The Return of the Thin White Mac: A Vigorous Defense of the Harddrive Full of Music

The MP3 and the Harddrive barely had their time in the spotlight. A forgotten format, that was never enough of a trend to have a comeback. But I believe they're the greatest format that ever existed, and may even have the power to save us from ourselves.

How are the format wars going this week? Well, streaming is down because of the whole Neil Young/Joni Mitchell thing, but it’s still massively dominant. The vinyl resurgence is hitting global supply chain hiccups. CDs are up, though it’s a testament to their decline that their rise may be down to one artist who old people can’t get enough of. And cassettes may be back, but it’s equally likely that some bored hipsters just convinced some naive journalists of a nonexistent trend. Join us next week when someone will be reporting that hampsterdance.com, and those cylinders that make mooing noises when you turn them upside down are the new preferred music formats.

The return of an old format is one of those hoary old journalistic cliches that seem to pop up at random. I’ve read at least three recently about the return of CDs, which argue persuasively that the shiny plastic discs were the apex of… something. I guess we’re at an age where the people who grew up with CDs are the ones writing nostalgia pieces.

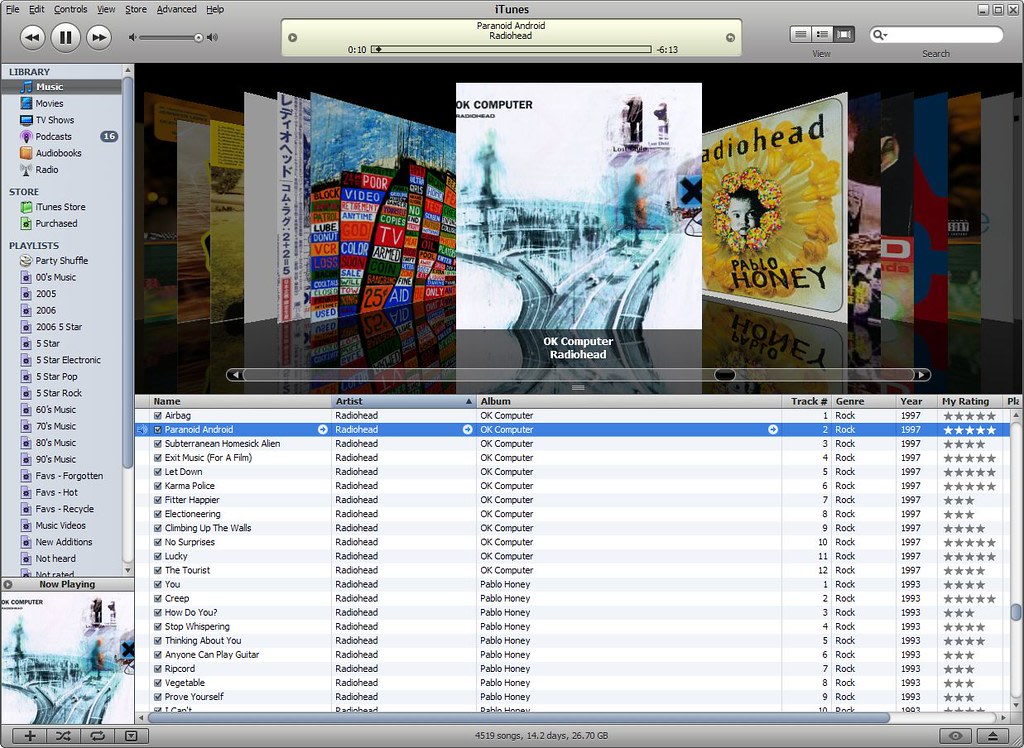

But there’s a format that I’ve never seen defended, and only rarely acknowledged: the harddrive full of MP3s. My 2008 Macbook Pro, with a 250GB harddrive contains around 2,100 albums. It lives on the bookshelf above the stereo, connected via aux cable. I own every one of those albums, they’re backed up on an external harddrive, in case the unthinkable happens. And I can easily find, and listen to any one of those albums any time I like.

I’ve been a late adopter my whole life. CDs have been around since the early 80s, but we were poor growing up; cassettes were the format of choice in our house. I was 16 in the year 2000, when I bought a CD player, and a handful of secondhand CDs with my first ever paycheck (They were Tuesday Night Music Club by Sheryl Crow, Automatic for the People by R.E.M., and the Lord of the Rings audiobook if you must know). A CD collection that had grown into the hundreds followed me throughout my itinerant 20s. I remember once moving apartments, but too poor to hire movers. Most of my possessions were jettisoned, but books, CDs, and a few items of clothing were moved by foot, in ten trips with a full hiking pack, of about a mile each.

I was aware that you could save music to your computer, and listen to it without the CD, but owning such a delicate, recalcitrant, and expensive piece of technology as a laptop seemed like such a hassle. I was even aware that there were MP3 players big enough to hold an entire CD collection, but not the ones I could afford. When I came across a Matt Groening cartoon of a tombstone that read “amassed a rather impressive CD collection” I had a panic attack and a printout of that cartoon accompanied my CD collection for the rest of its existence, tucked into a copy of the White Stripes’ White Blood Cells.

Esquire’s David Holmes referred to the years between 2003 and 2012 as the “deleted years”, lamenting that at the height of the MP3 era, music was disposable, and frequently got lost to data migration, planned obsolescence, or just the transience of digital data. But that simply was not my experience, every digital album that I have ever owned, CD or download, is on that Macbook, all the way back to Tuesday Night Music Club, and Automatic for the People. Of course, this is because of my own obsessiveness, and inability to ever delete any music ever. For the vast majority of people, Holmes’s point is salient; there is a decade of lost music. My point is just that it didn’t have to be that way, there’s no reason music saved to a harddrive has to be lost. With a portable harddrive, It’s almost exactly as durable as physical media, and a damn sight more convenient.

Its superiority over physical media is beyond argument. There’s just one format that one may argue has it beat. 2,100 albums taking up a space the size of a pack of cards? Try every album ever released ever, taking up no space at all. It’s easy to see why streaming took over so thoroughly, and so quickly. The arguments against streaming are more philosophical, and are less about objective measures like capacity and durability, but we’ve recently had a vivid demonstration of those arguments.

In response to Neil Young’s stand against Spotify for hosting the Joe Rogan podcast, Spotify released a statement containing the line: “We want all the world’s music and audio content to be available to Spotify users…” But they have to know that if this were ever possible, it’s getting less and less so. The trend in all streaming media is towards fragmentation, not consolidation. Just look at how the streaming wars have robbed the formerly dominant market leader, Netflix, of so much legacy content. Wanna watch Friends or The Office, you’ll need Peacock for that. Wanna watch any of the dozen or so Star Trek shows? They’re on CBS All Access. Rupaul’s Drag Race is on a service that someone just made up on the spot. Disney is gobbling up everything you love for Disney Plus. Having access to something is not the same as owning it. A future in which streaming is the music format du jour, is a world in which no one owns their favourite music.

You’re stranded on a desert island. What five albums are you desperately trying to build a portable cellular router out of coconuts, and pay $14.99 a month to hear?

Spotify, despite wanting to be the world’s go-to music repository, knows that market fragmentation is coming. That’s why they have pivoted to hosting podcasts, in much the same way Netflix tries to stem the tide of loss by plugging the gap with shows they’ve produced themselves. Wanna hear The Beatles’ White Album? Well you can't. But here’s some alt-right loser explaining why being allowed to say the N-word is essential for the future of space travel for four hours. It’ll be just as good, I promise.

But nothing will ever change the fact that I own the music on my harddrive, just like nothing will ever change the fact that I own the handful of CDs I kept for sentimental reasons, or my modest vinyl collection.

And I am not facing the ethical dilemma of supporting the platform that would pay upwards of 100 million dollars for Joe Rogan’s nonsense. This is a bigger factor than just one bad decision by Spotify, or one problematic service, or the loss of access to a few artists who you probably didn’t listen to much anyway. Existing in a late capitalist world means relying on, and interacting with, corporations constantly. Our reliance, and the deep reach of those corporations, make boycotts untenable, logistically impossible, and frequently pointless. Say the Joe Rogan issue prompted you to ditch Spotify, where are you going to go? Sure, there are plenty of options (capitalism is good at giving us choice), but you’re taking an awfully big bet that Apple Music, or Tidal will never do anything as problematic.

On the other hand, while it would be naive to insist that my harddrive did not require the involvement of evil corporations, I paid off my Macbook a decade ago, and the external harddrive cost just over $100. If I never pay another cent to a multinational corporation for my music, I’ll still have all the same music. This is as close as one gets to cutting the cord with late capitalism.

Music, stories, and art are intrinsic to the human experience. They are literally among the defining aspects of human culture. We already restrict creating music and stories to those who are deemed “talented” by capitalism’s warped standards of talent. The less we place capitalism in the position of gatekeeper, mediating our access to the things that make us human, the better.

About the Creator

Michael Atkins-Prescott

Non-binary artist, DJ writer, bird fancier and licensed forklift driver.

I'm in New Zealand, with my wife and a cat, a pretty decent kitchen,and a turntable I fixed myself.

pssstt... https://linktr.ee/michaelatkinsprescott

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.