play, he argues, has been instrumentalised, quantified, and weaponised. It has become compulsory rather than voluntary, continuous rather than episodic, and managerial rather than emancipatory. This inversion of the classical humanist account of play is the book’s defining provocation. The ludic, once a space of distance from seriousness, now organises seriousness itself.

The book’s opening foreword, titled “The Crying Game of Culture,” establishes the philosophical tone with remarkable clarity. Culture, Ayolov argues, is not a rational system governed by truth and calculation, but a symbolic game humans play together—often at great cost. The game is “crying” not because it is trivial, but because its stakes are real: life, dignity, sanity, and belonging. The danger arises when humans forget that culture is a game of their own making and begin to treat its rules as absolute reality. At that point, play freezes into religion, seriousness hardens into violence, and meaning demands sacrifice. This framing already signals that the book will resist both cynicism and optimism. It is neither a denunciation of culture nor a call to frivolity, but a demand for lucidity.

The conceptual backbone of the book is the progression from Homo Ludens to Homo Ludens 2.0 and finally Homo Ludens 2.1. This is not a technological determinist taxonomy, but a way of naming shifts in the relationship between play, tools, and social organisation. Homo Ludens 1.0 refers to play as embedded within ritual, art, law, and narrative—a bounded, symbolic activity that temporarily suspends ordinary life. Homo Ludens 2.0 marks the digital intensification of play: continuous engagement, quantified feedback, monetisation, and platform-based interaction. Homo Ludens 2.1 names the present condition, in which predictive systems, behavioural design, and immersive environments perforate the boundary between game and life altogether.

A key strength of the book lies in its refusal to treat technology as either neutral or omnipotent. Ayolov does not argue that digital tools “cause” panludism. Instead, he shows how technologies function as toy systems rather than survival systems. Their defining feature is not efficiency or necessity, but stimulation. Interfaces reward, rank, notify, nudge, and loop. Even domains traditionally associated with seriousness—education, health, productivity, politics—are redesigned as engagement machines. The result is a culture that promises improvement but delivers endless playability. Life is no longer oriented toward rest, completion, or meaning, but toward continuous participation.

The book advances four hypotheses that structure its argument and prevent it from dissolving into metaphor. The first hypothesis proposes that modern technology primarily functions as a toy system. The evidence for this is not drawn from entertainment alone, but from the redesign of supposedly serious tools into behavioural surfaces. The second hypothesis addresses gamification and its limits. Gamification, Ayolov argues, can increase participation but cannot generate ethical seriousness. Responsibility, truth, and community cannot be reduced to metrics, badges, or visibility. When everything is framed as a game, non-ludic categories such as duty, sacrifice, and refusal are displaced.

The third hypothesis concerns strategic play: the rise of game theory, simulation, and optimisation as the grammar of warfare, propaganda, and corporate power. Here the book is particularly incisive. Strategy promises mastery, but once it becomes totalising, it flattens moral life into outcomes and probabilities. War becomes a screen-based model; politics becomes a loyalty tournament; corporate power becomes an engagement farm. The paradox, Ayolov shows, is that strategy fails precisely when it claims mastery. When play is treated as a machine for guaranteed outcomes, it ceases to be play and becomes domination.

The fourth hypothesis articulates the central paradox of panludism: play only functions as play when it is not instrumentalised. The moment play is subordinated entirely to winning, optimisation, or extraction, it collapses into labour. This paradox explains why gamified life so often feels exhausting rather than joyful. People are invited to play, but stripped of the freedom to stop, lose, or refuse. They are not players but resources inside adaptive systems that learn, predict, and steer behaviour.

One of the book’s most compelling contributions is its analysis of exhaustion as a structural feature of panludism. In a culture of endless onboarding, quests, rankings, and feedback loops, depletion is reframed as a personal failure rather than a systemic outcome. The solution offered by the system is always more engagement. This insight connects the book to contemporary discussions of burnout, anxiety, and attention without reducing them to psychological pathology. Exhaustion is not accidental; it is the by-product of a culture that cannot stop playing.

Ayolov’s treatment of sport, madness, and playfulness further deepens the argument. Sport is analysed not as escapism but as a ritualised form of “self-elected madness,” a socially sanctioned suspension of rational priorities that paradoxically supports psychic balance. The psychoanalytic dimension of play is handled with care: play and madness are not opposites, but neighbouring states differentiated by containment and shared acknowledgement of illusion. Madness appears when symbolic scaffolding collapses; playfulness depends on knowing that the game is “just a game,” and committing to it nonetheless.

This analysis culminates in a striking claim: humans are not primarily rational animals who occasionally play, but playful animals who occasionally pretend to be rational. Large-scale social behaviour, the book argues, is driven less by calculation than by imitation, emotion, myth, ritual, and play. The belief that humans are fundamentally rational is revealed as a cultural aspiration rather than an empirical fact. This position does not reject reason; it relativises it within a broader anthropology of play.

The chapters on neoliberalism as a “universal playground” are among the book’s most original. Rather than treating neoliberalism as a coherent ideology, Ayolov describes it as a flexible rule-set capable of integrating radically different regimes. Neoliberalism functions like a global game board: it rewards accumulation, rent extraction, monopolisation, and strategic manipulation of constraints. Inequality is not a malfunction but the driving mechanic. The book’s use of the playground metaphor here is not decorative; it exposes how competition is naturalised while its rules remain opaque.

The conclusion, “Exit Without Winning,” is philosophically rigorous and ethically restrained. Ayolov explicitly refuses to offer strategies for “winning” the cultural game. Any such strategy, he argues, would reproduce the very logic under critique. Instead, the book proposes a criterion: whenever play is used to extract obedience, it ceases to be play; whenever play preserves the possibility of refusal, it becomes freedom. The most subversive act in a fully gamified culture is not to play harder, but to play lightly.

This insistence on exit rather than victory is one of the book’s most powerful gestures. Exit does not mean withdrawal from culture, but the preservation of distance. It means remembering that rules are human, victories provisional, and seriousness a role that can be exited. In this sense, the book is quietly ethical without being prescriptive. It does not demand a new ideology, but a recovered attitude.

Stylistically, The Ludicrous Culture is disciplined and coherent. The prose is essayistic rather than technical, but conceptually precise. The book resists jargon while introducing new terms where necessary. Its refusal to rely on extended case studies may frustrate some readers, but this restraint is consistent with its philosophical ambition. The book is diagnostic rather than programmatic.

In terms of intellectual positioning, the work stands at the intersection of philosophy of culture, media theory, psychoanalysis, and political economy, without being reducible to any one of these fields. It implicitly dialogues with traditions of critique without subordinating itself to them. Its originality lies not in novelty for its own sake, but in reassembling familiar insights into a new configuration that clarifies the present.

If there is a risk in the book, it lies in the radical nature of its diagnosis. By refusing solutions, the book demands a reader willing to sit with discomfort. Yet this refusal is also its integrity. In a culture obsessed with optimisation, the insistence that not everything should be solved is itself a form of resistance.

In sum, The Ludicrous Culture: Homo Ludens 2.1 is a serious and necessary book. It names a condition many experience but struggle to articulate. It does not ask readers to abandon play, but to rescue it—from compulsion, from extraction, and from false seriousness. Its final wisdom is austere and humane: no game is worth becoming real.

About the Creator

Peter Ayolov

Peter Ayolov’s key contribution to media theory is the development of the "Propaganda 2.0" or the "manufacture of dissent" model, which he details in his 2024 book, The Economic Policy of Online Media: Manufacture of Dissent.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.